Short Fuse: Of Henry Kissinger, China, Stink Bugs, and the Games that Shape the Mind

“On China” boasts photos of Henry Kissinger’s numerous visits to China. In many you see him smiling hugely, brandishing chopsticks alongside the likes of Zhou Enlai. He’s enjoying making history — and the food.

By Harvey Blume

It struck me as ironic that Christopher Hitchens and Henry Kissinger were featured in the same (5/15/11) issue of the NYT Book Review. Hitchens was on the front page, reviewing Adam Hochschild’s To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1918. There was nothing particularly enlightening about the Hitchens piece: au contraire, it was just Hitchens being hissy. There is something of the stink bug about Hitchens in this, his practiced default mode.

Let me explain about the stink bug, aka the bombardier beetle. As Natalie Angier put it, that formidable insect comes equipped with “multistage weaponry”. This is because it “sequesters internal reservoirs of hydrogen peroxide and hydroquinone, and will mix the ingredients together with the proper enzymes as needed in a reaction chamber, to generate a boiling blast of defensive spray that can be aimed at an attacker through a swiveling nozzle in its anus.”

(Quite a beetle. Imagine what the military could do with a super-sized, trained troop in the trillions.)

But back to Hitchens. Hitch went to the best of the best English schools, including Balliol College, Oxford, seat of England’s governing elite, where he learnt rhetorical stink buggery [sic], if not necessarily other kinds, and has practiced and perfected its techniques over the course of his career. The Times Book Review has been calling on Hitchens often lately. That may be because Hitchens is combating esophageal cancer, and the Times is only showing proper respect for an embattled, multifarious writer. Or it may be, as has been noted of late, because literary disputes seem to be tweeted and Facebooked out of existence— bks? ltrtr? lol, 🙂 — which does nothing for the bottom line of the Times Book Review, or for newspapering in general. My suspicion is that Times editors feel a bit of Hitch’s noxiously “swiveling nozzle” may help boost marketable literary controversy.

However placidly they lay athwart each other in the 5/15/11 issue, Hitchens and Kissinger have long been intimately connected at, yes, the nozzle. Ten years ago, Hitchens published his book The Trial of Henry Kissinger, in which he called Kissinger to the bar for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The bill of particulars included: “The deliberate mass killing of civilian populations in Indochina”, and “the assassination of the inconvenient politicians, the kidnapping and disappearance of soldiers and journalists and clerics who got in his way.”

Hitchens concluded: “Whenever any major US covert undertaking occurred between the years 1969 and 1976, Henry Kissinger may be at least presumed to have had direct knowledge of, and responsibility for it.”

These are serious charges, and Hitchens breathed life into them. Nor has anything I know of washed Kissinger clean. But 2001 was, in historical terms, an axial year, a year, in other words, when the zeitgeist swiveled. It was the year Al Qaeda leveled the WTC, when President Bush, in response, bombed the Taliban out of power in Afghanistan in a war that seems, a full decade later, almost infinitely far from satisfactory conclusion. And in March, 2003, Bush launched the fateful invasion of Iraq. Dick Cheney was Vice President at the time, and Donald Rumsfeld Secretary of Defense. Both these men can be legitimately described as political progeny of Henry Kissinger.

Hitchens vociferously supported the march to Bagdad. But unlike other liberal hawks — Tom Friedman and George Packer, to name two — he never thought it necessary to reconsider. The fact that there were no WMDs in Iraq and no remotely plausible connections between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin laden occasioned no second thoughts for Hitch. Nor did it seem to trouble Hitchens, assuming he acknowledged it to himself, that Kissinger was in and out of the White House during the Bush years, and that Cheney and Rumsfeld were his disciples. This, more than his bombardier style, has, to my mind, left a lasting hole in Hitchens’s work and legacy.

Henry Kissinger, it should be stated, was a bane of my generation, a generation that came to adulthood in the 1960s. His was the imperturbable voice of the draft, of the bombing of Cambodia. No other voice — not Johnson’s, not Nixon’s — is more lastingly associated with the War in Vietnam.

Maybe because that was relatively old news, or maybe because I have felt perpetually and contemporaneously betrayed by Hitchens, in a way I could never have presumed to have been betrayed by Lord High Henry Kissinger, it was to the Kissinger piece in the Times Book Review — a review by Max Frankel of Kissinger’s On China —that I turned with greater interest.

But I had an ulterior motive for interest in Kissinger’s On China. As readers of my previous posts to The Arts Fuse may know, I play chess, both the version westerners take for granted — formally known as international chess — and the Chinese version, xiangqi, or elephant chess, which is likely, given the population of Asia, more popular across the globe.

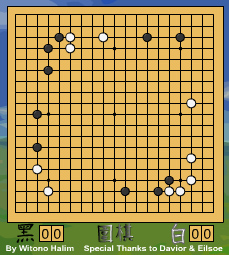

The Frankel review and others — notably a piece by Jonathan Spence, the preeminent Western scholar of Chinese history and culture — focused on the fact that Kissinger structured his entire tome on the difference between the premier Chinese and Western games of skill. The Chinese game was not, for Kissinger, Chinese chess, but the oldest game of pure skill known — weichi, better known in the West by its Japanese title, “Go.”

Kissinger writes:

Wei qi translates as a game of surrounding pieces; it implies a concept of strategic encirclement. . . . If chess is about the decisive battle, wei qi is about the protracted campaign. The chess player aims for total victory. the wei qi player seeks relative advantage. . . . Chess teaches the Clausewitzian concept of “center of gravity” and the “decisive point” — the game usually beginning as a struggle for the center of the board. Wei qi teaches the art of strategic encirclement. Where the skillful chess player aims to eliminate his opponents pieces in a series of head-on clashes, a talented wei qi player moves into “empty” spaces on the board. . . Chess produces single-mindedness; wei qi generates strategic flexibility.

The emphasis on the decisive import of wei qi is no mere aside for Kissinger. References to the game occur repeatedly in his book. For example, in discussing the post-World War II victory of Mao’s communist armies over Chiang Kai-Shek’s nationalists, Kissinger writes:

“Chiang’s Nationalist forces opted for a strategy of holding cities, while Mao’s guerrilla armies based themselves in the countryside; each sought to surround the other using wei qi strategies of encirclement.”

The paradigm of wei qi applies, for Kissinger, even to the war in Vietnam. He writes: “When the U.S. buildup in Vietnam began, Beijing interpreted it in wei qi terms: as another example of American bases surrounding China from Korea to the Taiwan Strait and now to Indochina.”

As for Vietnam, Kissinger adds: “Something in the almost maniacal Vietnamese nationalism drives other societies to lose their sense of proportion and to misapprehend Vietnamese motivations and their own possibilities. That certainly was America’s fate. . .”

That may be as far as Kissinger goes and can be expected to go in reconsideration of his sponsorship of the War in Vietnam. I wonder if Hitchens can ever be expected to go that far in reconsideration of his intellectual sponsorship of the hardly less ruinous war in Iraq.

***

Marshall Mcluhan argued tellingly that media shaped minds. Kissinger makes the same sort of claim for games: games shape mind, mold worldview, condition war, politics, and diplomacy.

It is certainly the case that the Chinese esteem and often refer to their traditional games — wei qi, xiangqi, even mahjong — in a way that has no parallel in the West. Kissinger quotes Mao praising mahjong “as a school for strategic thought.” He has Mao telling his doctor: “If you knew how to play the game, you would also understand the relationship between the principle of probability and the principle of certainty.”

This Maoist dictum provokes thought. Games of pure skill — all forms of chess, wei qi, checkers —have been viewed as triumphs of pure reason. But that victory deserves to be questioned, allied as it is to the philosophical bent for logic. Reason only gets us so far; it is not the unchallenged emperor of the mind, as many philosophers, until lately, have preferred to think. Most of our decisions in life involve elements pure skill cannot control or account for, chance and emotion among them.

But there is another problem with the Kissinger account. Wei qi has been the game of the elite in China, xiangqi, the game of the Asian hoi-polloi. The West has no comparable opposition. Here, chess is ultimate. Not in China.

Here is what one traditional source has to say on the subject: “Women, children, farmers or herdsmen may grasp the techniques of Xiangqi, but to be good at it is another matter, and even grand Confucian scholars and famous worthies do not dare to lay this claim. Weiqi looks difficult, but is easy. Xiangqi looks easy, but is difficult.”

Kissinger, naturally, picked the Mandarin game, wei qi, over the game of “Women, children, farmers or herdsmen.” That alone, if you care about games, and subscribe to Kissinger’s thesis that they are culturally formative, should arouse suspicions.

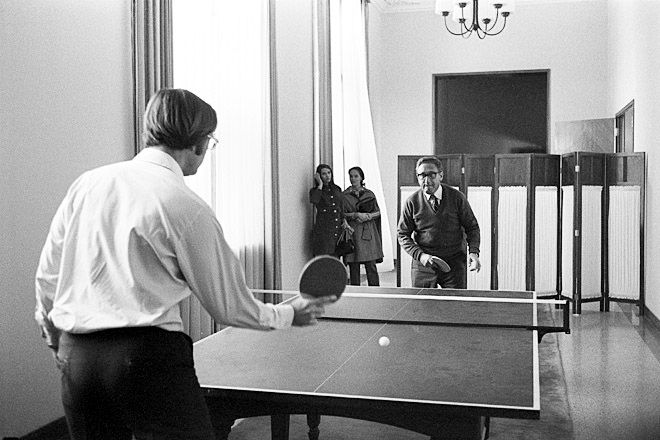

On China boasts photos of Kissinger’s numerous visits to China. In many you see him smiling hugely, brandishing chopsticks alongside the likes of Zhou Enlai. He’s enjoying making history — and the food.

In only one photo do you see him playing any sort of game. It’s not wei qi, nor yet international chess, xiangqi or mahjong. In that one photo, Kissinger, in something close to formal dress, is owlishly hacking away at ping-pong.

Tagged: China, Christopher-Hitchens, Go, Henry Kissinger, On China, Short Fuse, chess, mahjong, stink bug, wei qi

Another truly excellent, wonderfully written piece from HB, but if the “1971” in the following is not a typo, I am missing something here, perhaps some meaning involving philosophical/historical potentiality or….something:

“But 1971 was, in historical terms, an axial year, a year, in other words, when the zeitgeist swiveled. It was the year Al Qaeda leveled the WTC, when President Bush, in response, bombed the Taliban out of power in Afghanistan in a war that seems, a full decade later, almost infinitely far from satisfactory conclusion. “

thank you for pointing this out. i/we meant 2001, not 1971, & will make the fix.