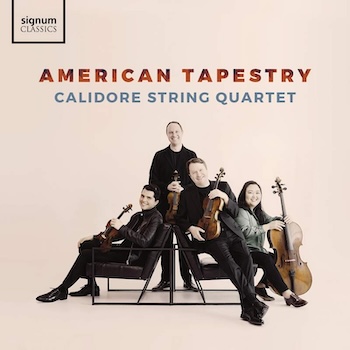

Classical Album Review: Calidore Quartet’s “American Tapestry”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

If there’s anything the U.S. needs in 2026, it’s a recovery of Lincolnesque values—resolve, common sense, understanding, and charity. If such a renewal can get some impetus and sense of direction from a new recording, so much the better.

Given the climate of violence, anger, and uncertainty coursing through the United States these last months, 2026 is shaping up to be a strange year for celebrating the country’s 250th birthday. But while certain of the challenges facing the nation are unique to our moment in time, a tenor of social unrest has been the rule, not the exception, throughout American history.

Given the climate of violence, anger, and uncertainty coursing through the United States these last months, 2026 is shaping up to be a strange year for celebrating the country’s 250th birthday. But while certain of the challenges facing the nation are unique to our moment in time, a tenor of social unrest has been the rule, not the exception, throughout American history.

For their latest release, the Calidore Quartet has mined—albeit somewhat obliquely—a bit of that experience. American Tapestry, their new collection of music for string quartet written between 1935 and 2012, may, on the surface, sound more restrained than what the day calls for. But at its best, the program refocuses attention from the dizzying overload of daily offenses and points, instead, to a bigger context.

The recording’s oldest item is Samuel Barber’s B-minor String Quartet. Written at the height of the Great Depression, this is music for which it is exceedingly difficult to attach an extramusical program. Nevertheless, a taut urgency marks its driving first movement, while the central Adagio has taken on a life of its own as a staple of national mourning.

Here, the Calidores manage a performance of the latter that’s anything but overwrought. This Adagio is well directed but also marked by a natural sense of pathos and fervency. The preceding section is similarly alive to the music’s contrasts of tension and repose. Only the short finale doesn’t quite come off, though the fault there lies with the composer (though he tried, Barber never managed to write a satisfactory last movement).

Erich Wolfgang Korngold was somewhat more successful with the rondo-finale of his String Quartet No. 3—but just barely. Written in 1945, the work channels the composer’s depression at the world situation (he had been working in Hollywood when Germany annexed his native Austria in 1938 and became a naturalized American citizen in 1943) and his relief at Hitler’s ultimate defeat.

As such, it offers a fascinating deconstruction of Korngold’s lush, late-Romantic style. The writing throughout is impassioned and tightly motivic. Echoes of film scores emerge here and there, as do clear nods to Mahler (especially in the third movement) and idealized reminiscences of the Vienna of his youth.

At the same time, the Quartet is full of freshly dissonant writing. Sonorities that suggest a close kinship with Webern and Schoenberg abound. The Allegro molto sounds like a Beethoven scherzo making a mad dash through a hall of funhouse mirrors. For all its touching warmth, the Sostenuto often seems to be on the verge of an emotional breakdown, its textures holding together by the skin of their teeth (as it were).

In this movement, especially, the Calidores are in fine form, articulations impeccably unified, the music’s transitions (and dynamics) handled with deep feeling and understanding. Their synchronicity also impresses in the concluding Allegro con fuoco: that section’s grace notes and turns are conspicuously fresh. While Korngold’s writing here stretches his thematic invention to the breaking point, there’s an ebullience to the performance that charms.

Wynton Marsalis is another composer who likes to push musical envelopes, as he does in three movements from his String Quartet No. 1, At the Octoroon Balls. Drawing from all over the stylistic spectrum, the effort alludes both to the composer’s youth in New Orleans and, as a program note puts it, “American Creole contradictions and compromises.”

How much of the latter comes across in this reading is an open question, though there’s no denying the groovy allure of “Creole Contradanzas” and the soulful warmth of much of “Many Gone.” “Hellbound Highball,” on the other hand, is a spiky, dissonant hoedown that runs a bit long—though its bent notes and bluesy touches are plenty evocative of a diabolical jam session.

Filling out the album is a new arrangement of “With Malice Towards None” from John Williams’ score to Lincoln. If the number’s open, Coplandesque harmonies suggest a certain naïveté, they also call to mind the clarity of purpose and moral backbone the Great Commoner exhibited more than most. In fact, if there’s anything the U.S. needs in 2026, it’s a recovery of Lincolnesque values—resolve, common sense, understanding, and charity. If such a renewal can gain some impetus or sense of direction from a new recording, so much the better.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.