Book Review: “Old Man Evil” — Vincent Czyz’s Cartography of Conscience

By Jeffrey Kahrs

In this collection, Vincent Czyz’s imagination covers extensive geographic and historical territory, creating maps whose borders are drawn with the vigor of a nuanced moral temperament.

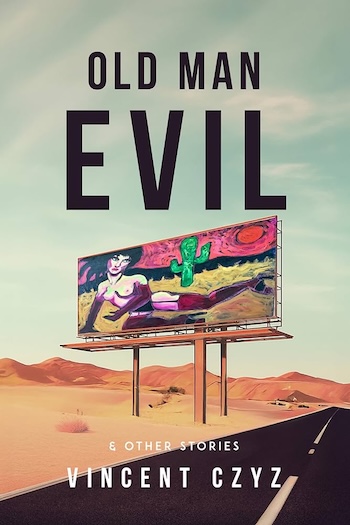

Old Man Evil by Vincent Czyz. Running Wild Press, 286 pages, 21.99 (paperback)

by Vincent Czyz. Running Wild Press, 286 pages, 21.99 (paperback)

When I was a starry-eyed freshman, I had the bright idea of taking a class from Gregory Bateson, the great English polymath. I was often confused, having bitten off more than I could intellectually chew, but Bateson made sure everyone in the class understood Alfred Korzybski’s seminal statement: the map is not the territory.

This thought is far less radical than it once was, but it still has much to teach us about writing first-rate fiction. For stories to hold the reader’s imagination, the boundary between map and territory doesn’t just need to be blurred from time to time, but map and territory must merge. Old Man Evil charts the different territories author Vincent Czyz has rambled through over a number of years. On first reading, his eclecticism can be somewhat challenging. We are asked to enter a number of worlds and time frames; still, the moral pressure that Czyz exerts unites these tales, which generally contain gripping conflicts and satisfying resolutions.

“Hamlet’s Ghost Sighted in Frontenac, KS” is probably the earliest story here because it is connected to his first book, 1998’s Adrift in a Vanishing City. I read that collection years ago. Reading this piece, I was impressed once again with Czyz’s inventive use of language, in this case to convey a stupor generated by alcohol and cocaine. Logan Blackfeather, a half-Hopi character, appears in this tale; in another incarnation, he will become the protagonist of Czyz’s recently published novel, Sun Eye Moon Eye. (Sensitivity to the lives of people with mixed Native American blood runs throughout Czyz’s fiction.)

Old Man Evil, particularly the tale “Circle Ceremonies,” features discussions about Native Americans and their way of life: it is seen as a better path, free from the Christian tradition of sin. The story moves the collection into more plot-driven territory, where it stays, often with a focus on characters who leave Czyz’s home state, New Jersey, for Kansas, New Mexico, and Colorado. In “Circle Ceremonies” Sheila, finally liberated from her former lover Rance, discovers an authentic pleasure as she explores the Rockies. In turn, Rance frees himself from the muck of his hometown and heads up to the Catskills.

New Jersey is treated with either ambivalence or repulsion. “Pub Blues” starts out this way: “Passaic was ugly, uglier in the rain.” In the volume’s title story, “Old Man Evil,” the protagonist suffers from a mental breakdown that leads to amnesia. He ends up in a marginalized community in New Mexico. There he begins to recall his past life; when his mind returns to New Jersey it makes a satisfying revelation. The other two New Jersey / New York stories, “Straightsville” and “The Prize,” are less interesting because they do not bring out Czyz’s considerable gifts.

Author Vincent Czyz. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Other yarns in this collection are grounded in the international sphere, no doubt drawing on Czyz’s experiences living and traveling abroad. They span a remarkable series of countries: Serbia, Türkiye, Russia, Poland, and Germany (via Auschwitz). “Chela Kula” confronts us with a tower of skulls, a Serbian monument to martyrdom in the name of the country’s fight for independence. It was constructed by the Ottoman Empire following the Battle of Čegar of May 1809, during the First Serbian Uprising. We see the edifice through the eyes of a tourist couple from the US, Michelle and Michael. Czyz juxtaposes a flashback to the original battle with the somewhat clueless responses of the couple. American innocents abroad (Michelle proudly locates the handsome skull of a voyvoda in the pile). A sequence narrated by the ghost of a warrior adds supernatural flavor to this moving meditation on mortality.

“Arif’s Refusal to Bargain” is one of the most polished and rewarding pieces in Old Man Evil. I was surprised at how much I enjoyed “Tolstoy’s Kunak” because, at first glance, it seemed to be alien territory for Czyz, what with Tolstoy among its characters. But when you consider that the story is set in the Caucasian Mountains, where so many were killed or forced to emigrate to Türkiye during the 19th century, it comes off as another variation on the writer’s habitual concern with probing catastrophes. “Mengele’s Gypsy” draws on Czyz’s Polish background: the town his father’s family came from is a mere 20 kilometers from Auschwitz. One of my college professors — not Bateson — insisted that a writer loses 15% of a narrative’s forward movement every time a flashback in introduced. Czyz proves that this rule was made to be broken — most of his stories deftly dance from the past to the present and back. “Mengele’s Gypsy” is a particularly adept application of this technique.

Old Man Evil continually testifies to the precision and craft of Czyz’s writing, the gripping power of his vision. His imagination covers extensive geographic and historical territory, creating maps whose borders are drawn with the vigor of a nuanced moral temperament.

Jeffrey Kahrs recently published a book of poems called The Far Shore in a bilingual edition of Turkish and English. He’s also published a chapbook from Gold Wake Press and won the Nazim Hikmet Poetry Prize in 2012. His poems, fiction, and nonfiction have appeared in numerous journals. Working with translation partner Mete Özel, their renderings of Turkish poetry into English were nominated for a Pushcart Prize in translation in 2025. Mr. Kahrs lived in Istanbul for 18 years.