Book Review: Spotlight on Rock’s Backbone: The “Backbeats” of 15 Drummers

By Tim Jackson

Backbeats is a detailed and informative story. Each profile functions as an entry point into a selective but substantial survey of roughly 75 years of rock history.

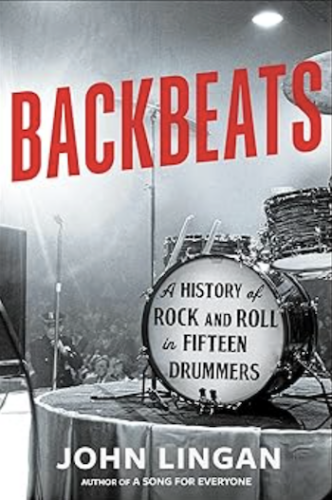

Backbeats: A History of Rock and Roll in Fifteen Drummers by John Lingan. Simon & Schuster, 304 pages, $30.

Drums are the backbone for most forms of pop music — rock and roll, R&B, country, funk, fusion, metal, and hip-hop. They may have started as a timekeeping instrument, but drums have become foundational. That said, approaches to the instrument vary as wildly as rock and roll itself.

For drummers, as for any musician, style is an amalgamation, the end product of influences and mentorships, an appropriation of ideas that reflect time spent with songwriters, producers, and groups. All of these factors are carefully examined in John Lingan’s excellent book Backbeats: A History of Rock and Roll in Fifteen Drummers. The volume contextualizes 15 drummers, each in their historical moment. The author looks at what these drummers listened to, who they admired, and the music they grew up with.

Sam Lay’s career marks the start of a discussion on the blues and folk roots of rock and roll. Lay needed to simplify his jazz chops to meet the needs of nascent rock and roll artists. He eventually moved from roots music to Bob Dylan and the “suburban blues” of the Paul Butterfield Band, while at the same time maintaining his Southern background. He was formidable at emphasizing the second downbeat stroke, allowing the 16th-note grace note just before the downbeat to be softer, which lent the rhythm a distinctive power. One of his lifelong supporters and most dedicated fans was James Osterberg, who eventually gave up the drums to become Iggy Pop.

Hal Blaine, born in 1929, was another highly trained drummer whose command was nurtured by years of nightclub touring. He went on to become one of the most recorded drummers in history, most famously as a member of The Wrecking Crew, the collective of Los Angeles session players who powered hundreds of pop hits in the 1960s. One of his influential collaborations was with producer Phil Spector, who developed what became known as the “Phil Spector beat.” It is a variation on the rock backbeat that drops the first snare hit and places an emphasis on the fourth quarter note, most notably heard in the opening bars of the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby.” (Producer Jack Nitzsche later claimed the pattern was his idea; Blaine, characteristically, said he simply missed the note.)

Al Jackson was a master of straight-ahead, unvarnished simplicity. On the iconic instrumental “Green Onions” by Booker T. and the MGs, Lingan notes, “his groove never moves, he never plays a fill, and he keeps a rigid, almost robotic swing on his huge 20-inch cymbal … unwavering and slightly ahead of the beat.” The author describes how Jackson’s playing “was rarely busier than a resting heartbeat.” Together with his bandmates Booker T., Duck Dunn on bass, and Steve Cropper on guitar (who passed away last December), these musicians became a Stax house band that helped to define the “Memphis Sound.” Jackson backed hits by Otis Redding and anchored classics like “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” and “Soul Man.” Sadly, Jackson was shot by his wife in 1975. He survived but, in a terrible irony, he was shot and killed in his home soon after that attack by assailants who were never found. He was 39.

Ringo Starr, drummer for the Beatles, supplied a quote that says much about his style: “I always felt like it was rats running around the kit if you played jazz and I just liked it solid.” Many of the early drummers in England, such as Ginger Baker, Kenney Jones (Small Faces), and Charlie Watts, were jazz aficionados. Ringo was an exception. He explains it this way: “I’m no good at technical things. I’m your basic offbeat drummer with funny fills … because I’m really a left-handed [person] playing a right-handed kit.” Dave Mattacks, the oft-recorded Brit drummer who lives in the Boston area, explains Ringo’s merit succinctly: Ringo “was never chopping wood. Everything had personality.”

Charlie Watts on drums. Photo: Wiki Common

Charlie Watts, the late drummer for the Rolling Stones, drew on his love of jazz to create a loose style that ebbed and flowed with the Jagger-Richards compositions. Lingan calls it a “refined looseness,” and he makes a key point about the approach when discussing the song “Tumbling Dice”: “… he speeds up here and there, he hits fills slightly off[-]beat, but his playing is always integral and transformative.” Also integral to Watts’s playing is his relaxed approach to the music — his laid-back feel. Even when one of his simple fills may rush, he always returns to the driver’s seat in perfect time.

Kenny Buttrey is a less familiar name, perhaps because of his status as a top Nashville session musician, where drum credits were often anonymous. The chapter begins by discussing Buddy Harman, who was the leading Nashville drummer when Buttrey came on the scene. Harman had notable credits on songs such as the Everly Brothers’ “Bye Bye Love” and the iconic quarter-note backbeat of Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman.” Buttrey, enamored of soul music, “wanted to play like Al Jackson,” and he did so wherever possible within the country genre. His significance came into special focus in his early work on Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, an album that Lingan claims helped establish “the entire genre, the entire notion, of country rock.”

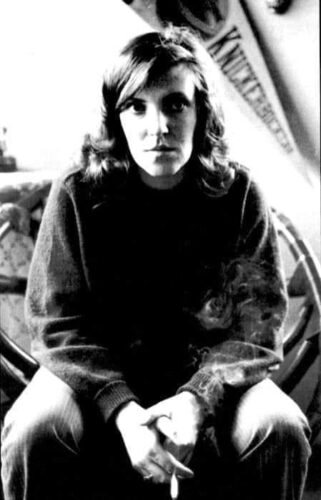

Moe Tucker, drummer of the Velvet Underground. Photo: Facebook

Moe Tucker, who became the drummer for the Velvet Underground, is an interesting choice for a profile because her minimalistic playing could be perceived, at least by some, as being almost naïve. She was tasked with keeping a steady rhythmic hand — to be focused and insistent. She strove to be like her idols Charlie Watts and Clifton James (drummer for Bo Diddley), each of whom “in the storm of their bands … kept things danceable and light while [the] showman improvised and spiraled off.” When the music went wild, Tucker’s playing gave the audience something to hold onto. She says her approach was simple: “This is a song. There is the beat.” She was inspirational because of her loyalty to the “jackhammer beat,” and as a model for other women who would later take up the drum chair.

Clyde Stubblefield played a very different role as a percussionist. His work with James Brown made use of his sophisticated sense of rhythm and sharp syncopation. He sounded, as Lingan puts it, “like he was playing hide-and-seek with the snare.” Brown’s music emphasized the repetition of intricate rhythmic patterns — at the time, it was a shift in how popular music was structured and performed. Stubblefield was a master of holding a single groove steady for long stretches. He also created singular, iconic beat patterns on songs like “Cold Sweat” and “Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud.” His beat on “Funky Drummer” became one of the most sampled grooves in the history of recorded music. Central to his style was a gift for subtly articulated ghost notes, accents that added depth and elasticity to the main groove, without ever breaking the latter’s spell.

John Bonham was a musician whose singular style perfectly matched the needs of his band. Led Zeppelin could not have existed in the same form without him, just as The Who would have been unthinkable without Keith Moon. Both men were virtuosos whose excesses ultimately led to early deaths. From the opening cut on Zeppelin’s debut album, Bonham’s skill and individuality were unmistakable. His 32nd-note flutter kicks on the introduction to “Good Times Bad Times” were astonishing at the time. The author notes, “Hendrix was agog at the man’s right foot.” Lingan goes further, arguing that Bonham’s massive sound marked the moment “when rock and roll drumming became rock drumming.” That subtle parsing underlines an essential point; with Bonham came a thicker, heavier drumming style that managed to retain great dexterity.

Bernard “Pretty” Purdie represents a different kind of drummer altogether. His legacy is built on precision, consistency, and feel, a sound nurtured over decades of session work. Purdie has claimed to have played on some 4,000 recordings, a figure that may be exaggerated. He has also, controversially, asserted that he replaced drum parts originally played by Ringo Starr. He possesses, by his own admission, a considerable ego. He once hung a sign in his studio that read: “You’ve Did It Again Pretty Purdie Hit Maker.” Still, bravado aside, listening to a Purdie track is a master class in the art of controlled elegance. Thousands of drummers have tried to replicate his grooves, particularly the drum break on Aretha Franklin’s 1971 hit “Rock Steady,” one of the most sampled rhythms in popular music.

Earl Hudson of the band Bad Brains is notable for breaking the expectation that punk music was a British product, as exemplified by the Clash and the Sex Pistols. He could make reggae beats swing, and also had the power, speed, and energy to match the band’s most confrontational songs. Bad Brains’ music may have had more attitude than it did aesthetic value, but that evaluation may be a matter of taste. Hudson has influenced such drummers as Dave Grohl, Will Calhoun of Living Colour, and Chad Smith of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Influenced by Hudson, they brought virtuosity to the speed and mad energy of punk.

Author John Lingan. Photo: Daniel Stack

Tony Thompson will be a revelation to many. His playing served as the rhythmic architecture for Robert Palmer’s “Simply Irresistible” and “Addicted to Love.” His drums sounded like the pounding engine of some colossal machine. He powered the disco hits of the band Chic, including “Le Freak” and “Everybody Dance,” as well as Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” and “Material Girl.” One of Thompson’s wildest grooves comes at the opening of Diana Ross’s disco hit “I’m Coming Out,” where he plays an extended stuttering drum entrance before settling into a dynamic straight-ahead dance beat. To my mind, Thompson may have anticipated the advent of drum machines, given his precise, pared-down grooves. Still, his playing always feels deeply human.

Dave Lombardo’s playing is built on speed and ferocity, far from the grounded dance precision of Tony Thompson. As drummer for Anthrax and, most famously, Slayer, Lombardo helped define thrash metal’s kinetic edge. The book highlights “Angel of Death,” Slayer’s notorious track about Josef Mengele. The tune is propelled by Lombardo’s relentless double-bass attack, which drives 16th-notes at roughly 250 beats per minute near the song’s climax, more than double the tempo of a brisk disco groove. Yet Lombardo is more than a speed merchant. Beneath the velocity lies control, phrasing, and an ability to shape complex rhythmic patterns rather than merely sustain impressive endurance.

Dave Grohl represents a different model of percussive influence. One of the most commercially successful drummers of his generation, Grohl expanded beyond the kit to become a guitarist, frontman, producer, writer, and filmmaker. His projects include the documentary Sound City (2013), the HBO series Sonic Highways, and the bestselling memoir The Storyteller: Tales of Life and Music. As a drummer, Grohl’s style is direct and muscular — hard-hitting, clean, and anchored by a deep pocket. The chapter situates Grohl’s career within the arc of alternative rock’s ascent to the mainstream.

Questlove offers yet another template for the modern drummer. As the driving force behind The Roots, widely known as the house band on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, he has balanced performance with scholarship and production skills. He directed and produced Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), a landmark documentary reclaiming the Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969. His work integrates technology and tradition, layering programmed rhythm onto human grooves. His innovations are subtle but far-reaching. With Questlove, the drummer is no longer merely the engine of the band, but its historian, curator, and cultural translator.

Backbeats: A History of Rock and Roll in Fifteen Drummers delivers on its ambitious premise. The narrative is detailed and informative, each profile functioning as an entry point into a selective but substantial survey of roughly 75 years of rock history. Lingan situates stylistic developments within longer traditions, tracing many rhythmic choices back to their early foundations in jazz. He also maintains a deliberate balance between Black and white drummers, power players and groove specialists, traditionalists and formal innovators. The result is a book that values more than technical superiority but appreciates drummers who represent genres and/or expand pop music’s rhythmic vocabulary.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter-skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story. And two short films: Joan Walsh Anglund: Life in Story and Poem and The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

A nice piece, Tim, an ace rock drummer’s keen, loving appreciation for those who drummed before.

Thank you, Tim, for this review. I would never have been aware of John Lingan’s book. Your concise review really sets the interest in each of these drummers (God Damn Drummers never get their due despite the fact they are everything to rock).

I’m surprised at the lack of any of the prog rock drummers. I would have been interested in a comparison between their approach and, say, John Bonham.

Great review, Tim, breaking down the book’s 15 drummers into tight summaries. The author’s choices seem quite smart and diverse, though indeed a bit unusual in not including a prog-rock icon like Bill Bruford or Neil Peart. An interesting read.

My feeling about that is that the best “prog rock” drummers are also products of the arrangements and music of the bands that required great technical skill , though the playing itself didn’t head drumming in new directions. It’s the author’s choice, but it inevitably such an inclusion might pit one percussion virtuoso against another. It’s hard rate even drummers like Mike Portnoy or Terry Bozzio on a scale of influence.

Thanks for including them all. A treat!

Interesting review, Tim. Makes me want to know more…