Book Commentary: The Emperor of Lies = The Emperor’s New Clothes?

Should we fictionalize the Holocaust? This is not only a literary question, but a moral one as well, issues raised by the publication of the translation of The Emperor of Lies, a novel about the ways in which the Jews in the Lodz ghetto struggled to survive the Nazis.

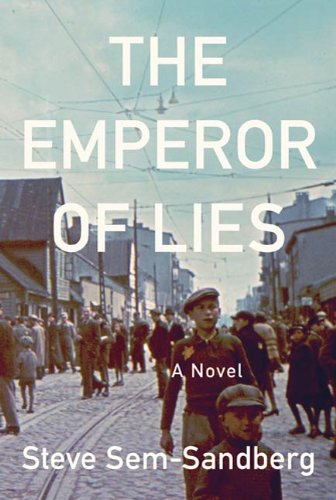

The Emperor of Lies by Steve Sem-Sandberg. Translated from the Swedish by Sarah Death. Farrar Straus & Giroux, 664 pages, $30.

By Roberta Silman

First, these are the facts: Steve Sem-Sandberg, a Swedish writer born in 1958, has written a new Holocaust novel, published in Swedish as The Destitutes of Lodz and now translated into English by the appropriately named Sarah Death to The Emperor of Lies. Unlike several earlier books by Sem-Sandberg that had science fiction and holocaust themes (a trilogy set in Ravensbrueck), this novel has become a best-seller in Sweden, selling 370,000 copies, has been sold in other countries, including ours, and has just won a prize equivalent to the Man Booker Prize in England. This is clearly his “breakthrough” novel, and the truth is that Sem-Sandberg can write, as attested to by glowing blurbs for the book from Hilary Mantel and Sebastian Barry.

But about a third of the way through this book I found myself getting very angry. First of all, I had read most of this before in fictionalized form in 1979 when Leslie Epstein published The King of the Jews, which ran into the same kind of criticism I have for this more recent rendering. Both Epstein and Sem-Sandberg relied on detailed historical material from the Lodz ghetto (sealed in 1940 and renamed the Littmannsdadt Ghetto) in which about 200,000 Jews slaved in factories in return for food, where 50,000 died, and where the rest were sent to camps like Chelmno and Auschwitz. The protagonist for both of these novels (one can hardly use the word, hero) is Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the lunatic or monster—depending on how you regard him—who created the “best work camp for the Nazis” and who, some believe, actually thought he might save those in his ghetto at the end of the war. He was wrong and died in Auschwitz in 1945.

But why write a novel about a historical character whose life is well documented? Recreating a man who has been called “a monster of evil” is not really an act of the imagination, and it brings nothing new to the subject that has been explored by witnesses in the camps or ghettoes who have actually experienced fear and hiding—writers like Primo Levi or H. G. Adler or Aharon Appelfeld or Saul Friedlander or Victor Klemperer. There is a part of me that feels that Epstein and Sem-Sandberg are simply dancing on the graves of those who have died, feeding their impoverished imaginations with material that doesn’t really belong to them. And that, in writing this about this man, they have revealed an almost sadistic side of themselves. While it is so important that we constantly bear witness to the horrors of the holocaust, I am not sure that books like this are as useful as ones written by ones by people who actually experienced it.

Trying to calm myself down, I went online to some of the reviews that have already been printed and found an excellent one by Simon Schama for the Financial Times, which basically has the same point of view as mine. He points out, rightly, that Sem-Sandberg gives the reader a good sense of place, a variety of characters in this microcosm of the human condition, even some humor. But there is also a lot of torture and disgusting descriptions of those acts. Schama says, “You want to ask the writer: did writing that particular sentence, that particular simile, give you special satisfaction?” I totally agree and, moreover, can hardly recommend to readers in their right minds the experience of reading such stuff. What occurred to me as I read was that by engaging in the very act of reading, I was becoming a participant in this story and that, by so doing, I was actually betraying Rumkowski’s victims whom Sem-Sandberg has attempted to bring to life.

There are also other reviews, like Carmen Callil’s in The Manchester Guardian, that treat this novel like something that might have been written by Balzac or Dickens or even our own Faulkner because it doesn’t flinch from revealing the human condition with all its flaws. Callil is an eminent author and publisher who was one of the founders of Virago Press and recently caused a flap after she resigned from the judging committee of the Man Booker Prize in England when her colleagues decided to award it to Philip Roth. But doesn’t she realize that the Lodz ghetto is not the Marshalsea Prison of Little Dorrit or the law courts of the merciless and endless case of Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce in Bleak House? Or the French countryside or an imaginary figment of the American South? The Lodz Ghetto was a holding pen for people who were condemned to death because of no other reason than they were born Jews.

Steve Sem-Sandberg: Swedes should be ashamed of propelling the author of THE EMPEROR OF LIES into the public eye.

There is no narrative here. They were condemned to death when they arrived, and they are condemned to death when they leave. And although they are part of the community that Sem-Sandberg has fictionalized, they are “underdeveloped” characters speaking “wooden and unconvincing” dialogue (at least our own Publishers Weekly got it right) whose fate is obscenely ghoulish. When I read the last sentence of Callil’s review, “Dickens would like this novel,” I was appalled by her lack of insight. She is not the only reviewer who has compared this book to Dickens. Are we all losing our minds?

So, instead of telling you any more about this novel, which will probably receive its share of thoughtful reviews and good publicity, I would like readers to ponder Schama’s very relevant question: Should we fictionalize the Holocaust? This is not only a literary question but a moral one as well. I can imagine novels published now and in the future where the Holocaust plays a part in the molding of character and has their place in the collective memory. I can also recommend novels that have shaped the darkness of our human condition into something of lasting value, as Kafka did, with an uncanny prescience before the Holocaust occurred.

But this book, with its pompous presentation of maps, a glossary, a list of the main characters (as if we were to immerse ourselves in Tolstoy), is in Schama’s words, “just a 664 page footnote” to the historical material that abounds. Instead of reading this disturbing, often repulsive, new novel, you would be better off making a trip to the Holocaust Museum or Yad Vashem or reading straight history or going back to the authors mentioned above. And as for the 370,000 Swedes who have propelled Sem-Sandberg into the public eye, shame on them.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net

It’s not often I think of business terms in regard to literature but I do here. What is the “value added” that the novelist contributes not only to this historical material but to all historical material? In some cases, the value added is enormous, opening a way for the reader to enter previously unknown territory. It sounds like Sem-Sanberg adds little.

I have felt strongly for many years that certain aspects of the experience encompassed by the term “Holocaust” should be off limits in fiction to anyone who wasn’t there as a witness. I appreciate what Aharon Appelfeld has done — created a world of before and after, never stepping into the camps and describing what occurred there. Other writers I respect have fought, and partially lost, the temptation to write about what happened in the camps.

The historical record is available — why play with the facts?

I agree with every word in Roberta’s review, and I appreciate having access to Simon Schama’s review, which is also right on the money. I am deeply disappointed that a writer of the stature of Sebastian Barry helped promote this novel, which, according to Roberta betrays the victims by cheapening their experiences.

The idea that the Holocaust should not be fictionalized lacks common sense. Even when one is reading a memoir by someone who lived through the Holocaust one is really imagining the experience that the person is describing as majority of the people on this planet have not lived through a holocaust of their own and cannot really know the experience. All non-fiction reading requires the reader to imagine the events and circumstances as the reader was not present when they unfolded.

If you get a few people who have read the same non-fiction book to discuss that book or one event within it…you don’t end up with just one interpretation but several interpretations even though only one event may have actually taken place. Interpretation of any real situation or event fictionalises the situation or the event to a certain extent…it is next to impossible not to lend human imagination even to non-fiction. So why say that certain historical tragedies, such as the Holocaust, should be off limits to writers of fiction.

Although I am inclined to agree with much of your commentary regarding The Emperor of Lies, I find the last sentence of your review rather puzzling: “And as for the 370,000 Swedes who have propelled Sem-Sandberg into the public eye, shame on them.”

It would seem to me that the 370,000 Swedes who purchased TEL are guilty of little more than being conned into the purchase of a bad book doubtlessly hyped by its publisher. In an era when memes “go viral” with astonishing speed–and almost anything can easily be monetized with “one click” online purchases–it is hardly surprising that the book sold so well. Then, too, you read it: did you borrow a copy ? or do you have reason to be ashamed also?