Culture Vulture: Reading Jung’s “Red Book,” Conclusion

Whether you’re a Jungian or a Freudian, think Jung was a genius or charlatan, or even if you’re someone who’s never given much thought to psychotherapy, the exhibition on the “The Red Book” at New York City’s Rubin Museum of Art (which runs through February 15) is worth a visit.

THE RED BOOK by C.G. Jung. Edited by Sonu Shamdasani. English translation by Shamdasani, Mark Kyburz, and John Peck. W.W. Norton & Co. 404 pages, $195.

By Helen Epstein

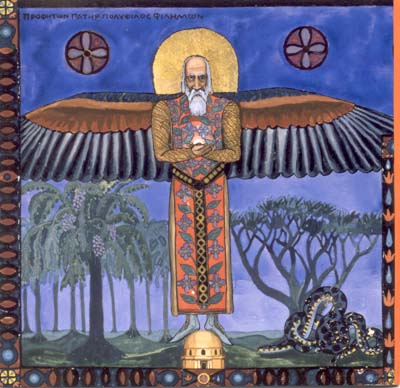

C. G. Jung's image of Philemon, his spiritual guide

In its Red leather cover, its language and its ornate calligraphy, “The Red Book” reads as a revelation of a new (religious) psychology, which – for Jungians – it is. The underlying narrative is, like many myths and memoirs, the spiritual quest of a man who loses his soul and undertakes a journey to find it.

Jung repeatedly rejected the idea that the “Red Book” was an artistic product – either literary or visual. He insisted that his journey through his unconscious was that of a psychologist, and that working through his visions and the meaning of the symbols in them would result in a new understanding of psychotherapy.

The psychiatry of his time, he believes, was incapable of distinguishing between deeply spiritual experiences and psychopathology. He, on the other hand, believed it imperative to utilize the terrors and beauties of his self-induced spiritual visions and integrate them into consciousness. His “journey” into self, his “journaling” of it, and his belief that the individual had the means to cure him or herself from within thus became the model not only for a psychotherapy of self-realization (Jung called it “individuation”) but for much of the New Age literature in our bookstores.

The “Liber Primus,” or first part of the “Red Book”, consists of a Prologue and eleven chapters with titles such as Refinding the Soul, Experiences in the Desert, Instruction, Resolution. They are written in tiny, cramped calligraphy, two or three columns to a page, with some small but no large illustrations. The first initial is an illuminated D for Der Weg (The Way) embellished with a pot of fire and a crowned black serpent, surrounded by the scene of a lake, a lakeside town with church, and the background of mountains against an azure blue sky.

In this first book he restricts his illustrations to historiated initials like that first D, which is followed by Latin calligraphy that invokes Isaiah (Who hath believed our report? And to whom is the arm of the Lord revealed?) and the Gospel of John (And the word was made flesh, and dwelt among us…) then Isaiah again. When Jung begins in his own voice, he writes:

“If I speak in the spirit of the this time, I must say no one and nothing can justify what I must proclaim to you….I have learned that in addition to the spirit of this time there is still another spirit at work, namely that which rules the depths of everything contemporary. …The spirit of the depths has subjugated all pride and arrogance to the power of judgment. He took away my belief in science, he robbed me of the joy of explaining and ordering things, and he let devotion to the ideals of this time die out in me. He forced me down to the last and simplest things.”

The First Book includes this encounter and dialogue:

“I: Who are you?

“E: I am Elijah and this is my daughter Salome.”

“I: The daughter of Herod, the bloodthirsty woman?”

“E: Why do you judge so? You see that she is blind. She is my daughter, the daughter of the prophet.

“I: What miracle has united you?

“E: It s no miracle. It was so from the beginning. My wisdom and my daughter are one.

“I am shocked. I am incapable of grasping it.”

The figure of Elijah eventually morphs into another old man whom Jung called Philemon and adopted as his spiritual guide. In Roman mythology, the (pagan) Philemon and his wife Baucis, offered hospitality to the gods Jupiter and Mercury when they went from house to house in disguise and no one else would take them in. Jung painted him into the “Red Book” where Philemon represents superior insight. The psychiatrist regarded him as his guru and he reportedly conducted conversations with Philemon as he walked through his garden.

While all this was going on in his mind, Jung was maintaining a growing private practice that was attracting both local and international patients (including some, spectacularly wealthy, Americans), maintaining a presence at Zurich’s Psychoanalytical Association, performing his annual obligatory military service, maintaining a lecture schedule that involved a great deal of travel, having meals with his wife and children every day in the dining room, analyzing his waking fantasies with his lover in his study, and lecturing on behalf of the international psychoanalytic movement.

He finally resigned his presidency of the IPA in 1914 and was ostracized by the Freudians as an apostate.

In addition to keeping track of his own dreams and waking fantasies, Jung began to urge his patients to produce their own, to paint them out, and then use their time in session to examine and integrate them.

One American patient, Christiana Morgan, wrote down his instructions into her own journal of 1926 and later presented him with her own “Redbooks” (that, according to her biographer, Jung used to suit his own theories).

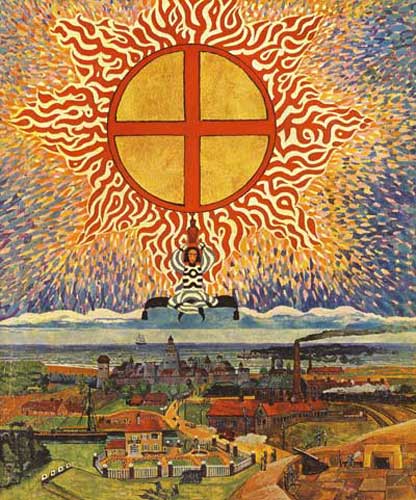

Image from the Red Book

After producing what he called “active imaginations” in session, without hypnosis, Jung advised her to “put it all down as beautifully as you can – in some beautifully bound book. It will seem as if you were making the visions banal – but then you need to do that – then you are freed of the power of them. …when these things are in some precious book, you can go to the book & turn over the pages & for you it will be your church – your cathedral – the silent places of your spirit where you will find renewal. If anyone tells you that it is morbid or neurotic and you will listen to them — then you will lose your soul – for in that book is your soul.”

The “Liber Secundus” is more varied in style. The tight tiny columns of text give way to large and sometimes huge calligraphy and full and half-page images. It has 21 chapters and begins with another big historiated D for Die Bilder (The Images of the Erring), this one enclosing an eye with a red pupil against a geometric pattern of colors.

The Second Book begins with a text from Jeremiah in Latin “Hearken not unto the words of the prophets that prophesy unto you: they make you vain: they speak a vision of their own heart, and not out of the mouth of the Lord.” And a second, “What is the chaff to the wheat? saith the Lord.”

The images, like the text of the “Liber Secundus,” cover a wide range of styles and moods. They include miniatures, sketches, watery evocations of dreams that bring to mind the work of William Blake, full-page tempera landscapes with symbols and figures rendered in great detail; decorative patterns in deep reds and blues that evoke Oriental art; others that resemble the pale Ravenna mosaics that impressed him; as well as work that is indistinguishable from psychedelic art.

The “Liber Secundus” is followed by “Scrutinies,” a reconsideration and revision of the material that precedes it, and a series of mandalas that he originally sketched into notebooks during his annual reserve duty in the Swiss military and then reworked for the “Red Book.”

In addition to echoing the style of many of the texts he took in over the years – the Old Testament, The New Testament, the various non-Western holy books, and the major writers of the European intellectual tradition, Jung can also sound very much like his contemporaries Herman Hesse and, poet/philosopher Khallil Gibran: “The knowledge of the heart is in no book…but grows out of you like the green seed from the dark earth. ”

But some of the “Red Book” has a distinctly contemporary quality, and brought to mind Bob Dylan: “The images of Eve, the tree, and the serpent appear. After this I catch sight of Odysseus and his journey on the high seas. Suddenly a door opens on the right and the old man says to me “Do you know where you are?”

As I dipped in and out of reading Jung’s text and staring at his intriguing, often beautiful, sometimes compelling images, I found myself needing more context. I consulted books by and about Jung – everything from his problematic “Memories, Dreams, Reflections,” an uncertain mix of memoir, biography and edited interviews that the publishers Helen and Kurt Wolff tried for years to get him to complete; the biographies by Blair and Hayman, Claire Douglas’ “Translate This Darkness : The Life of Christiana Morgan”; Laurens van der Post’s admiring memoir; and even the satirical and reductive “Jung for Beginners,” which includes a very helpful glossary of Jungian terminology.

I also went to see the exhibit, featuring the original, leather-bound “Red Book,” at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City.

The RMA, specializing in the art of the several cultures traversed by the Himalayas, is a spectacularly well-endowed, five-year-old museum, housed in the retrofitted former Barney’s clothing store off Seventh Avenue and 17th St in Chelsea. “The Red Book of C.G. Jung: Creation of a New Cosmology”, is one of three overlapping exhibits called The Cosmology Series, investigating how different cultures have visually represented the universe, from the solar system to the self.

The small, compact and rewarding exhibit runs until February 15, 2010, and begins with two small landscapes of the Swiss countryside that Jung – an amateur painter – had made, along with other oils on cardboard. The original “Red Book” is displayed in a glass case. Other cases allow you to walk through his creative process. They show some of the original black notebooks into which he jotted his dreams and waking visions, the sketches that were source material for the “Liber Novus,” and pages from the typescript that Jung showed to colleagues and revised before writing his final version in calligraphic form.

To complement the exhibit, the RMA has programmed a series of Redbook Dialogues –- conversations between analysts and assorted other people –some quite famous, some relatively obscure. Each begins with a reading from the “Red Book” and a projection of one or more of Jung’s images onto a large screen. The dialogue then takes off to wherever the two people onstage wish to go in the spirit of Jung’s work.

The very interesting dialogue I attended paired Sas Carey, a holistic nurse, Quaker and spiritual guide from Vermont, with Dr. Eric Hollander, a New York psychiatrist and expert on autism. Gray-haired, diminutive Carey has been traveling to Mongolia, partly by plane, partly on horseback, for 15 years to research the practices of local shamans. Eric Hollander, whose tall confident bearing recalls C.G. Jung’s, is former Chair of Psychiatry at the Mount Sinai Medical Center.

The psychiatrist spoke in scientific language, e.g. “core symptoms, social deficits, and repetitive behaviors.” The healer conveyed the persona (to use one of the many Jungian terms that have become part of our daily language) of a practitioner of alternative medicine: “My hands are guided by a knowing force.”

The pairing of these two strikingly different medical professionals, got me free associating back to the binary principle that runs through Jung’s life and work: male and female; good and evil; his personalities #1 and #2; the “spirit of the times” vs. “the spirit of the depths,” anima and animus, the shadow and the light – an approach that seemed out-of-date and of limited value to a dialogue co-sponsored by the National Autism Association and attended by an audience comprised largely of families of autistic children and the professionals who work with them.

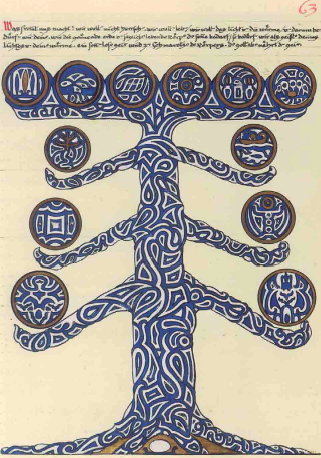

Image from the Red Book

After a brief consideration of Jung’s images, Carey talked about going to Mongolia, where she worked with the shaman brought to western attention in the memoir and film “The Horse Boy,” a little boy with autism whose parents take him to Mongolia in search of a cure.

During the Q and A, audience members made clear their frustration with the limits of western science and its alternatives. The two experts onstage did their best to respond to and open up these issues, in what seemed to embody the best of Jung’s multi-cultural, multi-disciplinary legacy but it was clear that, one hundred years after Jung’s time at Burghölzli, there are still far more questions than answers in the treatment of mental illness.

Watching these two sympathetic healers address autism brought to mind Jung’s multitudinous interests: parapsychology as well as psychiatry, the European as well as many non-western traditions of arts, medicine, and culture, the Christianity that imbued his spiritual life and his crucial role in introducing such non-western spiritual classics as the “Tibetan Book of the Dead” and the “I Ching” to the West, his interest in the esoteric theories of alchemy, and his use of psychotherapy both to cure the mentally ill and as a means of connecting the individual unconscious to the world.

“The Red Book” and the RMA’s Red Book exhibit and programming (including interviews and Jung-influenced films) which continues through February 15, 2010 means many different things to different people. Whether you’re a Jungian or a Freudian, think Jung was a genius or charlatan, or even if you’re someone who’s never given much thought to psychotherapy, it’s worth a visit.

Helen Epstein’s essay on “Narrative in Memoir and Psychoanalysis” appears in this winter’s issue of “Psychoanalytical Perspectives” and in the newly published “Ecrire la Vie.”

Jung Red Book – No one before Jung went into the unconscious more consciously.

Jung’s work fell into a natural dichotomy. On the one hand, his clinical practice was conducted in a relatively straight forward and public manner and yielded a remarkable success rate, leading to Jung being embraced as a revolutionary physician. On the other hand, there was Jung’s ‘mystical’ being, which involved the convergence of Jung’s personality, which was undoubtedly empirical, with the archetype of The Old Wise Man.

For outsiders, the idea, which Jung put forward variously in his later works – of incarnating one’s own myth, is quite foreign. The Red Book, so far as can be determined, is a record of the process of ‘psychical objectification’ of Jung’s personality. The reason it was not written up as notes, is because the process is ‘real’, not intellectual, and therefore it demanded the response of the whole man – the artist, Jung, as well as the scientist, Jung.

No one, who has not had a brush with this level of the unconscious, could possibly understand what Jung expressed in the Red Book, and though Jung realised, that in many cases any level of awakened awareness of the unconscious was dangerous, nevertheless for those who could profit, with guidance, it was a process worth undertaking.

The illumination derived from Jung confronting his ‘universal pre existent psychical counterpart in the unconscious’ – ‘The Self’, changed Jung irrevocably. For the personality to mine the unconscious, as Jung did, not only changes the man, but also changes reality. To usurp the unconscious and to deprive it of even a fraction of it’s power to control events and human destiny is an immeasurable victory for consciousness. Jung was more discreet, but he knew the value of this unique type of consciousness in an otherwise unconsciously determined universe.

Jung’s natural assumption was that others would take up the challenge of The Unconscious, but the status of a living mythological being elevated Jung to such a high place of reverence that his work with the unconscious was unsurpassed among his followers. His detractors, searching out the dirt of his human existence, (which he never denied), devalue his work by pointing to his human fallibility and mystical nature, not realising Jung’s message was precisely: THAT THE PERFECTION OF THE HUMAN SOUL IS ONLY RELATIVELY REALISABLE THROUGH THE PROCESS OF HUMAN INCARNATION. With Jung, this is overwhelmingly the case, especially since, and unavoidably, such latter empirical judgments are being applied illegitimately and unconsciously to the perfection of The Central Father Archetype, around which The Old Wise Man Archetype eternally orbits.

The confusion, between the empirical and the mythological, is at the root of most religious dilemmas and it is only latterly that we are getting glimpses behind the curtain at the empirical qualities of such mythologically imbued beings and events as are represented in the Christian texts of The New Testament. Jung was quite aware of this process and said so in his book Answer To Job. This book was a revolution in thinking about divinity, and his questioning and confrontation of the Old Testament God, in relation to the drama represented by the persecution of Job, is completely redolent of the way he conducted himself in relation to his Red Book fantasies. Jung was taken so seriously as a public figure in his time, that Answer To Job raised an unholy storm of indignation among the faithful in his predominantly Christian readership and following. The book also appears to have fulfilled a secret and terrifying childhood vision Jung had of God defecating on his own church.

Jung saw that the perfection of divinity (as represented by the bible) was far from conclusive, and to a more complete mind, covering up such inner contradictions – as seemed evident in the Deity, would stand as a barrier to the form of natural and spiritual self realisation represented by the process he had undertaken and was privately recording in the Red Book, which finally became the process of psychological Individuation.

The Red Book therefore, is as much a work of art as it is of science. It is one special man’s headlong journey into an interior world of meaning and power, yet because Jung occupies such a central point – through his psychical objectification, it is a journey that is valid for all.