Visual Arts Feature: Lining It Up — Dance/Draw at the ICA

“Dance/Draw” at the ICA is a major exhibit about how moving bodies leave traces, what curator Helen Molesworth, not particularly originally, calls the “afterlife of dance.” To a lesser extent, it’s also about how visual artists think about motion when they’re not focused on particular bodies.

By Debra Cash

ICA Curator Helen Molesworth — She learned that dance is an embodied practice that carries sensations between people.

Helen Molesworth likes to tell the story of the first time she saw a drawing by American, postmodern choreographer Trisha Brown. A series of wide arcs and blurry geometries, the drawing consisted of the traces Brown had left on a sheet of paper as she rolled over the floor with charcoal pastel at her back and clutched between her toes. Brown had been drawing since the early 1970s, and her works were of a piece with not only her own choreographic experiments—walking up the walls of the Whitney museum, signaling over Manhattan rooftops, erasing the locations of dancers in a cloud of steam—but also of the visual artists, especially her pal Robert Rauschenberg, who were her regular collaborators.

Still, in 2009 what struck Molesworth as a revelation was how she experienced the drawings as an observer. They made her want to move, to try to recreate the making of the drawings in her own body. This was news.

In the catalog for the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston’s (ICA’s) major new exhibit, Dance/Draw, on view through January 16, 2012, Molesworth attributes her newly embodied awareness to having recently taken up a yoga practice. I don’t know if Molesworth found herself physically moving her hands as if to paint, or crochet, or make architectural models when faced with other art works during that period of changed awareness, but she was learning what almost all dancers, and many audiences, already know. Dance is an embodied practice that carries sensations between people. Dance communicates viscerally. If you must, blame the mirror neurons. What’s interesting is that Molesworth came to this understanding when the dance came to her on her art historian turf, as marks on paper, action on the two-dimensional page.

Dance/Draw is framed as an exhibition about the intersection of two forms of art, dancing and drawing. Grandly, it is situated in the context of an entire series of activities, from conversations and collaborations between visual artists and dancers to a mini-festival of dance-themed animation and performances presented in the galleries during regular museum hours and special, evening dance concerts. Happily, this includes a retrospective by Trisha Brown that is the first time her company has appeared in Boston in a decade.

I’ll be writing about many of these events during the coming weeks, but it’s important to start with what this exhibit is not. It is not a historical survey of how dance and the visual arts have influenced each other (think Sergei Diaghilev and Leon Bakst, Martha Graham and Isamu Noguchi, Merce Cunningham and Jasper Johns). It is not fundamentally a show of artists who have taken dance, or the moving human figure, as their subject matter (think Abraham Walkowitz drawing Isadora Duncan or the flying, falling figures by Jonathan Borofsky now hung like Christmas ornaments, or maybe piñatas, above the corridors of the Museum of Fine Arts’s new Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art).

No, Dance/Draw is about how moving bodies leave traces, what Molesworth, not particularly originally, calls the “afterlife of dance.” To a lesser extent, it’s also about how visual artists think about motion when they’re not focused on particular bodies.

The exhibition unfolds as an ingenious palindrome with the first and last galleries reprising similar images into refreshed questions. “More Than Just The Hand” in the first gallery showcases images where the body has “created” a persistent visual image. We meet Trisha Brown’s drawings alongside a video of Janine Antoni dragging her hair across the floor in overlapping swirls of dye and a stick-scattered “painting” she made by coating her eyelashes with Maybelline and fluttering them against the paper. (One shudders to think how archivists of the future will conserve something painted with CoverGirl Thick Lash.)

These are deliberate “drawings” no matter how serendipitous the final image turns out to be. I much preferred Daniel Ranalli’s wonderful diptych of a bunch of snails set up in a spiral (a miniaturized, art-world joke at the expense of Robert Smithson’s monumental Spiral Jetty and the whole Earthworks crowd) who, in the next frame, have scattered, leaving ridges behind them to proclaim their paths to freedom. And John Cage’s 1965 edible seaweed drawing? Well, I guess seeing, touching, and tasting tick through three of the embodied senses, but one imagines that it’s here because Molesworth has gotten caught up in her idea that a non-drawn drawing is something to see, and who can curate an avant-garde show without John’s merry spirit presiding?

“The Line” opens with Ruth Asawa’s extraordinary, nested bulbs of crocheted, copper wire. They look good in the white space and even better in a current magazine spread showing them hanging in Ellen and Portia’s living room. Crochet, knitting, and all types of sewing have, of course, been traditionally gendered crafts, and the dancing is here, to stretch a point, in the physical act of making. Molesworth tries to make a case for the “embodied” ways that sagging lines in works like Eva Hesse’s and Howardena Pindell’s re-enact the force of gravity on the human body, but I don’t buy it any more than I buy that Fred Sandback’s taut yarn “drawings” are, as Molesworth says, “a dance floor you dance on.”

Which brings us to dependencies of which I doubt she’s even aware. The section of Dance/Draw labeled simply “Dancing” is dominated by a film of Yvonne Rainer dancing her solo “Trio A,” in a grainy, 1978 documentation. (The same film was a centerpiece of the Carpenter Center’s 2005 Rainer retrospective.) This landmark piece, with its deliberately uninflected gestures and resistance to any portrayal of spectacle, would have made her famous even if she hadn’t gone on to become an avant-garde filmmaker and activist.

But Rainer, and her colleagues at the Judson Dance Theatre in the early 60s, came from somewhere. I don’t think you can understand why Judson mattered without knowing how Merce Cunningham swerved from the modern dance that preceded it, and I don’t think you can address the “anything can be dance if you attend to it” ethic that inspired Brown to set up a web of bright t-shirts for dancers to crawl over and through without knowing more about Happenings and the rapscallion conceptualists of Fluxus. Molesworth knows about them, of course; she is a smart, thorough, and learned person. But in this thematically organized show, when history is traded for theory, history always gets the short end of the charcoal stick.

Most troubling, Molesworth is more attuned to what these dance artists wrote about their work than what it looks like or even how it might have been or still could be experienced. One of the reasons that an artist like Rainer has come to dominate the art-historical world’s appreciation of Judson is that she said so much about it, and because her ideas were certified in the congruent fields of film studies and feminist critique. This is not to denigrate Rainer, far from it. But glib theory, not artistic expression, is what makes a dancer like Rashaad Newsome’s glossy video on the opposite wall seem to be significant when all it is, really, is a bunch of voguing attitude by a good-looking performer.

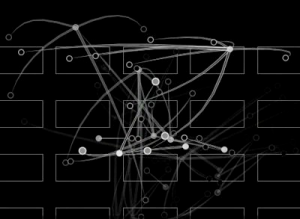

That’s why the inclusion of dance films created by the dancers themselves matter. When William Forsythe offers his “Improvisation Technologies” as a video textbook to his movement ideas or Bill T. Jones dances in a 3-D reinterpretation of the landmark, motion capture video “Ghostcatching” made by the OpenEnded Group (and be sure to get your 3-D glasses to get the full effect of this wonderful piece), what they tell can be affirmed by what they actually show.

When finally “Drawing” comes around again to close the exhibit, it has re-juggled the foreground so that Helen Almeida’s photographs, where the artist includes her presence as an element of a conventional drawing, seems tame, while Tracey Emin’s disembodied, neon legs with their little loop of a vulva read as a witty commercial come-on. Afterwards, you can wander into the harbor-side walkway and refresh your eyes with nature’s color—this is an awfully black-and-white show—or duck into the ICA’s Poss Family Mediatheque where the staff has assembled a bunch of dance materials I haven’t yet had time to explore. But above the stepped down chute to the water is a sculpture that Cecilia Vicuna calls “Water Weaving,” a white textile “drawing” that drapes over the computer monitors like a canopy and matches the undulations of the waves below. If it feels like dancing to be there, it’s not because you’re entering “an unwitting stage.” It’s because you’re breathing again.

Debra Cash, Executive Director of Boston Dance Alliance, www.bostondancealliance.org, is a founding Senior Contributor to The Arts Fuse and a member of its Board of Directors. In 2017 she was honored as Champion of the Arts by OrigiNation Cultural Arts Center.

C 2011 Debra Cash