Book Review: Edmund Wilson — A Paleface of a Redskin, Part 1

By Bill Marx

Those uncomfortable with Edmund Wilson’s eccentricities suggest he should be admired, but dutifully, like a Roman statue stuck in the far corner of the lawn.

Edmund Wilson: A Life in Literature (Paperback) By Lewis M. Dabney. Johns Hopkins University Press, 672 pages, $25.

Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s & 30s (Library of America #176) By Edmund Wilson. Edited by Lewis M. Dabney. 1026 pages, $40.

Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1930s & 40s (Library of America #177) By Edmund Wilson. Edited by Lewis M. Dabney, 1000 pages, $40.

Back in the ’30s, Philip Rahv memorably divided American fiction writers into redskins and palefaces — Mark Twain epitomized the wild men, Henry James the civilized — a chasm that today may be outmoded or politically indelicate. But Lewis M. Dabney’s fine biography of Edmund Wilson suggests that when it comes to assessing literary critics these categories may still have some definitional kick.

If H. L. Mencken is the quintessential redskin critic, then Lionel Trilling counts as a paleface. In this context, Wilson’s five decades as a man of letters, during which he producd volumes of review-essays, fiction, poetry, and journals, including such enduring accomplishments as Axel’s Castle, To the Finland Station, and Patriotic Gore, makes him both. And that volatile duality, his unruly combination of the raw and the cooked, the insider and the outsider, is what makes him such an inspirational odd man out in the history of American literary criticism.

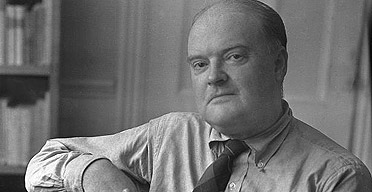

Those uncomfortable with Wilson’s eccentricities suggest he should be admired, but dutifully, like a Roman statue stuck in the far corner of the lawn. The embalming began while Wilson was still alive, with his own theatrical complicity. Many of the writer’s fans saw him — a pudgy man with a high-pitched voice, astonishing intellectual curiosity, and imperious manner — as a toga-clad emperor of literature. This view congealed into a reluctantly approving vision of Wilson as a brilliant but narrow-minded popularizer whose achievement — in an era in which literature is increasingly studied in academe by way of close readings and various varieties of theory — looks more absurdly pale-faced as the years go by. In his best books and essays, Wilson sought to depict the lives of his subjects, which range from Karl Marx to John Jay Chapman, as versions of a secular Pilgrim’s Progress, dramatic rites of passage in which the vulnerable artist not only attempts to heal conscious or unconscious wounds in his writing, but also fights for humane values amid political benightedness. According to Dabney, “in Wilson’s pragmatic, post-Darwinian aesthetic, artists are antennae of the race, registering its difficult effort to move ahead.”

Born in 1895 in Red Bank, a prosperous town along the New Jersey coast, Wilson endured a repressed, upper-class childhood. His mother wanted the boy to be an athlete; his lawyer father was aloof and mentally unstable. Wilson settled into a lifelong pattern of boozy introspection — he wrapped himself in a world of books while fending off formidable emotional problems. He had a mental breakdown in the late ’20s before completing his first significant book, 1931’s Axel’s Castle, a penetrating exploration of modernism that was the bracing fruit of Wilson’s most rewarding period as a literary critic: his reviews (including prescient pieces on Hemingway) are generally balanced, supple, and learned examples of analysis, confident of their opinions and angles of attack.

After enjoying the Jazz Age in Greenwich Village, Wilson became a half-hearted socialist. He eventually completely rejected communist dogma, repudiating the heroic vision of Lenin in his masterful 1940 study of the intellectual heritage of Marxism To The Finland Station. The pieties of the Cold War and the complacent hedonism of the post-war period weakened Wilson’s confidence that the conversation between criticism and the arts, which served as a means for civilization to reflect on its highest values and beliefs, pushed society ahead. In the last three decades of his life (Wilson died in 1972), the critic held true to his engaged vision, but in a more unruly fashion, drifting away from reviewing to publish a curious series of books; mingled skeins of politics, reportage, autobiography, fiction, and belles lettres. His idiosyncratic but insightful study of American Civil War writings, 1962’s Patriotic Gore, is the strongest volume from the latter part of his career, though 1969’s nostalgic Upstate also serves up elegant chunks of stoic meditations touching on nature, heritage, and aging.

As for Wilson’s private life, Dabney recognizes the wisdom of Wilson’s third wife, novelist Mary McCarthy, who tartly summed up the critic’s contradictory selves: “`He was two people. One the humanistic Princetonian critic and the other is a sort of minotaur, really, with his terror and pathos.” The biographer chooses to focus on the humanist rather than the monster — Wilson’s tempestuous relationship with McCarthy is sympathetically viewed, with neither rampaging beast let off scot- free. Wilson was married four times and had three children, none of whom see him as a model father, though the biography shows that Wilson tried, particularly when he became older, to break down what his son Reuel called his “unapproachablility.” For Dabney, Wilson’s alcoholism, along with his melancholy and orneriness, made domestic peace an impossibility. “Wilson was the only well-known literary alcoholic of his generation whose work was not compromised by his drinking,” claims Dabney, “but the alcohol undermined his marriages.”

According to his last wife, the long-suffering Elena Thornton, marriage to Wilson was “hell with compensations.” Dabney doesn’t deny Wilson’s devilish grumpiness, but there are a few amusing stories to make Wilson the bear bearable. During a Christmas party poet Theodore Roethke sat next to the critic on a couch and “leaned over, grabbed one of Wilson’s jowls in his massive hand and remarked, ‘Why, you’re all blubber!’” The recompenses of dealing with Wilson are recounted as well, and include the critic’s friendship and generosity with other writers, such as the Russian expatriate Vladimir Nabokov and Canadian Marie-Claire Blais.

For his favorites, Wilson was quick with a recommendation for a grant application or a blurb. In fact, the critic often went overboard with praise when reviewing his friends, which he had the bad habit of doing. The biography also offers a detailed summing up of what happened when the famous friendship between Wilson and Nabokov went sour. The former’s lukewarm response to Lolita eventually led to a bitter feud between the pair over the merit of Nabokov’s translation of Eugene Onegin into English.

Those deeply fascinated by Wilson’s sexual fetishes should turn to Jeffrey Meyers’s more clinical 1995 biography (in which it is alleged that Wilson “never met a foot he didn’t like”) and David Castronovo and Janet Groth’s recent book Critic in Love: A Romantic Biography of Edmund Wilson, which gives thee lowdown on Wilson’s crushes, including a yen, near the end of his days, for comedian Elaine May. Of course, Wilson helped out the voyeur contingent by keeping a meticulous scorecard of the women in his life: his five decades of journals and notebooks are crammed with clinical descriptions of lovemaking sessions with prostitutes as well as an impressive line-up of writers, from Edna St. Vincent Millay and Louise Bogan to Leonie Adams.

Dabney could have done more to explore the weird contradiction between Wilson’s sexual appetites (and their appearance in his fiction such as 1958’s The Memoirs of Hecate County) and the puritanical strain in his criticism. Wilson found some of the writers he analyzes in Axel’s Castle (Proust, Joyce, Yeats) too “unwholesome” for his taste, which suggests the limitations of his rationalistic stance. At times Wilson could be impatient with, even afraid of, the irrational: his critical method, which leaned heavily on Freud, arose out of his need to ward off his personal devils, not just to explain the complexities of modernism.

Dabney could have done more to explore the weird contradiction between Wilson’s sexual appetites (and their appearance in his fiction such as 1958’s The Memoirs of Hecate County) and the puritanical strain in his criticism. Wilson found some of the writers he analyzes in Axel’s Castle (Proust, Joyce, Yeats) too “unwholesome” for his taste, which suggests the limitations of his rationalistic stance. At times Wilson could be impatient with, even afraid of, the irrational: his critical method, which leaned heavily on Freud, arose out of his need to ward off his personal devils, not just to explain the complexities of modernism.

Wilson’s thought melded a supple rationalism to a robust moralism: the tincture of fatalism in the mix was an intriguingly darkening spice. When writing about books or personalities he favored a biographical approach, reinforced by the lean classicism absorbed during his studies of the 19th-century French critic Hippolyte Taine and classes with Christian Gauss, the critic’s beloved teacher at Princeton. The result is a lucid prose style — marked by an agile compression of psychological insight and critical acuity — that on occasion rises to a blunt lyricism. His writing also exudes a refreshing sharpness rooted in his cranky impatience with the modern intellect’s increasing proclivity for making a fetish of ambiguity. His most memorable pieces manage to combine a cool empathy with dovetailed notes of the magisterial and the no-nonsense.

Wilson’s treatment of criticism as a form of analytic story-telling could be revelatory, especially when he dealt with such congenial writers as Pushkin, George Bernard Shaw, and Kate Chopin. But the approach could get Wilson into gauche trouble, especially when he picked up a fat-headed Freudian hammer to nail an author’s psychic weak spot, using Oedipal hang-ups to solve literary enigmas. His essay on the sexual fantasies that underlie the genesis of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw is a notorious misfire, though in the same collection of essays, 1948’s The Triple Thinkers, Wilson’s decision that the writings of Ben Jonson are the creative fruits of anal retention is also downright embarrassing: “Ben Jonson seems an obvious example of a psychological type which has been described by Freud and designated by a technical name, anal erotic, which has sometimes misled the layman as to what it was meant to imply.” This “enlightened” approach makes T.S. Eliot’s reasonable celebration of Jonson as a satiric moralist, a perspective Wilson takes to task, look positively progressive.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Books, Edmund-Wilson, Library-of-America-Philip-Rahv, Mary-McCarthy, Patriotic-Gore, Persona Non Grata, Reviews, axels-castle, lewis-M.-dabney

Brilliant analysis. But Rahv made that distinction in the Thirties, not the Fifties.

Josh is right — Rahv wrote the essay in the late Thirties. I am making the change. Thanks.

Can anyone help me in getting exact quote of Frank Kermode on Edmund Wilson dividing five types of book reviewers?