Book Review: Dissecting the Past — Andy McPhee’s Chilling History of America’s Medical Progress

By Sarah Osman

For all its rewards as a gross-out experience, The Doctors’ Riot of 1788 has an ethical question at its core: does the search for medical knowledge outweigh our respect for human life and death?

The Doctors’ Riot of 1788: Body Snatching, Bloodletting, and Anatomy in America by Andy McPhee. Prometheus, 248 pages, $29.95

I have a deep, inexplicable love of gross medical history, partly because it is so reassuring. Learning about how horrific medicine was before makes me grateful for medicine today. It also makes me wonder what medical practices will look like 100 years from now. So, while reading about surgery without anesthesia is inevitably repulsive, I can’t stop doing it.

I have a deep, inexplicable love of gross medical history, partly because it is so reassuring. Learning about how horrific medicine was before makes me grateful for medicine today. It also makes me wonder what medical practices will look like 100 years from now. So, while reading about surgery without anesthesia is inevitably repulsive, I can’t stop doing it.

Thus it was mandatory to pick up Andy McPhee’s new book, The Doctors’ Riot of 1788. This account of doctoring takes place during the 18th century, at a time when medical lecturers were given license to demonstrate human anatomy by dissecting cadavers in front of their classes. After the Revolutionary War, the pedagogues realized that they needed way more bodies than they had to put their lessons across. So the macabre practice of body snatching was born. Referred to as “resurrectionists,” these men snuck into cemeteries at night, dug up a body or two, and sold them to an anatomist.

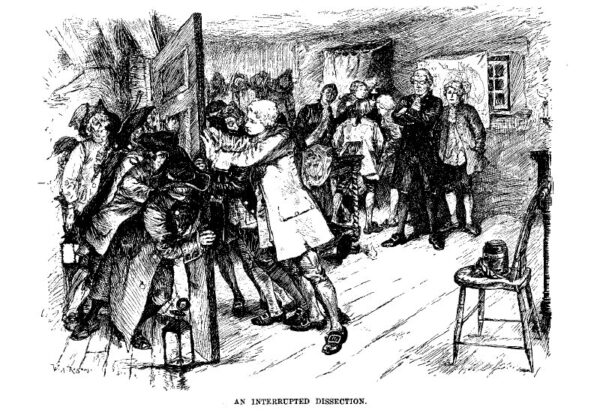

One night in April, 1788 in New York City, word got out that a body was being snatched. Locals had had it with the impious pilfering. They descended on an anatomy lab — several days of bloody rioting followed.

The title of the book is The Doctors’ Riot of 1788, but McPhee covers much more than that event. He also explores what life was like — particularly regarding the progress of medical knowledge and contemporary health standards — in post-Revolutionary War America. This section doesn’t deal directly with medical mayhem, but it sets the scene for what led to the riot in the first place. McPhee focuses on major civic players and medical forefathers, many of whom you’ll recognize. In terms of the state of doctoring, McPhee explores the history of dissection. Interestingly, dissection wasn’t considered taboo in the 1500s. Spectators turned up to marvel at a glimpse of the innards of the human body; religious authorities saw it as a remarkable way to study God’s handiwork. Of course, those who were dissected were considered the refuse of society — most of those sliced-and-diced had been former prisoners. McPhee’s writing in this section is particularly vibrant — it is a fascinating look at what went on in early medical studies of anatomy.

McPhee dives into the history of medical education in America up until 1788 before focusing on medical practices during the late 18th-century, a toolkit that included bloodletting, purging, and blistering. If the word “leeches,” sends shivers down your spine, then from here on the book will be rough going. But, if you want to learn how amputations were performed during the Revolutionary War, this is an indispensable read.

“An interrupted dissection,” by William Allen Rogers, Harper’s Magazine, October 1882, vol. 65. Photo: WikiMedia

McPhee finally arrives at detailing the job of body snatcher. Stealing a corpse was no easy feat — for some medical students, it was a requirement for the class. The author dramatizes the task in all its dimensions, including the sensory. For example, McPhee describes the different odors certain parts of a cadaver give off. The text is disturbing, atrocious, and amazing; a portrait of decomposition that is both compelling and disgusting. (I couldn’t stop reading these passages, despite thinking .. ewww.) In the hands of a less capable writer, this section would be gross in the extreme. But McPhee deftly balances the medical facts with the backstories of the doctors and students for whom this practice was a necessity. McPhee eventually delves into historic burial practices, and how race played a predictable factor in which bodies were stolen.

For all its rewards as a gross-out experience, The Doctors’ Riot of 1788 has an ethical question at its core: does the search for medical knowledge outweigh our respect for human life and death? Doctors and medical students at the time needed cadavers to study anatomy but, by making off with bodies, they disrupted social norms and trampled on family bonds. McPhee raises important questions about other medical “practices” that claim to further the progress of medicine but pose alarming moral conundrums. Are there any limits in the search for scientific truth, particularly discoveries that promise profit? The quandaries of the late 18th century still plague us. One need only look at how AI is upending the field of medicine. Will people 100 years from now see AI as an instrument of transformation? Or of disruption? Will there be riots, virtual or otherwise?

Sarah Mina Osman is based in Los Angeles. In addition to The Arts Fuse, her writing can be found in The Huffington Post, Success Magazine, Matador Network, HelloGiggles, Business Insider, and WatchMojo. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of North Carolina Wilmington and is working on her first novel. She has a deep appreciation for sloths and tacos. You can keep up with her on Instagram @SarahMinaOsman and at Bluesky @sarahminaosman.bsky.social.