Film Review: Take a “Drive,” She Says

In Drive director Nicolas Winding Refn crafts a cool, tight, and stylish film that gets away with a lot. He managed to make a movie that works as some kind of bizarre but wonderful Michael Mann/Jean-Pierre Melville/Quentin Tarantino mash-up, helmed by star Ryan Gosling, who described it as a “violent John Hughes movie.”

Drive. Directed by Nicholas Winding Refn. At Boston’s AMC Loews Common 19 other theaters throughout New England.

By Maraithe Thomas

I’m going to begin this review of Drive, as did the movie itself, with the opening credits. This is the only movie I’ve ever seen in a theater where the audience laughed, collectively, at the first words that appeared on the screen. What the words said, if it was the name of the studio or the production company or whatever else, didn’t matter. They were laughing at the typeface.

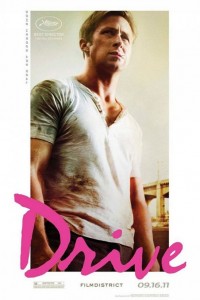

If you’ve heard of this movie, you’ve probably already seen the neon pink, throwback font on posters and in the trailer, but seeing it shown with synthetic pop music under aerial shots of Los Angeles leaves so much more to wonder about. It seems ill-fitting, like the font you pick as a joke before settling on the real one. But that initial feeling conjured by such a stylistic collision ends up setting the tone for the entire movie, because it is one of Drive’s great tricks.

The film, adapted from a novel by James Sillis, stars Ryan Gosling (who deserves, but probably won’t get, an Oscar for this) as a stunt car driver by day, sometimes getaway driver by night. He has no name (he’s credited as “The Driver”), no history, and no family that we know of. He doesn’t say much at all, but his actions—and his driving—ground him firmly onscreen.

In one of the opening scenes, Gosling helps two guys pull off a robbery in downtown LA. Like The Driver, we don’t know what they’re robbing or who from. He doesn’t want to know or do anything but drive. The burglars jump safely back in the car with their loot, but the police are already onto them. The Driver doesn’t break a sweat; on the contrary, he’s thrilled. With his police scanner as a guide, he weaves smartly down city streets and under tunnels. At one point, he drives right behind a police officer for a good thousand feet. The cinematography in this scene is superb; the camera never leaves the car, but it manages to be a tight, sleek, and to-the-point chase. The Driver gets the two to safety by parking in the crowded garage of an NBA arena. Leaving them in the car, he puts on his baseball cap and walks out—cool as can be. His charisma is off the charts, and we can’t help but feel like we’re in good hands.

The Driver lives this way, an existential isolate, until he meets his neighbor Irene, played by the adorable Carey Mulligan, and her young son Benicio. They spend a lot of time together acting like a happy family and growing close, though both are shy, until one day Irene announces her husband is coming home from jail in a week.

The return of her husband, Standard (not the deluxe version, as Irene later jokes), is complicated by the fact that he’s actually a pretty solid guy. The Driver continues to spend time with the family for dinner and other things, which allows him to find out that Standard owes some guys a lot of money. To pay his debt, he has to do one last job: a heist at a local pawn shop. When it becomes clear that Irene and Benicio’s lives are in danger, The Driver steps in, ever the hero, to help the family out. But things go awry, as they tend to do in movies when it’s that “one last job.” Our hero travels deeper and deeper down the hole that Standard had dug for himself, breaking his rule about not wanting to know about the crimes he helps thieves get away from, at great personal risk and little personal gain.

Nicolas Winding Refn (The Pusher Trilogy, Bronson, Valhalla Rising), who picked up the top directing award at Cannes this year, crafts a cool, tight, and stylish film that gets away with a lot. He managed to make a movie that works as some kind of bizarre but wonderful Michael Mann/Jean-Pierre Melville/Quentin Tarantino mash-up, helmed by Gosling, who described it as a “violent John Hughes movie.” In this film, an angsty romance scenes coexist alongside scenes of extreme and shocking violence, but the clash comes off as more laughable than horrifying. You’ll gasp and then giggle.

The occasional gore isn’t necessarily worse than, say, your average Tarantino film, but combined with Gosling’s reserved nature, the slow, Melville-esque cinematography that builds up to the second half, each bout of violence is like jumping into an ice bath. The violence is the extreme version of using a girly, pink font for an action movie. We just can’t believe our good guy Gosling just brutally stabbed some guy with a window shard. (But he did!)

The film isn’t without flaws, minor as they may be. The plot gets a little confusing after it goes deeper into the heist and its aftermath. We also wonder at times why Gosling’s character risks his entire heretofore contented life for a woman he’s only recently met. It’s entirely selfless, and by the end there’s really nothing left in it for him. Refn says he wanted The Driver to be like a character from a fairy tale, and though it doesn’t end like one, the whole thing works much better if you can forget reason, realism, and logic and just cruise down Refn’s super-charged highway.