Sundance Fest’s Last Winter in Utah — Docs on a Small Town Newspaper, the Attack on Salman Rushdie, and Public Access TV

By David D’Arcy

A trio of illuminating documentaries, their topics ranging from the struggles of a local newspaper to the days of public access cable television in New York City.

The Sundance Film Festival has left Utah after over three decades, and after the death of its founder, Robert Redford. More on that later.

A still from Sharon Liese’s Seized. Photo: courtesy of Sundance Institute and Jackson Montemayor

As for the films this year, a documentary from Kansas reminded us that, to paraphrase Flaubert loosely, to find corruption, you just have to look at a place long enough.

Seized, by director Sharon Liese, which premiered at Sundance, picks up a trail of misdeeds that becomes more topical every time ICE (or any other Federal agency) arrests a reporter or threatens to, or justifies violence on the basis of false information. Such was the case of the Marion County Record in Marion, Kansas (pop. 1,900), a small-town newspaper northeast of Wichita, which had its computers, phones, and files seized in August 2023.

The search, violating a range of constitutional guarantees, came after the newspaper revealed that a restaurant owner seeking a liquor license turned out to have had a drunk-driving history. The woman happened to be an intimate of the town police chief, who demanded the search and seizure at the newspaper along with same at the home of its editor/owner. That editor, Eric Meyer, lived in the home with the paper’s former editor, his mother of 98. She cursed at local cops when they stormed into her house, and died after the heated exchange. If that isn’t the setup for a story, what is?

It turned out that the newspaper had not violated any laws in seeking and finding confirmation of the drunk-driving offenses. The house search was illegal. It also turned out that the judge who issued the warrant for the search and seizure had not read the document.

Not to be confused with a 2020 action-thriller of the same title, the plot of Seized is symptomatic of how journalism is under attack well beyond the Trump administration. Local newspapers are struggling to stay in business. Even the Washington Post, owned by the zillionaire Jeff Bezos, laid off 300 staff — after Bezos spent some $80 million producing and distributing the vanity documentary Melania. (I still haven’t seen that film. I’m waiting for the subtitled version.)

Without local coverage from the Record, which published the details of all the crimes in town, corruption in Marion, led by the now-departed police chief, could have continued unremarked and undisturbed. It’s odd that the Record’s critics interviewed in the film don’t seem embarrassed by the newspaper’s revelations. Maybe a small town with secrets didn’t mind getting all that attention. Press scrutiny sometimes brings in more money than tourism.

Editor Meyer is on hand to remind journalists — and the audience – that the journalism has some of the same challenges wherever you are, “Everyone tries to control the message,” the avuncular editor tells a young journalist who traveled from New York to begin his career at the Record, “They view what we do as intrusive. We have to get past that.”

As much as some of the townspeople in Marion claim to hate the Record, they have gotten past that, too. “I got a buddy. He won’t buy the paper, but he reads his wife’s,” says a local barber.

There was talk at Sundance of Seized being remade into a scripted drama — or would the ham-fisted police intimidation make it a comedy? — featuring Tom Hanks as Meyer. That sounds about right, with a young star as the cub reporter, fresh from Manhattan, in a strange land.

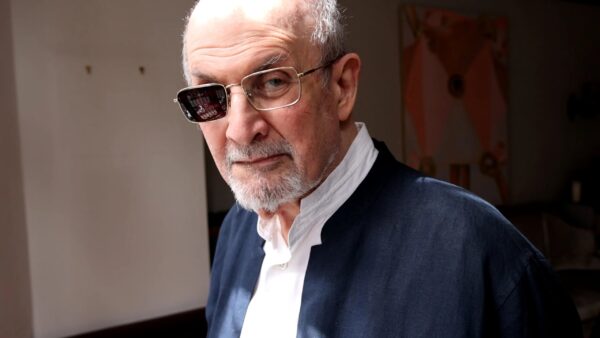

Salman Rushdie in Alex Gibney’s Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie. Photo: courtesy of Sundance Institute and Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Also at Sundance was Knife, Alex Gibney’s documentary about the bloody attack that almost killed Salman Rushdie in 2022 and the grueling recovery time through which the writer came to terms with the ordeal. Time enough for the book, Knife: Meditations on an Attempted Murder, on which the film is based.

Rushdie’s story is dramatic in its account of the attack, which took place when the author was being interviewed onstage at the Chautauqua Institute. The attacker, referred to as A in the book, was a young man born into a Lebanese Shiite family, raised in a bland New Jersey town near the George Washington Bridge. He came under the influence of Hezbollah’s militant brand of Islam. Unrepentant after being convicted, he is now serving a sentence of 25 years. Note that the charge was attempted murder. The would-be killer is lucky, if that’s the right word, lucky that Rushdie survived.

And Rushdie himself is indeed fortunate, if that’s the right understatement. As we hear a painstaking description of his wounds, we learn about the many ways that he could have died. A doctor thought he was cheering up Rushdie when he told him: “You’re lucky that the man who attacked you had no idea how to kill a man with a knife.” He still came close.

Much of the writer’s painful process of recovery is discussed in uncomfortable anatomical detail. Lots and lots of talk. What’s different about Alex Gibney’s approach is what we are given to see. There is plenty of archival footage. Cameras were set up in Chautauqua, as they would be for the visit of any celebrity. We watch as Hadi Matar, 24, walks onto the stage in the airy arena, and then stabs Rushdie repeatedly. At first the others on the stage seem paralyzed; but finally they subdue him.

The footage of Rushdie’s recovery follows, as tubes are placed in and out of him, and he finally loses an eye. You won’t see him without an eye-patch these days. Even after all that misery, the writer is pleased to be alive and to be with his devoted young wife, Rachel Eliza Griffiths. He finds the energy to conduct an aggressive interrogation of his attacker — his version of the attacker — and voices both sides of that inquest, as he did in the book.

There are moments in Knife when you feel that you’ve witnessed a miracle, given the ferocity of the attack, and a man years later who can walk and tell jokes and do all sorts of other things. Miracle or not, security at the theater in gun-toting Utah — where I saw Knife — was tight and deliberately visible. It was one of the rare places in Utah (a constitutional carry state) where people were discouraged from bringing guns.

Knife is an engaging but wrenching film. It’s not entertainment; it’s exhausting, often a challenge to watch, as it should be. Rushdie can come off as transcendent in his recovery, yet he still has to struggle with the same wounded body. Gibney makes sure you never lose sight of that.

A still from David Shadrack Smith’s Public Access. Photo: courtesy of Sundance Institute and David Shadrack Smith

As always, Sundance exhumed forgotten audiovisual adventures. In Public Access, the feature debut of David Shadrack Smith, that meant going back to the days of public access cable television in New York City, an open-mike salon des refusés of people who wanted to be seen and heard in cable’s early days.

Putting this hodge-lodge of opinionators on television was an inevitable step toward free expression back then, or at least it was what people who’d been denied a voice on television did at the time. Given all the footage that Shadrack had to go through, the editing job must have been like cleaning out the Augean Stables, only longer.

During that period, I was producing and hosting programs on WBAI, a listener-supported radio station in New York. There was plenty of talent at the station, but production was time-consuming and expensive. The best programs were usually live, with hosts who knew the subjects they were discussing and knew how to use the medium of radio. On public access television, everyone was new to the medium. In most cases, the shows were as good or as bad as the personalities on camera — i.e., not always good.

It was a crazy mix, and it’s good that so much if it has been preserved. Public Access resurrects some of those early personalities. Al Goldstein of Screw magazine was one, with the program Midnight Blue, which played for years. Ugly George, a man with a camera on his shoulder who accosted women on the street and asked them to pose for him, was inescapable. Someone will have to explain to me why he was never arrested. Robin Byrd, always clad in a crocheted bikini, was another. All of these hosts are reminders that the commitment to free speech on early cable was kept alive by pornography. Gay programs, mostly male but not porn, were also part of the offerings.

I was struck by the paucity of music that ended up on public access, especially given how much no-budget music, punk especially, was happening downtown. The musicians were interviewed, which is a cheap use of the format — cheaper than recording music performances, since live music would have cost too much. Soon MTV filled that cultural space — mostly with corporate product — to the detriment of the medium, but to the benefit of the bottom line. Filmmakers, once attracted to bare-boned TV, turned to no-budget feature films, leaving the tube behind. Or they just ground out music videos.

Public Access‘s vaudeville of 10-cent political forums and attention-seeking personalities feels like a missed opportunity. Local cable TV could have been something much better. TV would rise again, but as a world of sit-coms that made a profit by bringing in young audiences. We are left with films like Public Access to see the efforts to make a different, more subversive, kind of TV.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: "Knife", "Public Access", "Seized", Alex Gibney, Salman-Rushdie