Poetry Review: “A Violence” from Within — Paula Bohince’s Switchblade Lyricism

By Michael Londra

You can almost hear the volume whispering in your ear, Be like lichen. Traumatic grief, political tyranny, and environmental catastrophe are not irreversible.

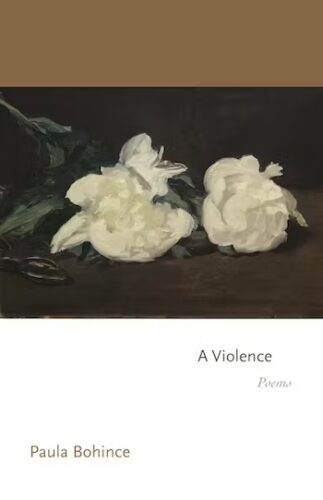

A Violence: Poems by Paula Bohince. Princeton University Press, 88pp, $17.95.

In an 1852 letter to poet Louise Colet, Gustave Flaubert justified the painstaking process that eventually produced the novelMadame Bovary: “With my burned hand, I have earned the right to speak about the nature of fire.” As a nineteenth-century proponent of literary realism, Flaubert championed writing derived from personal experience, though meticulously reshaped by rigorous technique. Influencing Marcel Proust and James Joyce, Flaubert’s famous obsession with linguistic exactitude—“le mot juste”—stemmed from his belief that “what is beautiful is moral;” or, as he put it in a missive to George Sand: “aesthetics is a higher justice.”

In an 1852 letter to poet Louise Colet, Gustave Flaubert justified the painstaking process that eventually produced the novelMadame Bovary: “With my burned hand, I have earned the right to speak about the nature of fire.” As a nineteenth-century proponent of literary realism, Flaubert championed writing derived from personal experience, though meticulously reshaped by rigorous technique. Influencing Marcel Proust and James Joyce, Flaubert’s famous obsession with linguistic exactitude—“le mot juste”—stemmed from his belief that “what is beautiful is moral;” or, as he put it in a missive to George Sand: “aesthetics is a higher justice.”

Indeed, Flaubert’s aphorism “l’esthétique est une justice supériure” can be found in the posthumously published notebooks of Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet Wallace Stevens. Although he preferred Stendhal, Stevens still considered Flaubert a “point of reference for the artist.” However, in Stevens’ 1942 essay “The Noble Rider and the Sounds of Words,” he attempted to surpass the example of Flaubert. Insisting that sonorous language itself stood as a public good, Stevens argued literature could do more than reflect reality in the Flaubertian manner—poetry can also fight the good fight against the psychic oppression of the real. Poets were “noble riders” wielding “the sounds of words” on the side of society’s wellbeing, enforcing Flaubert’s “higher justice” through poetic invention as a means to reshape the perceptual acuity of readers. From this perspective, poetry was not just a hoity-toity plaything for the ivory tower crowd. According to Stevens, verse was about the “imagination pressing back against the pressure of reality,” a “violence from within that protects us from a violence without.”

Taking the enigmatic title of her collection from this line, Paula Bohince’s fourth book of poetry, A Violence, puts Stevens’ assertive vision to work. She brandishes her poems like a rhetorical knife slicing into reality, at one point battling against trauma (“on the make-believe dance- / floor, trying to turn despair into a party,” from “Among Barmaids”). While many contemporary poets fetishize the virtues of “ordinary speech,” Bohince’s treatment of language is closer to such stylish precursors as Robert Lowell, Seamus Heaney, Jorie Graham, Sharon Olds, and Henri Cole. A few examples: “A grief of salt over a deer’s last leap, collapse of / that crystal palace over the fatal synaptic blink” (“Fruitless”); “Ache of un-stabled horses at sundown, winter- / berry turned up to ten. Escaping the tent’s nylon into / the forest’s first breath” (“Afterglow”); “Oculus giving up Andromeda, / pulse of variegated phlox, // fog-drenched, a virginal shepherd on a lamb / watch, terrine of fowl and gilled // chanterelles” (“Explicit, 1976”).

The volume’s sixteenth poem (of fifty-four), “Lamentation Once Again,” reckons with the legacy of familial abuse: “Though I began as shudder through the father, / uncurling terror, growing toward light, finally sleepwalking / as shock-riddled bafflement, leaning against / a vacancy. Though I was silence and rise / and deliverance through icy rinse to arrive and be stood still as the dead / in the blizzard’s deeps, Frostian echoes / and presence of wedding bullets sent up in spring / fallen back as wintery confetti.” Bohince’s sumptuously mysterious words suggest foreboding far more powerfully than if she has explicitly spelled out the danger in plain-spoken particulars. Note how she responds, with subtlety, to Stevens’ ask for metrical violence.

Poet Paula Bohince. Photo: Princeton University Press

Moving from one existential state to another in poem after poem, A Violence dramatizes how any kind of subjective transfiguration is necessarily brutal. To gain, as the cliché goes, there must be pain. Bohince is crafting for herself a new way to live on the page in what feels like real time; and that creative process reflects the excruciating crucible of childbirth. To be sure, bringing forth new life in any form while sustaining that level of intensity is a formidable challenge. Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño perhaps best described the logic of righting (“rewriting”) earlier traumatic wrongs in this way: “Violence is like poetry…you can’t change the path of a switchblade / nor the image of dusk.” In this sense, Bohince in A Violence uses the imagination as a choral switchblade — in two ways. It is an instrument of self-defense that serves as a kind of makeshift stylus.

“The Skunk” is inspired by a found image, gleaned from an article published in a regional newspaper—local to the part of the Appalachian Mountains in Western Pennsylvania where Bohince spent her childhood. The poem begins with a blaze: “In the smudgy Local section, a fire / living underground for half a century will be put out. / An ember once thrown into a mine shaft / within a mile of my house, some midnight by a tired / anonymous, that person surely dead now, the consequence / roaming since, low-lit at times like a candle, other years ghost-vigorous.” Bohince seizes on this real-world event to fire up the reader’s imagination. Is there a better metaphor for repressed memories than that of a subterranean flame? Bohince takes the news report and connects it with her own experience of EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing): “I sleep while the fire seethes…Imagine the ideal mother, the therapist said. He shifted when I spoke an octave higher, when I cried out for / the mother’s animal body and made a grotesque motion with my face, / meaning I wanted to burrow against it.”

According to the EMDR Institute website, this treatment is a “psychotherapy…designed to alleviate the distress associated with traumatic memories.” The approach is facilitated, in part, by “focusing on…[t]herapist directed lateral eye-movements.” Similar to the substances enlisted to flood an Appalachian coal mine, the poet during EMDR is guided toward confronting something that is perceived as deadly: “digging into the past, I work, I collapse, I lie / on a vibrating mat meant to mimic / the maternal embrace.” An unanticipated (and harrowing) vision of the speaker’s mother materializes: “Once, she appeared as Meryl Streep, in the field, / where my own mother burned off her rage, and I was made to / follow, less than a dog on a leash. In the therapist’s / office, among the mashed stalks, breathless, sweat, / Meryl said to me, This sucks.” Suddenly, the tormenting mother’s presence retreats: “Tender skunk-mother, I love you, receding / in your backward shuffle.” Resolving her angst through the dreamlike apparition of Streep, the poet fuses the solace of her emotional catharsis with the smothering of the underground fire: “the hellhole soon to be filled / with spring water or some alkaline compound: / balm of man, cold compassion.”

Bohince’s verse draws on a wide gamut of allusions. Name-checks from her “mind’s anthology” (“At Thirty”) arrive thick and fast: syrupy ’80s Prog Rock balladeers Styx; Virginia Woolf and Emily Dickinson; painters Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, and Velázquez; the Hip Hop dance style known as popping and locking; Irish Gaelic; Cleopatra; and classic flicks such as Breakfast at Tiffany’s and The Conversation.

Given the complex cultural heritage of Appalachia, Bohince’s mixture of sacred and secular is natural. She has traveled extensively around America and overseas — trips touched on in “Escape to Fiji;” “Among Barmaids,” which set in Ireland; and “A Brief History of the Cocktail,” which gives us the alliterative adrenaline of “the sail of a Spitfire / cresting a hill in San Francisco, fin against sunset.” But Bohince’s Appalachian roots run deep — the sound of a gospel-tinged, High Lonesome bluegrass mandolin rings through her stanzas. The story of her family’s farm in “Accordion Music,” its inheritance eventually lost, receives a lyrical treatment that merges sorrow with spiritual uplift. In this poem, Bohince shifts her rhetorical stance, for once speaking in the collective voice of her ancestors. Her verse could be set to a Bill Monroe riff: “The homestead was the whole of their wealth…we were ignorant / as sunshine, illiterate…a melody guided us.”

Another Appalachian heirloom on display is the beauty of its landscape. Bohince communes with every vibrant, non-human inhabitant of nature on its own terms. All creatures are her comrades—bluebirds, swans, Java sparrows, bats, bees, flowers, horses, cats, donkeys, rabbits, elk, even a bull shark. In “The Green,” the poet sings of the endemic color of the bucolic woodlands of her youth: “There is green, there is the green / of childhood.” A series of associations follow suit; green is more than a color, it is a universe she must unpack: “the single / green pane smearing the backward // glare and breakneck present…the green thrall of time.” Still, while beautiful, green is freighted with negative meanings as well: it can also signify pain. Bohince acknowledges that the source of her identity—her love of the mountainous emerald realm—is also the “cause” of the wound that continues to haunt her: “I’ll return, surround of walnut hulls, / a tabled dollar, I’ve held on to / childishness longer than most, green loss, / the green, Oh God, it is the cause.”

A tree covered with leafy foliose lichens and shrubby fruticose lichens. Photo: Wikimedia

These verses articulate the violence that shadows every life, our knowledge of our fragility and mortality. For Bohince, poetry magically transmutes suffering into inspiration—restoring our spirits, shoring us up against apathy and demoralization. Picking up Bolaño’s switchblade with Flaubert’s burned hand, Bohince’s verse asks us to consider an unlikely model for resilience and fortitude: the lichen.

The British Lichen Society describes lichens as a hybrid life form with a knack for survival: “Lichens are made up of two or more closely interacting organisms,” specifically a mutually beneficial “symbiotic association between a fungus and algae.” Google thumbnails confirm that impressive strength: lichen grow in all kinds of environments, from deserts to forests, on bark or over rock face, as sprouting shrub or crust.

That survival instinct directly links with gauging climate change. Lichen are the canary in the coal mine, an index to the declining ecological health of our planet. Wherever lichen die out, it doesn’t bode well for the broader ecosystem. Bohince envisions poetry as a living entity as well, a lichen nurturing its environment. Highly adaptive, the poet is a symbiont who reciprocally nurtures the community that fostered her. And her welfare, in return, can be considered a key indicator of the health of her society.

In that sense, Bohince’s poems—like lichen—grow out of civic turmoil. She insists in A Violence on shared empathy and solidarity, not just with our immediate neighbors, but with people around the world. You can almost hear the volume whispering in your ear, Be like lichen. Traumatic grief, political tyranny, and environmental catastrophe are not irreversible. In A Violence, Bohince uses her imagination to repel that which seeks to destroy us. Her poems are switchblades of beauty, parrying and counter-attacking at once. We can make a difference. It’s not too late. Only poetry refutes death: “Instinct trembles / within the lichens’ plurals, / arterial on rock, selves scribbling, / like us, each awe.”

Michael Londra—poet, fiction writer, critic—talks New York writers in the YouTube indie doc Only the Dead Know Brooklyn (dir. Barbara Glasser, 2022). His poetry has been translated into Chinese by poet-scholar Yongbo Ma. Two of his Asian Review of Books contributions have been named to the publication’s list of Highlights of the Year for 2024 and 2025. “Life in a State of Sparkle—The Writings of David Shapiro” from The Arts Fuse was selected for the Best American Poetry blog. “Time is the Fire,” the prologue to his soon-completed Delmore&Lou: A Novel of Delmore Schwartz and Lou Reed, appears in DarkWinter Literary Magazine. He can also be found in Restless Messengers, The Fortnightly Review, spoKe, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, and The Blue Mountain Review, among others. Born in New York City, he lives in Manhattan.

Tagged: "A Violence", "A Violence: Poems", Paula Bohince, contemporary American poetry