Book Review: Trapped in the Present Tense — The Bleak Masculinity of David Szalay’s “Flesh”

By Ed Meek

David Szalay’s novel focuses on a current type of western male: one whose emotional growth and adult development are stunted or limited by his inability to express himself and understand who he is.

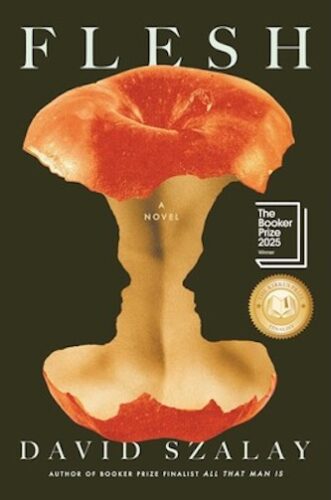

Flesh by David Szalay. Scribner, New York, 353 p.p., $28.99.

Flesh won the Booker Prize in 2025 and has generated David Szalay, the author of Turbulence, London and the Southeast, and All That Man Is, an enormous amount of buzz. (He has also snagged the Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize for Fiction.) The novel is written from the point of view of István, a white male, and covers his life from the time he is fifteen until he is in his sixties. Although he was born in Hungary, István spends much of his adult life in London. He is posited by Szalay to be representative of a current type of western male: one whose emotional growth and adult development are stunted or limited by his inability to express himself and understand who he is.

Flesh won the Booker Prize in 2025 and has generated David Szalay, the author of Turbulence, London and the Southeast, and All That Man Is, an enormous amount of buzz. (He has also snagged the Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize for Fiction.) The novel is written from the point of view of István, a white male, and covers his life from the time he is fifteen until he is in his sixties. Although he was born in Hungary, István spends much of his adult life in London. He is posited by Szalay to be representative of a current type of western male: one whose emotional growth and adult development are stunted or limited by his inability to express himself and understand who he is.

The novel is constructed to reinforce this static perspective. The entire narrative is told in the present tense and its sparse dialogue is filled with words like “okay” and “things,” substitutes for revealing details. The action often happens off-stage; the reader only receives explanations when István tells us rather than shows us what happened. In other words, the author has intentionally undermined — even overturned — a number of rules of conventional fiction. And Szalay’s unusual approach effectively dramatizes his vision of undeveloped masculinity. This is a protagonist who perpetually lives in the present tense. He has no sense of the future or agency in the present. He merely reacts to events. In another flouting of novelistic convention, István doesn’t want anything. This makes for an interesting experiment in storytelling — if you are a writer. For example, Zadie Smith asks when she picks up a novel, “how has this person made the novel new? And for me, this novel was new…Extraordinary.”

A key text for understanding how men are viewed in contemporary fiction is Herman Melville’s Billy Budd. The innocent but limited Budd stutters so when he is unjustly accused of mutiny his frustrated response to the accusation is a mortal act of violence. And he pays for that aggression with his life. István also responds to challenging situations at crucial moments in his life with force, and he pays a serious price each time. The one time he rescues someone else from possible harm, he is rewarded. There are suggestions of a fable about repression here, as in Billy Budd.

Unfortunately, the mechanical simplicity of Flesh‘s narrative, its determined paucity of internality, becomes annoying. Here is István thinking about his deployment in Iraq:

He realizes that the things that are so important to him—the things that happened, and that he saw there, the things that left him feeling that nothing would ever be the same again—they just aren’t important here.”

Szalay’s István leaves it at that. This is terrible writing.

At another point, István gets a job driving for a rich woman. She asks him about himself. The results are predictable.

“Karl says you were in the army,” Mrs. Nyman says.

“Yes.”

“How was that?” she asks.

“How was that?” The traffic was moving again and he has to focus on it for a moment.

“Yes,” she says.

“It was…” He wonders what to say, what sort of answer she’s looking for. “It was okay,” he says.

“It was okay?”

“Yes.”

“What does that mean?”

“What does that mean?”

“Yes.”

“It was okay.”

The word okay is used hundreds of times. It is kind of like a conversation between a parent and a teenager about school that goes on and on. István has difficulty expressing himself, like the protagonist of the film Train Dreams. You know why the talk is so anemic and non-stop, but that doesn’t make the dialogue compelling. The writing makes a fair amount of Flesh boring. That said, it also makes for a quick read.

One of the intriguing aspects of Flesh is how it treats violence. István periodically finds himself resorting to physical force. When he does, he feels detached from what he does, never in control. At one point, he punches a hole in a door — for no reason. As someone who grew up in a working-class city, I can identify with that compulsion to strike out. There were daily fights in my grammar school. In that sense, Szalay has his finger on a problem that many men have with controlling their urge to lash out. For some males, it is an urge that they can’t contain. And that pertains to the actions of societies as well: The United States has a long history of using violence to resolve its problems, most recently on display with the actions of ICE. Szalay’s tale of an emotionally stunted man — trapped in a never-ending present, with no sense of the past or future — sheds an illuminating light on that masculine syndrome.

Ed Meek is the author of High Tide (poems) and Luck (short stories).