Film Review: Love, Distance, and What Remains — “Father Mother Sister Brother”

By Tim Jackson

The recurring rituals, images, and gestures in Father Mother Sister Brother offer moments of dry humor, but suggest that we all belong to one big flawed human family.

Father Mother Sister Brother, directed by Jim Jarmusch. Now screening at the Capitol in Arlington and Coolidge Corner.

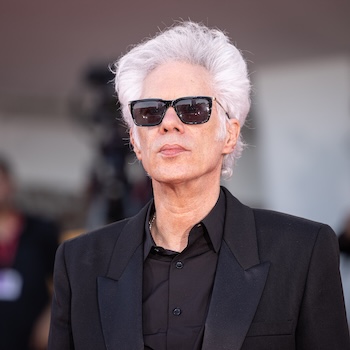

Director Jim Jarmusch at the 2025 Venice Film Festival. Photo: WikiMedia

It feels right that photographs of Jim Jarmusch often show him peering out from beneath dark sunglasses. With his shock of white hair and lean, stern face, he projects a classic cool. I’m reminded of Marshall McLuhan’s notion of “cool,” which he defined in a 1969 Playboy interview as a mode of communication that “allows the viewer to fill in the gaps with his own personal identification.” Coolness, in this sense, invites participation rather than explanation. That “cool aura of disinterest and objectivity,” as McLuhan put it, has long defined Jarmusch’s cinema. His films resist cliché and conventional dramatic turns, favoring understatement and careful observation.

In Father Mother Sister Brother the director draws on this approach in a film that unfolds in three distinct stories and locations, though the narrative could be seen as a unified profile of the modern family. There’s no conventional plot: dramatic momentum is provided through overheard remarks, carefully choreographed, often static visual compositions and angles, small social rituals, revelatory details glimpsed in objects, clothing, gestures, glances, and the director’s telling choice of actors. In this context, sustained conversations — or the silence of non-conversations — come off as voyeuristic. We are invited to judge these characters by measuring them against our own experience while, at the same time, we are asked to piece together their relationships and backstories.

The first episode, “Father,” is set in rural New Jersey. A taciturn father — played by Tom Waits, and credited simply as “Father” — lives alone in a handsome cabin by a lake. He is visited by his grown children, Jeff and Emily: a brother and sister portrayed by Adam Driver and Mayim Bialik. Like their father, neither is blessed with the gift of gab. The scene opens with Jeff and Emily driving along a rural, snow-covered road. Their conversation is sparse, functional. They seem to know remarkably little about their father — there is no mention of a mother. They quietly speculate about how he manages to survive on his own. “Maybe he lives on his Social Security,” Jeff suggests, before adding, almost as an afterthought, “I help him out sometimes.”

When the pair arrives, the greetings are stiff and ceremonial — “Good to see you,” “I love you” — phrases recited more out of habit than feeling. The emotional distance is palpable. The long, awkward silences would put the infamous pauses of Harold Pinter to shame. At one point, Emily notices her father’s Rolex. “It’s not real,” he says flatly. As they leave, Jeff secretly presses some money into his father’s hand so his sister won’t notice. Walking back to the car, he notices a battered pickup truck parked beside the cabin and asks, “Does that thing work?”

“Good enough,” Father replies.

On the drive home, Emily turns to her brother and says, “You know that Rolex was real.”

Back at the house, Father places a phone call, arranging to meet a friend for dinner. “I’ve come into some unexpected money,” he says evenly. “My treat.” With the children gone, he steps outside, pulls the tarp from a gleaming BMW and drives off.

Tom Waits in a scene from Jim Jarmusch’s Father Mother Sister Brother. Photo: NYFF

A similarly nebulous air hovers over the visit of two sisters, Emily and Timothea, played by Vicky Krieps and Cate Blanchett, who are visiting their mother in Dublin. She is portrayed by Charlotte Rampling and credited simply as “Mother.” Emily, her hair dyed pink, arrives in a car driven by her leather-clad friend Jeanette, played by Irish actress Sarah Greene. “Pretend you’re my chauffeur” Emily entreats. Are we to assume she’s covering up a relationship — or putting on false airs? Emily’s manner is casual, her conversation idiosyncratic, her appearance leaning toward the bohemian. Timothea, by contrast, is brisk and officious, her demeanor closer to that of their mother, whose reserve she seems to have absorbed. When Emily begins sorting through a box of books written by their mother, Timothea cautions her, “She doesn’t like to discuss her books.”

This detail hints that the mother’s wealth and formal bearing may be bound up with her success as a writer. She is as fastidious as the décor of her well-appointed townhouse. Her welcome includes an immaculate presentation of afternoon tea. Rampling, with her sly face and hooded eyes, is a figure of repression; she is all manners and propriety, a study in cultivated reserve. Both daughters remain guarded during their lunchtime chatter. A Rolex watch makes another appearance in the film — what does it symbolize? Is it about economics, status, or material values? Formal overhead shots of the tea being poured echo how coffee is served in the first episode. Each group raises a toast. “Can you toast with tea?” becomes a comic refrain, recalling the earlier, “Can you toast with coffee?”

Like the meal itself, the toast feels perfunctory, part of a ritual that shapes the limits of conversations filled with emotional distance and careful restraint.

Vicky Krieps, Cate Blanchett, and Charlotte Rampling in a scene from Jim Jarmusch’s Father Mother Sister Brother. Photo: NYFF

The final episode opens in Paris. Twin sister and brother Skye and Billy, played by Indya Moore and Luka Sabbat, drive through the city’s streets. As their conversation unfolds, it emerges that their parents were killed in a plane crash in the Azores. They are on their way to the apartment Billy has already emptied.

“Aren’t you glad we were raised by bohemians?” Billy asks. “Yes, I guess I am,” Skye replies.

Inside the stripped-down apartment, memories surface. The now-empty space floods with memories of childhood that seem, in retrospect, serene. Looking through old photographs of their childhood, Skye is overcome with emotion, tears welling as the past presses in. Jarmusch has said in interviews that he initially wanted no crying in these scenes, but when Moore asked if she could let the moment play out naturally, the result was so spontaneous and right that it moved the director himself to tears.

Unlike the earlier episodes, the siblings here display a genuine warmth with each other, a sense of shared history and mutual understanding even though their relationship to their parents, and to the past itself, remains unresolved. Moore and Sabbat share an easy, affecting chemistry that’s markedly different from the strained familial dynamics of the earlier episodes.

A landlady appears, played by 80-year-old French legend Françoise Lebrun in a small but emblematic role. The parents, it turns out, still owed three months’ rent, but she has let it slide. She also allowed Billy to clear out the apartment without any dispute. It is a brief but telling detail, about the parents, certainly, and perhaps about a particular strain of French humanity. One can’t help but wonder — would an American landlord be so forgiving?

Luka Sabbat and Indya Moore in a scene from Jim Jarmusch’s Father Mother Sister Brother. Photo: NYFF

Much is left unexplained. Skye and Billy are unsure about the nature of their parents’ bohemian life. From the photographs, we glimpse that this was a biracial family. The absence of their parents, who appear to have remained together until their sudden, untimely death, means that this segment has a more grounded, quietly bittersweet register than the others. Loss lingers, but connection endures. In the last shot, the siblings stand before a storage unit containing all their parents’ furniture and belongings. “What are we gonna do with that?” Skye asks. “I don’t know,” her brother replies.

They walk off.

It is a quietly devastating moment, one that poses a gentle existential question for anyone with adult children: what is the value and meaning of the detritus of our lives once we are gone?

The recurring rituals, images, and gestures in Father Mother Sister Brother offer moments of dry humor, but suggest that we all belong to one big flawed human family. Skateboarders are observed in the opening of each section: observed by each group, they glide through as a recurring visual motif — simultaneously a symbol of youth and a signifier of motion and freedom, of lives unburdened by the accumulated weight of the past.

Can anyone ever fully know the lives their parents once led? What do we do with the emotional and material remnants of the past? Are family ties merely perfunctory obligations, or do they invite honesty and nurturing across the generations? Jarmusch poses these questions obliquely — intimating rather than declaring, asking attentive viewers to measure these pared-down, archetypal stories against the contradictions and quiet consolations of their own lives.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter-skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story. And two short films: Joan Walsh Anglund: Life in Story and Poem and The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: "Father Mother Sister Brother", Cate Blanchett, Charlotte Rampling, Indya Moore, Jim Jarmusch, Luke Sabbat