Book Review: Olga Tokarczuk’s “House of Day, House of Night” — A Demanding But Rewarding Reverie

By Clea Simon

House of Day, House of Night is not an easy read, but for those with the stamina, it is a rewarding one, inviting us to savor its reclusive, succulent insides.

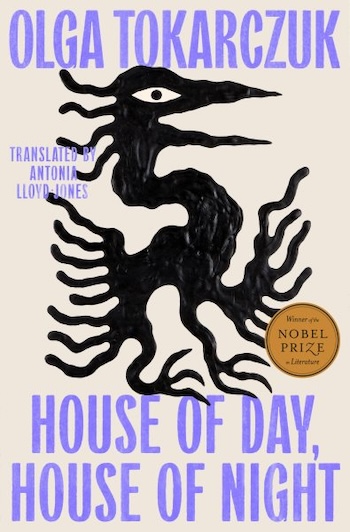

House of Day, House of Night by Olga Tokarczuk. Riverhead Books, $28, 336 pp.

A saint, a werewolf, a corpse without a country, and an old woman named Marta who grows rhubarb and makes wigs and theorizes about the souls of those around her. These are only a few among the recurring characters in Olga Tokarczuk’s House of Day, House of Night, a 1998 novel that has now been translated into English by Antonia Lloyd-Jones.

A saint, a werewolf, a corpse without a country, and an old woman named Marta who grows rhubarb and makes wigs and theorizes about the souls of those around her. These are only a few among the recurring characters in Olga Tokarczuk’s House of Day, House of Night, a 1998 novel that has now been translated into English by Antonia Lloyd-Jones.

Pitched as a “constellation novel,” in the vein of the Nobel laureate’s 2007 International Booker Prize-winning Flight, House of Day, House of Night is not so much one continuous narrative as a series of vignettes, some featuring recurring characters, like Saint Kummernis, who grows Jesus’ face – including beard – to protect her virginity, or poor Peter Dieter, who dies on the Czech-Polish border and who is continually shoved from one side to the other by border guards who don’t want to deal with a corpse. Lightly framing these episodes are the unnamed first-person narrator’s interactions with her neighbor Marta, whose analyses of the life around her swing from the earthy (mushrooms, death) to the spiritual.

More than a string of narratives, however, House of Day is a story of themes. Color – especially white – is one such motif that pops up frequently, whether in a description of the “smooth white” breasts of Kummernis, the nameless white roses “that smell like wine that’s gone sour, or rotting apples”, or the snow, “a great white parasite” that lasts “until April.” Borders also figure heavily in the novel, which is largely set in Silesia, a disputed region that had been German through World War II and then given to Poland, but where German tourists still come to visit their old homes. These borders also include those between edible and poisonous mushrooms (recipes for both are included), as well as between the narrator and the fungi: “If I weren’t a person, I’d be a mushroom. An indifferent, insensitive mushroom with a cold, slimy skin, hard and soft all at once,” she announces in a section that ends on another favorite theme: death. “What is death, I would think – the only thing they can do to you is tear you from the ground, slice you up, fry you and eat you.”

But the biggest and most frequently crossed border in the book is that between reality and fantasy. Often this line is erased by dreams. And while the first-person narrator’s illusions are labelled as such – “I dreamed I am able to enter people through their mouths” – others are less clear or are taken (and presented) as reality. In fact, as the title suggests, much of House of Day, House of Night seems to exist in an oneiric state, complete with its own oddly skewed logic. When Marta tells the narrator about “all sorts of creatures God had forgotten to create,” the salient point of the exchange isn’t Marta’s fantastical imagination but that, referring to the creature that she “missed most… the large, sluggish creature that sits at the crossroads at night,” “[s]he didn’t say what it was called.” In this, as in her vivid imagery, Tokarczuk recalls the writing of surrealist Leonora Carrington, in which the impossible is treated quite matter-of-factly as quotidian reality.

Whether the scene is believable as grounded actuality or not, the writing (as in all of Tokarczuk’s books) is gorgeous in its specificity. The classics teacher who (perhaps) suffers from lycanthropy watches his students in dismay as “[a]ll the meaning came dribbling out of them like poppyseed from a burst bag.” Discussing the person who translated the German place names into Polish, the narrator notes: “Words grow on things, and only then are they ripe in meaning… Only then can you play with them like a ripe apple, sniff them and taste them, lick their surface before snapping them in half and inspecting their reclusive, succulent insides.”

The downside of all of these gorgeous bits is that their connections remain tenuous, which asks that the reader hold the entirety of the book in her head. Unless read in one fell swoop, the jumps are distracting, the lack of continuity an obstacle. House of Day, House of Night is not an easy read, but for those with the stamina, it is a rewarding one, inviting us to savor its reclusive, succulent insides.

Clea Simon is a Somerville resident whose latest novel is The Cat’s Eye Charm (Level Best Books).

Am reading it now and find your review illuminating. Thanks!

Thanks, Peter. Curious to hear what you think. – Clea

I agree with you that the writing is mostly superb. But I prefer her more rigorously narrative works, like The Books of Jacob and the Drive Your Plows over the Bones of the Dead.

same here

Late to reading this illuminating review. A rich new subsubgenre? novels sprung from disputed borderlands. Handke’s Serbian rage comes to mind, and Eva Menasse’s prize-winning Darkenbloom (reviewed here Jan 2025) set on the Austrian-Hungarian border.