Poetry Review: A Playful Walk along “The Illustrated Edge”

In locales as varied as Israel, Kenya, Massachusetts, and the country of the brain, and in rough groupings of poems about small daily epiphanies, relationships, loss and death, and the sad affairs of the world, the poems in The Illustrated Edge explore the meandering paths of all sorts and mixtures of feelings.

The Illustrated Edge by Marsha Pomerantz. Biblioasis, 86 pages, $15.95.

By Maryann Corbett

The back-cover blurbs for Marsha Pomerantz’s The Illustrated Edge puzzle me a little. “Jangling, jumbled syntax….” says one, and the other says, “. . . deferring ordinary syntax.” Perhaps on the whole those statements attract the readers who can best enjoy the tougher poems in this book, but they’re not quite accurate. The book is not as difficult as all that. It’s much more inviting, and it’s much more various.

Permit me a language-nerd moment: The syntax of the poems is not what’s striking. The poems proceed in normal, English word order, with articles in front of nouns and subjects ahead of predicates. The reassuringly standard syntax, in fact, is what lets the reader get a purchase on the poems in spite of the elements that do look odd at times: the semantics, the unexpected juxtapositions of words and ideas, the imaginative leaps that can look like incoherence until one sees how to read them, and the inventive use of space on the page.

So what about the semantics? A lot of attention has already been directed at the poem “To My Translator,” which was both featured on Verse Daily and discussed by Daniel Bosch in Boston Review. I’m not certain it’s any more strange semantically than other poems in the collection. But it does more consciously focus on its own strangeness. It does so not only by its title but by aping the not-quite-idiomatic phrasing that shows up in Babelfish, Google Translate, or badly done user manuals. A translator herself, Pomerantz has a feel for all the pitfalls, and she uses translationese as a way into layered meaning.

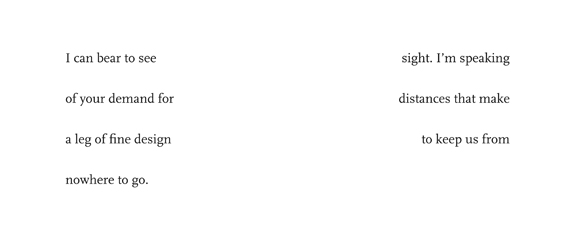

All the poems are this inventive but not in this same way. Where they’re tough to crack, their toughness comes not only from abandoning idiom but from what looks like failure to cohere. For example, here’s an excerpt from the final segment of “Rib|Cage”:

(In case this doesn’t successfully format on the screen, I’ll note that on the page, the lines are right and left justified, with a big open space in the center.) The content and the shape of the poem are conversing with each other and with the shapes and meanings in the first three sections of the poem. That much is discernible. What’s more difficult is deciding what, or how many subjects, the poem is about.

Another poem that violates our expectations of “aboutness” is the book’s title poem, the last in the collection. It’s a cross between meditative content and the format of technical-manual-with-exploded-diagrams. Here’s its third paragraph:

Sometimes an edge takes to a table, in which case there are

drips and crumbs and bellies pressed up close. Digestion is heard,

also hunger (fig. 3), sometimes bookish crinkly thoughts, usually

black on a cream ground, a smoothness pressed into texture.

Elbows attend, indecisive, poise-or-plunge.

The poem needs to be seen whole to come into focus as a study of edginess, or uneasiness, or the qualm-ridden moments and decades of life.

About poems like these three, the blurbs are right: they “demand and reward rereading.” But most of the book’s poems come open more easily than these. Many of them show a similar fondness for forms and patterns lifted from daily life and the other arts. But they also have plenty of the coherence and familiarity that gives readers a handle to grab. “How to Love,” for example, is a wedding poem, as shown by its dedication. It’s constructed entirely in the language of tempo markings on musical scores, Italian and German, and it ends on the hopeful note of all epithalamia, in drawn-out final measures, “Sostenuto. Sostenuto. Sostenuto.” (I feel fairly certain that the bride and groom were musicians. Classical music features in the working background of several other poems as well.) As another example, “What Birds Mean When They Say That” riffs on the terminology of birdsong recognition. There are cookbook tables; there are conversational formulae; there are Chinese painting inscriptions; there is government regulationese.

There is also pure descriptive simplicity, plain and accessible, as in “Tortoise Shell on a Windowsill”:

The inhabitant is out, apparently

gouged. Now we can study pure

shelter. Waxy chitin, regular ridges

brown-and-yellow fields pressing past

their boundaries on a hillside. Arching

horn inspired Song ceramics and later

eyeglass frames looking little like

this helmet for the heart and gut

that a laggard engineered to surmount

himself….

Or again, in “Tree”:

All morning I watched through my window the fleshy maple

felled. That had twitched and shaded in the wind and played

its moving parts against a still, joined earth. The sawman in his

metal pulpit, inching upwards against the trunk, making ovals

empty, spot by spot, till even space fell down and bounced

once….

Usually, though, the pure lyric methods are working in counterpoint with some other element. Often it’s something typographical or layout based, something entirely on the page. And such elements confirm me in my belief that some poems just don’t do stage, or even mp3 file, very well—that the page, the screen, the visual element in our intake of poetry remains essential, no matter what the slammers and performance mavens declare.

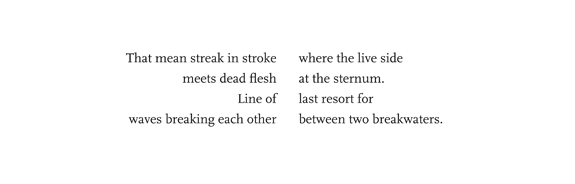

Without seeing the page, how would we perceive that “Tri-Town Paving Does a Country Road to the Strains of Bach’s B Minor Mass” is in the shape of a road stripe? That “Winding Sheet” is in the shape of the attic stairs the narrator has climbed? That in “Aunt Jessie Eats,” the four small, supplementary poems go around the central poem like the points of a pinwheel? What could the voice do with the on-page arrangement of “Rib|Cage,” which is set up in table form, each line in two half-lines like Old English alliterative verse but boxed, like the layout of a spreadsheet program? Besides these special formats, the book uses a great deal of indent-pattern and stanza-shape variety for its own sake, just for fun.

Pomerantz also has a lot of fun with sound, as in her opening poem, “The Illustrated Middle.” It’s a study of liminal states, not-quite-this-or-that, in which all the half-lines hang off a spine of caesurae:

Assonance, alliteration, internal rhyme, onomatopoeia, punning are all there in these poems.

One thing that’s not here, though, and a thing I miss, is a sense of the line and the strophe as units of sound. Again, I’m going to argue a bit with the blurb language, which mentions “formal exuberance.” That’s a phrase that might mislead some people into expecting meter or received forms. Those aren’t here in the standard sense, exuberant though the poet is about playing with patterns. Line breaks in these poems come in mid-phrase and in mid-word, between articles and nouns, and at spots where the voice can’t possibly break, as if the line meant nothing vocally. I have to assume that for Pomerantz it doesn’t, and the presence of so many charmingly eye-driven poems supports my view. I looked for hints of meter; they’re faint if they’re there. The feeling of speech rhythm is strongest in the prose poems and the long-liners, where no page-design goals interfere with the flow of the sound.

One more lack I feel is of emotional definiteness. I wish there were more poems like “How to Love,” “Aunt Jessie Eats,” and “Tree,” in which it’s clear that there’s one way to feel about the situation in the poem. But I might simply be wrong to wish for that. The indefinite, the uncertain, the mixed, the wavering emotion, is probably more normative for 21st-century life than the clear one, which may be why Pomerantz traverses so many such emotions. In locales as varied as Israel, Kenya, Massachusetts, and the country of the brain, and in rough groupings of poems about small daily epiphanies, relationships, loss and death, and the sad affairs of the world, she explores the meandering paths of all sorts and mixtures of feelings.

I hope that the book designers had as much fun on these paths as the poet; it certainly looks as though they did. The matte, textured stock of the cover, the distinctive flaps and endpapers, the understated photo, the laid paper of the pages, the different uses of leading to provide breathing space suited to the needs of the text—it’s all sighingly lovely, an object inspiring us to value beautiful pages and to lament the many offenses against good typography all around us. Given the special challenges of poems with boxed table formats, centered spines, and bits scattered all over a page, Biblioasis and its book design staff deserve their own mention and praise.

“Having fun” and “enjoying challenge” and “exploring possibilities” are good summings-up of this book, both in form and content. The back-cover blurbs make much of the words “inventive” and “playfulness” and “play.” And in those particulars, they’ve got it right.

Marsha Pomerantz will read from The Illustrated Edge at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education, Cambridge, MA, as part of the Blacksmith House Poetry Series on October 31 at 8 p.m.