Book Review: A Memoir That Gives Solace to Us All

A best seller in France, Emmanuel Carrère’s quirky but ultimately compelling memoir examines the effects of two disasters on very separate groups of people to whom the writer is connected, at the beginning, quite peripherally.

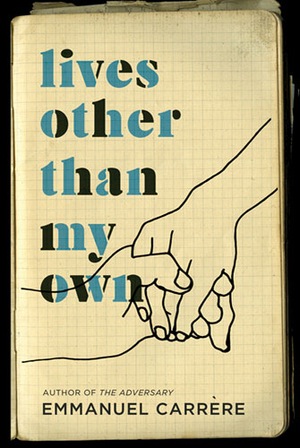

Lives Other Than My Own by Emmanuel Carrère. Translated from the French by Linda Coverdale. Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Co., 256 pages. $26.

By Roberta Silman

Like all books that pretend to be about other people, Carrère’s memoir turns out to be about him as much as the story he thinks he is telling. In this quirky but ultimately compelling book, he examines the effects of two disasters on very separate groups of people to whom he is connected, at the beginning, quite peripherally.

Although Carrère writes well and has been lucky enough to have Linda Coverdale as his translator for this best seller in France, and although he clearly has a good sense of himself (a previous memoir was entitled My Life As a Russian Novel), this new memoir begins with a strange cluelessness. It’s as if he is just now discovering what is truly important in life, which seems a bit late for someone already well into his 50s. It seems only fair, though, to confess that my high standard for memoirs is Vladimir Nabokov’s masterpiece Speak Memory, which is shaped like a piece of fiction and has an artistic logic that few memoirists have been able to achieve.

The logic that gives shape to Carrère’s memoir is that he, a writer of both fiction and non-fiction, and his journalist wife, Helene, although on vacation in Sri Lanka in 2004 with their respective sons from first marriages, are on the brink of separating. Why is not very clear and seems to be that nameless ennui that attacks many couples and which I will never understand, having been in a long marriage since my early 20s and having learned early that marriage, like most conventions in a civilized society, has ebbs and flows, good patches and narrow ones.

Into this boring predicament comes, without warning, of course, a disaster of epic proportions, the tsunami of 2004 we all remember as the worst one until the recent devastation in Japan. It sweeps away four-year-old Juliette while her parents have gone on an errand and she is being watched by her grandfather, Carrère’s friend.

The ensuing grief of Juliette’s parents and grandfather is recorded in meticulous detail, alongside Carrère’s slow but persistent awakening to his own wife’s strength and intelligence. As Helene comes alive and reaches out to help others in surprising ways, the book itself comes alive, and you begin to read with more urgency, especially after they meet a Scottish woman named Ruth who was on her honeymoon and is now frantic because she has been separated from her new husband. By the time they have to return to their home in Paris, all talk of separating has stopped, and Helene and Carrère have more or less promised each other that they will stay together, at least for now.

Soon after their return, however, they are faced with another disaster. Helene’s sister, whom Carrère really doesn’t know very well and also named Juliette, was a childhood cancer victim and amputee when a teenager. Now, after being hospitalized for an embolism, she is told that she has had has a recurrence of cancer (this time in the breast and lungs) and is terminally ill. This Juliette has been fortunate enough to have had a wonderful marriage and three young daughters as well as an interesting job as a judge in a French court where she has a long-lasting and very important relationship with a colleague, also an amputee, named Etienne.

In this section, there are also surprises, and we see Carrère’s rather self-centered mind literally expanding to understand the nature of relationships very different from those he has known—the unconditional love of two people, Juliette and Patrice, in a somewhat unlikely marriage and the unconditional love that can develop between a man and a woman, Juliette and Etienne, who work together and who share so much intellectually. These two were referred to as “the judge in Vienne.”

French author Emmanuel Carrère — in this book, his rather self-centered mind expands to understand the nature of relationships different from those he has known.

Here is Carrère describing their initial affinity:

They had recognized each other. They’d known the same suffering. . . They came from the same world. . .Their marriages were the heart of their lives, the key to their accomplishments.

Yet their bond grew into something Etienne described as “carnal and voluptuous in the way they practiced law together.” Something almost indescribable, without any sexual connotation, but something very rare, which their partners made peace with and which nurtured them and also furthered the cause of justice in this small part of France. Since most of their cases had to do with the debt of ordinary citizens against the large credit card companies, there is an almost Dickensian tinge to some of the descriptions and how their ideas—Juliette’s more to the right and Etienne’s more to the left—meshed and gave them so much pleasure and fulfillment professionally.

Etienne’s back story fascinates Carrère, and he and Juliette’s friend become close, as Etienne tells the author about his life up to this time. As we learn more about Etienne, we feel the book opening up, witness Carrère realizing how much more to life there really is than he previously knew. We see him acknowledging his own ambition and delusions (when Juliette takes ill, a film of his is being shown at Cannes, and he revels in all the glory, but with a glimmer of self-awareness), and we begin to root for him and Helene as we share their grief over Juliette’s illness and the sorrow of Patrice and their daughters. Carrère handles time well, and as he moves back and forth in it, the prose becomes more and more assured.

When he tells us about Patrice describing the last moments of Juliette’s life, the language reflects his own acceptance of the strange mysteries that abound in ordinary life:

I was relieved that everything was over but above all, at that moment I felt immense affection for Juliette. I don’t know how to put this; affection seems like a feeble word, but I felt something greater and stronger than love. A few hours later, at the hospital, funeral parlor, the feeling had already changed. Love, yes, but that vast affection, it was gone.

Indeed, by the time this book draws to a close, we have been enriched by Carrère’s ability to make us feel how precious—actually sacred might be a better word—the love that filled Juliette’s life truly was. And still is. And, as Carrère’s life with Helene achieves its own fulfillment, I thought of Nabokov’s mother’s motto—“To love with all your heart and leave the rest to fate.” In his last pages, Carrère conveys, in clear and moving prose, the healing that has taken place after these two catastrophes; in so doing, he stretches his hand across time and space to give solace to us all.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net

Tagged: Emmanuel Carrère, french, Linda Coverdale, Lives Other Than My Own, memoir, My Life As a Russian Novel, The Adversary, The Mustache