Book Review: Steven Underwood on the New Black Digital Renaissance — and Who Profits from It

By Preston Gralla

What you’ll think of this book will likely rest on what you make of the writer’s definition of Black digital Art.

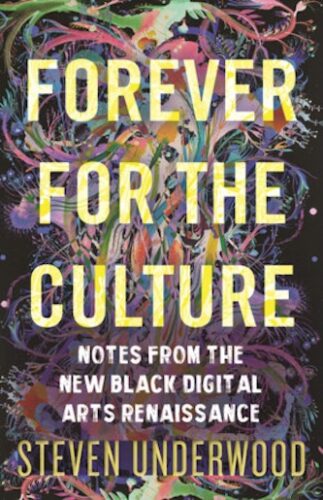

Forever for the Culture: Notes from the New Black Digital Arts Renaissance by Steven Underwood. Beacon Press, 233 pp. Hardcover, $29.95

There’s a long sad history in the United States of white artists stealing or expropriating from Black ones. White creators are acclaimed as innovators and make a mint from assuming the credit, while Black artists struggle to survive. From dance to music, visual arts, fashion design, literature, and more, Black artists often remain unknown or forgotten while those who steal from them profit mightily.

Today, argues Steven Underwood in his slim volume of essays, Forever for the Culture, some of the most significant cultural thefts are taking place in plain sight on the Internet. He asserts that the most alarming instances of appropriation and theft on the Internet is not of copyrighted material, such as songs. Instead, he suggests, the theft is more subtle and less legally actionable, akin to the way the Black dancers who invented and perfected tap dancing received little remuneration, while white performers, including Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, and Gene Kelly, became wealthy and famous.

What Underwood defines as art on the Internet is more amorphous and expansive than a dance style. For him, it is a style of communicating online, a way of building community, taking action, and creating memes.

In the early days of the Internet, he claims, Black culture was walled off in niches and didn’t wield widespread influence. But the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement generated a change, he writes, and Black commentators, creators, and influencers took center stage.

He argues:

Prominent Black creatives diversified their presence across multiple platforms, culminating in domination of the entire digital landscape. Previously viral pop trends of Black communities were insulated and curated by niche websites or largely suppressed by algorithms…

Now, viral pop trends were intermeshed with general issues and concerns. With the rising traction of #BlackLivesMatter and the rejection of the post-racial society as previously lauded by the Obama Administration, Black art captivated social media’s ever-growing platform and artists pushed their voices against the overcoming wave of hatred. It’s truth to say that Black art becomes its most powerful in reflecting the dangers of our existence.

From there, he lays out the way in which what he calls Black digital art flourishes online in what he considers an artistic renaissance, a golden age much like the Harlem Renaissance. He points out the many ways white creators have expropriated that art and profited, while Black creators have not.

What you’ll think of this book will likely rest on what you make of his definition of art:

Digital Black art runs on memes. They are little snapshots into moments, ideas, and feelings that you only get if you are in the know…. They are also currency. Proof of your legitimacy in the world. Recognizing even one makes you a curator. And once Twitter created the culture of the reaction video, a video clip played to season a reply to another person, it turned curators into collectors.

To prove the credibility of Black online commentators and influencers, he even includes how many followers they have on social media — evidence, he believes, of their genuineness and artistic merit.

But I’m not convinced that creating a meme or amassing a huge online following makes one an artist or proves someone’s “legitimacy in the world.” All too often, the reverse is true. The loudest voices online are often the crudest and least sophisticated — the ones you should ignore. Using Underwood’s definition, right-wingers such as Joe Rogan, Megyn Kelly, and others should be considered artists because of their vast online influence and skill at creating Internet memes. But, of course, they’re not.

His misguided definition of art, though, doesn’t contradict his book’s central point: that Black people have influenced the creation of some of the Internet’s most interesting popular culture, and that whites have taken advantage of it and benefited economically from it more than the creators themselves have.

No surprise there, unfortunately: it’s a longtime American tradition.

Preston Gralla has won a Massachusetts Arts Council Fiction Fellowship and had his short stories published in a number of literary magazines, including Michigan Quarterly Review and Pangyrus. His journalism has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, USA Today, and Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, among others, and he’s published nearly 50 books of nonfiction which have been translated into 20 languages.