Short Fuse: Eternal Recurrence — Freud, Marx, Mao Zedong Thought

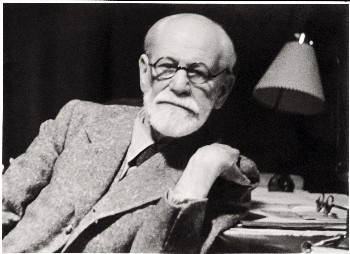

What I do suspect though, and find evidence for in Bloodlust, is that Freud is immune to any final dispatch or disproof, and will likely, through one portal or another, go on reinserting himself into our culture.

One of the responses to my review of Russell Jacoby’s Bloodlust asked why, given my feeling that Freudianism, at this point, is more a worn out dogma than a plausible source of fresh insight, I “bothered to read an essay/book based on Freudian thinking? Where could it go?”

Fair question. My answer is that over the course of his career, Russell Jacoby has proved to be a challenging, independent thinker, worth reckoning with. And it was only in the course of reckoning with Bloodlust that it became clear how much in thrall to Freud Jacoby was or had become—how much, for him, Freud was the man who, properly queried and deciphered, could still yield up oracular responses to basic questions, such as the origin of human violence. I don’t buy that for second and don’t think Jacoby makes much of a case for it in his book.

What I do suspect though, and find evidence for in Bloodlust, is that Freud is immune to any final dispatch or disproof and will likely, through one portal or another, go on reinserting himself into our culture. In that way, he resembles Marx, the other master narrator postmodernists hoped to depose in their challenge to the grand system builders, the theorists of totalistic—all-consuming, all-constricting—worldviews.

Perhaps Freud and Marx are exorcism proof. They are not the only ones. It might be useful, as point of comparison, to forget the manifold differences and consider for a moment the status of Mao Zedong thought in China, where Mao has had, of late, a resurgence in popularity. I’m not saying Maoism will ever again be supreme in China, only that it will be recurrent, have its turn to speak, and never be fully silenced.

But back to more familiar territory. Terry Eagleton, erstwhile theoretician of the English New Left, has recently published Why Marx Was Right, his effort to rescue Marx from the detotalizers. That book, in turn, comes directly on the heels of his Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate, a muddled effort to rescue religion in general, and Catholicism in particular, from Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, and other “new atheists.” Eagleton clearly wants it all—the Catholicism he grew up with, the Marxism he grew into. He’s like an infant trying to suckle at once on both the pink and the purple pacifiers. At least he has no need of a Freud nipple.

Others do, though I wonder how easy it would for them be to sustain a taste for Freud if they read Peter Kramer’s Freud: Inventor of the Modern Mind (2006). Kramer’s point of departure is the contrast between Freud’s self-congratulatory accounts of his therapeutic encounters with reports by his patients. “In forty-three cases,” Kramer writes, “patients had described their analyses with Freud, via essays, diaries, correspondence, or interviews. In thirty-seven of these therapies, Freud had given advice, expressed opinions, or urged the patient in a particular direction. In the remaining six cases, he had broken other of his stated rules for the proper conduct of treatment.”

Freud, Kramer finds, rarely “conducted ‘Freudian’ psychoanalysis.” And the advice Freud offered, contra his avowed standard of conduct, which was to offer none, could sometimes be disastrous. In the notorious Frink affair, Freud directed two patients under analysis—Horace Frink and Angelica Biju—to divorce their current spouses and marry each other, which they did. When their “marriage collapsed,” Kramer writes, “Frink became actively suicidal.” Freud urged Bijur to stay mum quiet about his role in the debacle, which, if it were known, might proving damaging to the psychoanalytic movement.

For Kramer, who had “loved and admired Freud,” the effect of this research was “unsettling.” Freud’s stature had been based, first of all, on “opposition to deception, hypocrisy, and authoritarianism” but it now seemed that “his behavior seemed to exemplify those very vices.”

The Freud Kramer winds up with is more fabulist than scientist, more crystallizer and consolidator than original thinker. Freud, finally, is a gifted storyteller, weaving salient cultural threads of his day and age—especially the new, widespread conversation about sexuality—into compelling, arresting forms. In The Interpretation of Dreams, for example, “Freud casts himself in the mold of his fictional contemporary Sherlock Holmes, detecting the obscure in the seemingly obvious and the obvious in the obscure.”

It’s not as if Kramer rejoices in deflating Freud. And he continues to credit him for helping to bring psychotherapy into existence. In a 2006 Boston Globe interview I did with him about his book (see below) h e said, “You can’t say Freud’s particular psychotherapy stems from the most legitimate view of the human mind and is most effective. But there is something about spending time with a concerned person and engaging in some thoughtful project about the self that seems valuable to people.”

If anything, Kramer mourns the absence of the framework Freudianism had provided for psychotherapy. “It isn’t that we now have some theory that’s better than Freud’s,” he told me. “There’s a sense of loss. . . . I can sit across from another person–I’m going to do it this afternoon a few times–but what is the basis for my responses when someone behaves or talks in a certain way? There are many kinds of psychotherapy. Why is one better than another? We’re agnostic now. It’s not that Freud has been superseded by a better theory of mind. We do without.”

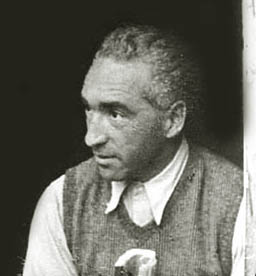

Perhaps it’s just this absence of a satisfying theory of mind that serves as standing invitation for the reemergence of one sort or another of Freudianism, however denatured. But perhaps not. In his review of Christopher Turner’s Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came to America, a biography of Wilhelm Reich, Kramer comes to a surprising conclusion.

Reich, let us recall, was the disciple of Freud who broke away to bring key psychoanalytic concepts to what he thought were their logical conclusions. Reich built orgone boxes to collect sexual energy and argued that if sexual repression was the problem, then what Norman Mailer—for a time, fascinated by Reich—called “the apocalyptic orgasm” was the only solution. Reich published charts diagramming every stage of complete sexual release. Anything less made for submissive, armored personalities, prey to domination by dictatorial forces. For Reich, it wasn’t self-knowledge, not attention to the “unrememberable but unforgettable” experiences of childhood that set you free: it was the perfect orgasm.

It may seem completely dated now, but in books like Selected Writings: An Introduction to Orgonomy and The Mass Psychology of Fascism, Reich fused sexual liberation to political liberation, in a way that garnered attention from the likes of Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Paul Goodman, and, as stated, Norman Mailer. Kramer, though, sees a more sedate and unsuspected resolution to Reich’s revolt against Freud. It is now Reich not Freud, according to Kramer, who presides over the psychotherapeutic encounter.

He writes: “To Freud, with his interest in slips of the tongue, words were the principal expression of mind. [But] the mainstream went on to adopt Reich’s view that how patients act is as relevant as what they say. With Reich, the defenses—narcissism, passive aggression, and the rest—moved to the fore. . . . Freudian therapy as conducted today is closer to Reich than to Freud.”

It is ironically the explosive Reich, according to Kramer, who keeps Freud out.

For now, anyway.

Boston Globe

December 10, 2006

Q&A Peter Kramer

By Harvey Blume

When I phoned Peter Kramer recently to talk about his new book, Freud: Inventor of the Modern Mind, he said the volume represented his “most negative” encounter yet in a “lifelong series of encounters” with the work of Sigmund Freud. Given Kramer’s knack for summing up and helping to shape the zeitgeist—as demonstrated by his 1993 bestseller Listening To Prozac—a negative report from him is not good news for 21st-century Freudianism.

To be sure, Listening To Prozac had already nudged Freud toward the sidelines. Kramer argued in that book that antidepressants like Prozac promoted notions of the mind, the brain, mental health, and personal identity that conflicted with the psychoanalytic model. Kramer maintained that “modern psychopharmacology” was poised to become “like Freud in his day, a whole climate of opinion under which we conduct our different lives.”

But the Kramer of “Freud” is no longer content just to wait for psychiatric climate change; he demands it. That’s not because he’s more enthusiastic about psychopharmacology. On the contrary, in Against Depression (2005), he’s forthright about the fact that Prozac and related drugs have turned out to have only limited use in the treatment of clinical depression.

No, Kramer’s impatience with Freud stems from his having steeped himself in tales of psychoanalysis told by people who were actually analyzed by the master. These make up a sort of samizdat literature of psychoanalysis, widely at variance with the self-congratulatory accounts penned by Freud himself. Kramer, who is a practicing psychiatrist and a professor of psychiatry at Brown University, has written that he had once “loved and admired Freud.” But, he told me, when the new literature let him peek over “Freud’s shoulders into how he really conducted his cases and drew his conclusions, it was disappointing.”

Kramer attributes some of Freud’s success to his having been “an inspired storyteller,” adept, for example, at blaming patients when therapeutic disaster struck. Kramer is a skilled storyteller, too. His slim, absorbing book makes a strong case that Freud was crafty, despotic, and “focused single-mindedly on his own interests.”

BLUME: You think Freud will ultimately be remembered more as a great writer than as a scientist, don’t you?

KRAMER: I was just at a conference with my humanities colleagues—philosophers, literary critics, and so on. Freud had been so rich for them because of the sense that science had placed its imprimatur on him. I was the party pooper, saying science has withdrawn its approval.

BLUME: One of your complaints is that Freud wasn’t really very original.

KRAMER: True, but a lot of the things Freud championed that were not original have remained valuable, like psychotherapy. You can’t say Freud’s particular psychotherapy stems from the most legitimate view of the human mind and is most effective. But there is something about spending time with a concerned person and engaging in some thoughtful project about the self that seems valuable to people. Beyond that, we have difficulty specifying what goes on.

BLUME: Freud’s been attacked from many sides before. What’s novel about your book, it seems, is the focus on the difference between what Freud said about therapy and what many of his patients said.

KRAMER: I think that is new. I don’t think anyone before has taken a linear biographical approach and pulled in all this critical history. And what does Freud look like over the course of an intellectual life? He does look bad.

Let me admit that there may be a personal aspect to this. I am an atheist, of European Jewish origins. And it seems to me that if you are going to be an avatar of secular European Jewish thought, as Freud was, you should have your hands on the table every now and then.

BLUME: “Hands on the table” is a curious turn of phrase. Let me take up one implication and ask why Freud is so interested in masturbation.

KRAMER: Early on he needed some dynamic that connected mind and body. His answer had to do with the notion that if you didn’t release sexual energy the right way, you had these mental illnesses. He never got very far from that. Masturbation and coitus interruptus keep coming up as harmful to brain and mind. And we know from his letters he seems to have had remarkably little actual sex with another person.

BLUME: Again, what are you implying?

KRAMER: Look, one of the things I struggle with in this book is: How important was he? If he’s not like Darwin or Copernicus, if he was often wrong and wrong in ways that were apparent at the time, not just in retrospect, how is it he captured the imagination of an era? I think his focus on personal sexual history—masturbation, fantasy, maybe early escapades or traumas—was very interesting to lots of men and to lots of doctors. People in the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society, early on, were discussing their own sexual history. It was liberating to do that, though not especially rebellious. Here, again, psychoanalysis was about giving a scientific stamp to a central interest of journalism, fiction, and theater.

BLUME: So Freud crystallizes the zeitgeist?

KRAMER: To have your finger on the pulse of the zeitgeist is a form of genius. But being wrong is a problem. It’s clear to me that if Freud had never lived, medical science would be pretty close to where it is now.

BLUME: Still, much as you discredit Freud, you seem wistful about him. You seem to miss him.

KRAMER: We no longer have a comprehensive theory of mind. The neurological take, mostly, is that mind is effectively an illusion. But in our everyday life, we believe we have mind and self and continuous personality. Freud thought he had a system for saying how those are arrayed and develop. We’ve lost that.

Intuitively, we are Cartesians. We think there’s something that needs to be explained about the connection between mind and body. Freud was more optimistic than we are about getting it right.

BLUME: You write fiction, too. Your novel, Spectacular Happiness, a portrayal of a Cape Cod ecoterrorist who likes to swim and to read, had the bad luck to come out around 9/11.

KRAMER: [laughing] A month before 9/11. I comfort myself by thinking if it had come out a month later it wouldn’t have been better.

There’s a strain in my work that allows for lots of things to be psychotherapy. In Spectacular Happiness, a therapist thinks a good explosion or two might help bring his patients back into accord with themselves. But does liberating the self justify everything?

Tagged: Bloodlust, Christopher-Hitchens, Mao, Peter Kramer, Richard-Dawkins, Russell Jacoby, Sam Harris, Short Fuse, Sigmund Freud, Terry Eagleton

Elevating humans to status of demi-gods is as problematic as believing a drug (or ideology) can cure all.

Always better to think for yourself and find a middle way.

Hi,

In the context of this piece, not sure what you’re getting at when you say “Elevating humans to status of demi-gods . . . “