Judicial Theater Review #1: The Overwhelming at Company One

![]()

What is a Judicial Review? It is a fresh approach to creating a conversational, critical space about the arts. The aim is to combine editorial integrity with the community-making power of interactivity. This is our first session.

- Review by Ian Thal

- Review by Timothy Longman

- Review by Peter Cohen

- Artist response by Shawn LaCount

- Summary by Bill Marx

As coverage of the arts in the conventional, mainstream media wanes, critical discussion of the arts online has settled into two extremes: there’s the corporate dream of an omnipotent “Google” reviewer for all and the chaos of opinions fired off in individual blogs of varying quality and intellectual integrity.

My aim with the Judicial Review, of which there will be one a month in the coming year, is to fashion a mid-way between these two unsatisfying polarities — to create a flexible place where professionals and nonprofessionals, artists and amateurs can exchange views and judgments about the arts. This will serve as a model for a civil conversational setting that will invite independent discussion as well as encourage participation in the arts.

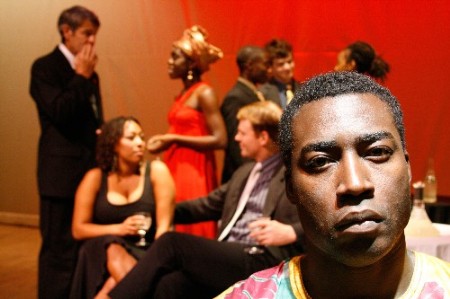

First on the docket for Judicial Review: John ADEkoje (Samuel Mizinga), and the cast of The Overwhelming

The inspiration for the Judicial Review is the U.S. Supreme Court. Arts events will be evaluated by local panels of “judges” who will post majority and dissenting opinions in the form of written reviews or via video- or podcasts. The panel will be made up of a combination of professional critics and non-professional observers.

Our goal is to introduce a supervised space for educational, passionate, and incisive conversation about the arts that draws on the strengths of various levels of expertise. By doing so, it is hoped that the judges will learn from each other as well as offer a variety of perspectives that will invite responses that will deepen readers understanding of the arts and the craft of criticism.

In any trial there is a place for a “Friend of the Court” brief. The Judicial Review will include a space for the artists themselves to have their say, to contribute to the respectful exchange. The arts organization under review will be invited to file opinions.

This idea is my response to the considerable challenges and opportunities that the web poses for criticism of the arts, reflecting my belief, after 30 years of writing and reading arts criticism, that a review’s verdict, while essential, is not its most important value. Criticism is at its most vital when it fosters spirited dialogue, when critics help us take the arts seriously by connecting creativity with our thinking and feeling selves.

For that kind of connection to thrive on the web the emphasis must be placed on the value of the collective give-and-take, on generating information and curiosity, on stimulating the slip and slide of reasons and evaluations. We have much to learn from each other. I invite those who would like to take part in this experiment as “judges” to email theartsfuse (info@artsfuse.org). I would also like reactions to the idea, suggestions for improvement, directions to take, etc.

Below I summarize the majority opinion of the three judges. Company One director Shawn LaCount then contributes a “Friend of the Court” brief.

— Bill Marx, Editor

==================================================================

The Overwhelming by J. T. Rogers. Directed by Shawn LaCount. Presented by Company One at the Boston Center for the Arts, Boston, through November 21, 2009.

Cedric Lilly (Joseph Gasana),

Doug Bowen-Flynn (Jack Exley) in The Overwhelming

The bottom line decisions of the three judges are pretty much the same: each felt that the production was worth seeing. Company One was praised for staging a script that deals with an international issue of moral and political importance.

Because it leans heavily on the tired notion of Americans as myopic innocents in a strange land (Rwanda in 1994), J. T. Rogers’s play ended up disappointing performer Ian Thal and playwright Peter Cohen. The dramatic set-up didn’t bother Timothy Longman, the Director of the New African Studies Center at Boston University, who was more disturbed that the script reinforces, rather than undercuts, clichés about Rwanda.

Dissenting Opinion: None really, though Peter Cohen strikes the harshest note regarding the Company One performers. He believes they are pitched at too high a decibel level.

Ian Thal

Any contemporary play that depicts Westerners abroad in the midst of what is euphemistically called a “human rights catastrophe” draws comparisons to Tony Kushner’s “Homebody/Kabul.” Whether or not the latter served as a model, J.T. Rogers’ “The Overwhelming” explores the weeks leading up to the 1994 genocide of Rwanda’s Tutsis through the eyes of visitors from America. In this case, the innocents abroad are the family of Jack Exley (Doug Bowen-Flynn), an academic attempting to track down a Tutsi Doctor and former college roommate played by Cedric Lilly.

Any contemporary play that depicts Westerners abroad in the midst of what is euphemistically called a “human rights catastrophe” draws comparisons to Tony Kushner’s “Homebody/Kabul.” Whether or not the latter served as a model, J.T. Rogers’ “The Overwhelming” explores the weeks leading up to the 1994 genocide of Rwanda’s Tutsis through the eyes of visitors from America. In this case, the innocents abroad are the family of Jack Exley (Doug Bowen-Flynn), an academic attempting to track down a Tutsi Doctor and former college roommate played by Cedric Lilly.

To Rogers’s credit, the protagonists encounter a supporting cast of Rwandans, expatriates, and diplomatic workers who pursue their own agendas and seize their own opportunities in a morally bewildering setting. These characters attempt to determine what the Exleys know, what they want the Exleys to know, what the Exleys believe, and what they want to Exleys to believe. These insiders act at cross-purposes to one another to enlist, distract, or shape the perceptions of the outsiders.

Rogers, however, fails to meet Kushner’s challenge: the play is undermined by the author’s reliance on the cliché of naive Americans bumbling far from home. Where Kushner’s Ceiling family is made up of memorable characters, Rogers’ Exley family are barely even stock: back in 1994 the script’s protagonist, a political scientist specializing in international relations and grassroots activism, would not be so foolish as to believe that UN peacekeepers would take action against human rights abuses. For two years running UN troops had already been passively witnessing ethnic cleansing in Bosnia. That Jack studies grass-roots activism yet praises his activist friend to a government official of a rival ethnic group is a ludicrous plot device: Rogers telegraphs to the audience not just the identity of killer and victim, but how the killer will be led to his victim.

Rogers wants it both ways: Jack’s supposed to be a nondescript everyman who serves as an audience surrogate yet also have the intellectual chops to turn up in the wrong place at the wrong time for the sake of a research project. (Rogers could have worked harder to make Jack sound more like a professor who was making a last ditch effort to land tenure.) Actor Bowen-Flynn is unfairly left in the position of having to pump life into a hero who is little more than a container for lazy plot devices.

The other members of the family fare slightly better because their naiveté comes by virtue of being along for the ride. Jack’s wife, Linda (Lyndsay Allyn Cox), is written as a narcissistic writer of creative-nonfiction, a stereotypical self-absorbed idealist blind to the genocidal rhetoric of anyone who promises her a look at The Truth. Ironically, the fact that she clings to her African-American identity blinds her to the encroaching menace. Jack’s teenage son, Geoffrey (Gabe Goodman) at least makes no pretense of understanding Rwanda and is thus the first to grasp what is happening.

Richer opportunities for the actors are found in the supporting cast: the nimble Tory Bullock, who plays Gerard, the porter whom Geofrey befriends, makes good use of the role’s possibilities for physical comedy. Cedric Lilly’s portrayal of the missing activist-doctor embraces both comedic subterfuge and the tragedy of the difficult decisions that have to be made in wartime. Mason Sand and Peter Brown (each in two roles) play a range of foreigners who see the precedents or harbingers of the oncoming genocide but because of world weariness, lack of actionable intelligence, or realpolitik savvy are unable to avert history. Because of Jack and Linda’s ignorance, these telling signs of the time and place are left addressing no one but the audience.

Director Shawn LaCount and stage manager Jillian Levine do an admirable job of keeping “The Overwhelming” running along at a fast pace and, despite the play’s considerable flaws, focused on the important themes that Rogers seeks to explore.

Ian Thal is a mime, commedia dell’arte actor, puppeteer, poet, playwright and teacher in Somerville, MA. His play, “Total War,” holds the dubious distinction of attracting protests despite never having a production.

Timothy Longman

When I first traveled to Rwanda in 1992, the country was largely unknown in the United States. “Rwanda,” several people asked me before I left for a year of research in the country, “Isn’t that a woman’s name?” Even in the immediate aftermath of the 1994 genocide, the country’s main claim to fame remained Dian Fossey and the movie “Gorillas in the Mist.” For the first several years, when I gave a public lecture about what happened in Rwanda, I was inevitably asked, “What about the gorillas?”

The terrible violence that swept Rwanda in 1994, killing as many as 800,000 people, ultimately caught the attention of the international community. While Burundi’s civil war was longer and Congo’s wars have killed more people, Rwanda has become the rare African tragedy that has garnered widespread notice in the West. A morbid fascination with the intimate nature of Rwanda’s violence has inspired a series of best-selling books, movies, and plays that have elevated the Rwandan genocide to iconic status. The name “Rwanda” has become shorthand for brutal, incomprehensible slaughter.

“The Overwhelming,” currently in a gripping and well-acted production by Company One, represents the most successful play to date about the Rwandan genocide, having been staged at the National Theater in London, the Roundabout in New York, and the Next Theatre in Chicago. The story centers on a naïve and idealistic academic, Jack Exley, who travels to Rwanda with his family in early 1994 to research a book on grassroots activism. Having organized the trip at the last minute at the invitation of an old Rwandan friend, Jack is ill informed and ill prepared for life in a country in the midst of civil war and political transition. Jack, his wife, Linda, and son, Geoffrey, develop friendships with several Rwandans. But none of their new friends are fully truthful, and they all seem to be involving the Exley family in secretive plans.

While “The Overwhelming” takes place in a context of spreading violence, the play itself is a mystery and psychological thriller. Set in the months just prior to the genocide, the play focuses on the mounting tensions in the country and the confusion of outsiders seeking to understand a complex and deteriorating situation. The play poses a series of moral questions. How would you react if confronted with violence? What would you sacrifice to save the life of a friend? Would you have the courage to do what is right when confronted with a life and death situation? How would you even know which choices are right?

Fedna Jacquet (Emiritha),

Gabe Goodman (Geoffery Exley) in The Overwhelming

As a moral parable about the naiveté of foreigners and the ambiguous line between right and wrong, the play’s setting in Rwanda is almost incidental to the story. Yet the fact that the end of the story is known, that the viewers know in advance that one group represented in the play is going to commit genocide against the other, undermines the plays intended mystery. Since we are already predisposed to believe that the Hutu in the play are evil and the Tutsi are victims, the audience is not drawn directly into the moral ambiguity but instead watches from a distance to see if and when the American characters will clue into the truth of the situation.

The final revelation that the Tutsi characters may not be entirely blameless serves as more of a distraction than a complication, since it cannot justify the attempt to annihilate all Tutsi from the face of the earth, as the Hutu Power militias ultimately sought to do.

The danger with fictionalized accounts of this sort is that the audience often focuses less on their artistic truths than on the window that they supposedly provide to an unfamiliar culture. While most have now heard of the Rwandan genocide, many people know only the vaguest details. As an audience talk-back following a recent Company One production demonstrated, many audience members turn to the play not only for inspiration but also for information. The idea that the play has a documentary authenticity is promoted by liner notes and press coverage touting the playwright J.T. Rogers’s research on the topic and travels to Rwanda and the real-life moral crisis he encountered in his own dealings with Rwandan consultants.

Unfortunately, the portrayal of Rwanda in “The Overwhelming” is inaccurate on a number of points. The play nicely captures the reticence of Rwandans, who are generally parsimonious with the truth in order to protect themselves. But Rwandans are also notoriously self possessed, keeping their feelings and true thoughts tightly bottled up. The displays of sharp temper and overt emotion at various points in the play do not ring true.

The factual details about events are also mistaken on several key points. The period in which the play is set was a time of sharply rising ethnic tensions, but there was very little violence, outside a few high-profile assassinations. The idea portrayed in the play that ethnic massacres were gradually spreading seems to suggest a much more random form of violence than the well-planned genocide a few months later actually represented.

Certain decisions in this production tend to emphasize the degree to which Rwanda is more of a symbol than an actual setting for the play. The decision to dress Rwandan actors in distinctly West African garb (a Nigerian Agbada and Ghanian Kente cloth) is jarring to anyone familiar with East Africa, as is the comical North African servant outfit worn by the Exley’s household worker.

These criticisms aside, I quite enjoyed Company One’s production. The story is compelling and the acting quite strong. As an evening of provocative and entertaining theater, I would highly recommend “The Overwhelming.” As a window into understanding Rwanda and its genocide, however, other more accurate sources are available. This play unfortunately does not push beyond the iconic status of Rwanda’s tragedy.

Timothy Longman is director of the African Studies Center at Boston University. He has traveled and researched extensively in Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa. He lived in Rwanda in 1992-93, conducting research for his dissertation, and he returned to Rwanda in 1995 to direct the Human Rights Watch field office. His book, “Christianity and Genocide in Rwanda,” was recently published by Cambridge University Press. He is currently completing the book “Memory, Justice, and Power in Post-Genocide Rwanda,” based on field research he conducted there from 2001 to 2006.

Peter Cohen

I found “The Overwhelming” a difficult evening of theater that often disappoints but ends quite compellingly.

Most certainly, “The Overwhelming” is not an easy play to produce. And for that alone Company One has my respect. They could have gone for the safe bet, fare that is easy to digest; instead, the troupe chose a story about genocide, set in the African country of Rwanda in 1994.

Given the shape the world is in, at present, this play is not an unreasonable choice – just think of Darfur or Mugabe’s Zimbabwe. Technically, Zimbabwe’s disintegration is not a case of genocide, but the violence that Mugabe and his clique have visited on it comes close.

Obehi Janice (Elise Kayitesi)

and Lyndsay Allyn Cox (Linda White-Keeler) in The Overwhelming

But while I understand the reason for presenting such a play, I have a problem with this particular one. The story is quite contrived; instead of vibrant, engaging dialogue you get speeches and little lectures; and instead of confrontations that reveal who the characters are, and what they struggle for, you get shouting matches. The director could have done more to stage the play in a manner to offset its shortcomings.

And yet the last scenes make up for much of that. All of a sudden you do have conflict – and a truly tragic one at that. And much of the effort that went into the play pays off. I will not reveal the play’s climax, except to say that in those final scenes we get a real sense of what happened at the time in Rwanda – how shockingly easy men (and women) lose their humanity, almost as if they had lost nothing more than an umbrella or a hat. And that what we hold to be enduring and reliable – our institutions, our values, our art – turns out to be of little more protection than a soap bubble’s skin.

The play has a quite large cast and the director, Shawn LaCount, does not always seem to know what to do with them all. But the troupe includes talented actors of African origin (and accent). In particular John Oluwole Adekoje, Tory Bullock, Chima Chikazunga and Obehi Janice – they all have cameo moments that breathe life into the play. But the flat dialogue makes it hard for everyone to shine for too long.

Finally, I wish the set-designer Sean Cote, had given more thought to the fact that the play is set in Central Africa – I missed the colors, the visual chaos of a developing country. Obviously such effects – for a small theater like Company One – are also a question of money. But not just; more could have been done, not with money, but with imagination.

So, again – if you are one of those people for whom the pleasure of going to the theater includes being challenged – go see this show. You will be rewarded with a powerful finish.

Peter Cohen studied at Princeton and Harvard. It was at Harvard, at age thirty-one, that he broke through with the non-fiction novel “The Gospel According to the Harvard Business School,” which became a bestseller. Cohen’s play with music, “A Ship to Zion,” was produced by a Kingston, Jamaica, company. It won its lead actor the Jamaican Oscar for best male actor; the original production was subsequently invited to Zurich, and to the Caracas International Theater Festival.

Some of Cohen’s plays have been produced by prominent European theaters such as: Schauspielhaus Zurich (in cooperation with Swiss National Radio); Kulturfabrik Kampnagel, Hamburg; Hackesches Hof Theater, Berlin; Theaterhaus Gessnerallee, Zurich and Theater Freiburg, Freiburg i.B., Germany.

In May 2009 a new play, “To Pay the Price,” got a full production Off Broadway; Bob Kalfin, a veteran of Broadway, directed.

=============================================================

Friend of the Court brief:

Director Shawn LaCount

First, I’d like to thank all of you for your thoughtful critiques. It’s great to be part of an ongoing dialogue on theatre, and I hope we’ll have more opportunities to engage like this in the future. I will say that as a founding member of the company dedicated to “changing the face of Boston theatre,” I would love to see some of the diverse faces in the Boston theatre community participating in the discussion.

First, I’d like to thank all of you for your thoughtful critiques. It’s great to be part of an ongoing dialogue on theatre, and I hope we’ll have more opportunities to engage like this in the future. I will say that as a founding member of the company dedicated to “changing the face of Boston theatre,” I would love to see some of the diverse faces in the Boston theatre community participating in the discussion.

It’s no surprise that three critics with different areas of expertise found different strengths and weaknesses in Company One’s production of “The Overwhelming,” and all of you have certainly given us a lot to think about. What I found most interesting, though, are the questions of cultural sensitivity and veracity raised by all three, so I think that’s where I’ll focus for this response.

With a play like this, I think we all – cast, crew, director, audience member – have an inclination to try to provide answers: what makes a genocide or a holocaust happen? But I don’t think we’re capable of that. They continue to happen all over the world, time and time again, even though we say we’ll never let them happen again. So at some point in the rehearsal process, we decided to move away from the idea of putting an academic or historical stamp on the events. It felt condescending, in a way – as if we were taking a superior national, cultural, or racial view.

That’s not to say the show doesn’t provide answers, but I think the answers are not political. I think the answers are individual, paralleling the country’s conflict with this family’s conflict, and speaking to how we make our decisions, specifically in the face of our deepest fears. I always think the concept of “fear” makes for good drama.

Like Professor Longman, I was troubled by the idea that the audience is seeking an historical record in this production, and if I can speak for the playwright, J.T. Rogers, I don’t think his recounting of his research is intended to give the piece a documentary authority. Our approach was not to educate, but to illuminate major questions – to put the audience in the shoes of many different characters, all asking, “What would I do?” If anything, “The Overwhelming” emphasizes that the very idea of truth is always subjective, and there is no neutrality when it comes to issues of life and death. I think that’s what makes it such a good story, and one that I wanted to take part in telling.

Tagged: Africa, Company One, Ian Thal, J. T. Rogers, Peter Cohen, Rwanda, Shawn LaCount, The Overwhelming

Prof. Longman:

I’m one of those folk who only know the vaguest details of the Rwandan genocide; but even then I had long been of the impression that it was a well-organized and efficiently executed effort. Consequently, when Rogers presents it as the series of ethnic massacres spilling into genocide, I took it on a matter of trust that Rogers had done the research to justify his contradiction of my “commonly held misapprehension.” So when you point out that these tales of massacres leading up to the genocide are largely fictions, it makes me further question Rogers’ intentions: Not only did I find the protagonist is uncompelling, but I left the theatre miseducated about hows and whys of the Rwandan Genocide.

That said, were there rumors of massacres that might have helped incite the Hutu to murder their Tutsi neighbors? Sufficient rumors to confuse foreign diplomats or human rights investigators? I ask only because I don’t know.

Also, as an academic, did you find the character of Jack Exley a believable portrayal of your profession? I realize that scholarship is highly specialized, but to my mind, he seemed to lack even the basic knowledge I’d expect to be within his stated areas of expertise. This, of course, was one of my biggest problems with the play as a piece of theatre as the story hinges on Jack’s ignorance.

The problem with this, as with so many works on Rwanda by casual observers, is that Rogers is not so far off from the truth. There were in fact repeated massacres in the period October 1990 through February 1993. Each was limited in scope and well organized by or with the support of the government (though they did try to make them appear random). These massacres helped to pave the way for the genocide, as methods of organizing killing were developed and people got used to ethnic violence.

The issue is that the period in which this play is set was a break before the major massacres. There were a couple of high-profile assassinations – such as the killing of Martin Bucyana that ends the play – but the idea that common Tutsi like Emiritha would have been killed during this period is just wrong. People did have to make the type of tragic moral choices that end the story (as you mention) during the genocide itself, a month or so later, but just not during this period.

Don’t get me wrong. Rogers gets a number of facts correct. For example, the idea that Hutu refugees from Burundi were deeply involved is accurate. But there are just enough details off here and there that it’s frustrating for someone who knows the country.

I’m reluctant to be too critical, because I thought that the acting was very strong. And how nice to see such a strong group of African and African-American actors. The Kinyarwanda in the play was even pretty good, which is saying a lot, because it is a very challenging language. And I thought Mason Sand had a great South African accent.

But there are indeed some problems with the script. I agree that Jack was less than compelling. I think that Rogers tries to use Jack’s failure to receive tenure as a cover for his cluelessness. And Doug Bowen-Flynn did a good job giving some depth to the character. But I did not find the entire set up very believable. At the same time, I have often encountered really clueless Westerners in Rwanda (and other parts of Africa). The type of character Jack represents is actually much more common in Rwanda today. I get regular contacts from people who naively say, “I’m going to Rwanda to do reconciliation. Do you have any advice?” My usual answer is, “Please don’t go.”

I’m certainly in agreement with you regarding the quality of the performances (which might not have been so clear since I spent more time addressing weaknesses in the script) and Shawn LaCount has to be commended again for holding things together. The problems stem from the script. It seems to me that with regards to this sort of play, it should be sufficiently well-researched an expert such as yourself should not be frustrated, just as an aspiring playwright such as myself should not be frustrated by problems with the narrative or central characters.