Book Review: Choreographer George Balanchine — Cavalier or Creep?

By Debra Cash

Balanchine Finds His America is written primarily in the present tense, so that reading the book is like watching a never-to-be-repeated dance performance.

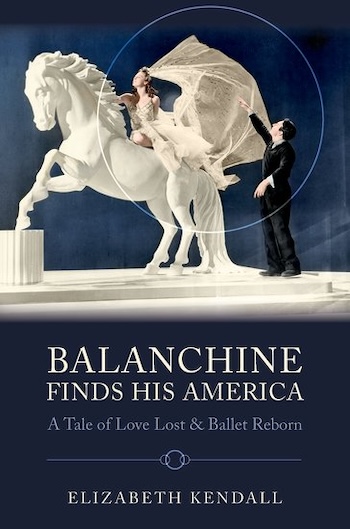

Balanchine Finds His America: A Tale of Love Lost and Ballet Reborn by Elizabeth Kendall, Oxford University Press, 2025, 232 pp, $29.99

Do we really need another book about George Balanchine?

Shakespeare has been dead 409 years, and scholars (not to mention filmmakers!) are still interrogating and remixing his oeuvre. Given that the great Russian-American choreographer left the world as recently as 1983, we can expect at least a bookshelf (or equivalent digital storage device) worth of Balanchinalia to appear in the current century.

The real question is: do we really need another book about George Balanchine by Elizabeth Kendall?

Kendall’s 2013 Balanchine & the Lost Muse: Revolution & the Making of a Choreographer is about the side-by-side training in imperial St. Petersburg of Balanchine and Lidia Ivanova, piecing together the world fractured and remade by the Russian revolution. The volume is one of the valuable, if esoteric, footnotes to the Balanchine bookshelf. Her new volume, Balanchine Finds His America is something of a sequel.

While Kendall is comfortable with Russian-language sources, this one brings her to New York, and Hollywood, and the hardscrabble creation of an American-inflected high balletic art. It also means that she is wading into more contested territory, where other writers and the surviving coterie around “Mister B.” and his acolytes have more stake regarding her suppositions and evaluations.

In the book’s preface, Kendall opens up her own backstory. She wasn’t initially a ballet lover — she sided with the ’70s iconoclastic, rebellious avant-gardists in New York’s dance scene — but found herself unaccountably moved by a performance by the great Violette Verdy in Balanchine’s Raymonda Variations, a “Watteau ballerina” who conveyed not only exceptional beauty but a sense of her authority “presiding over the action onstage” and the personal agency of her interpretive choices.

Soon though, Kendall learned what was common knowledge. Balanchine had groomed — certainly as artists and perhaps subliminally, as potential romantic partners — bedded, and occasionally married, and then tossed away (or was ultimately rejected by) the ballerinas who were collectively dubbed his “muses.” The late New Yorker critic Joan Acocella made the case that being a “muse” was a rarefied term for being a co-creator, an almost-equal collaborator, something I am not sure I accept.

There is no question that Balanchine tuned his art to each favored ballerina’s gifts (and for that matter, the talents of some of his male dancers as well). Ballet choreographers have always done that: Lev Ivanov showcased 32 turning-in-place fouettes in the climatic moments of Swan Lake’s “black Swan” pas de deux because the virtuoso Italian ballerina Pierina Legnani could perform them.

The difference is that Balanchine’s choreographic choices were as often as not built on his personal attractions: as former Balanchine dancer turned historian and cultural critic Jennifer Homans notes in Apollo’s Angels “The relationships Balanchine had with his dancers were never peripheral. They were part of the choreography.” The melancholy male lover yearning for an unattainable or lost female love object became the master’s central theme.

Kendall’s question about whether Balanchine’s behavior would have been called out more forcefully in the contemporary post–Me Too environment is necessarily hypothetical. There is a general agreement among people who were there at the time that Balanchine’s New York City Ballet (and the nascent companies that preceded it) had no casting couch: the dancers who said no still had great parts created for them. While Balanchine favored creating ballets featuring the women he was sweet on, by all accounts he was a man who was serially in love and inspired by his feelings, not a Harvey Weinstein-style predator.

Yet public awareness of his patterns leads to two practical questions. What, if anything, should protect young dancers — whose art work is made of their young bodies — from inappropriate sexual approaches by older and more powerful men or, for that matter, women? And how does this knowledge of the personal context in which great works were created change, if at all, our appreciation and understanding of them?

Kendall doesn’t mention it, but her book is part of an ongoing debate in which Homans and others have labeled classical ballet, and in particular Balanchine’s repertory, “ethical.” Here’s Homans:

[Balanchine] taught [his dancers] to respect ballet as a set of ethical principles — and hard work, humility, precision, limits and self-presentation. They knew they were becoming aristocrats of a sort, even when they were also street kids or corn-fed Midwestern gals. Their direct, open, and unselfconscious physical trust and daring — their willingness to submit to the laws of ballet and music even when they also broke them — fit perfectly with Balanchine’s aesthetic.

That verb, submit, makes me queasy.

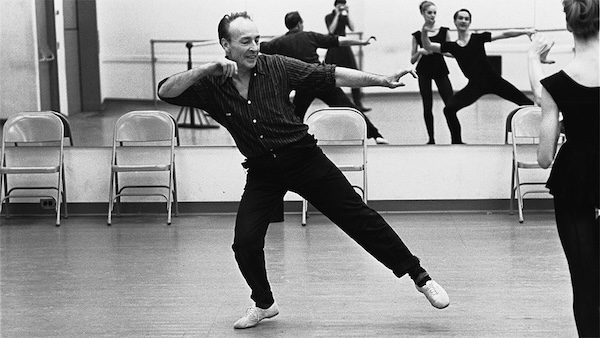

George Balanchine in rehearsal. Photo by Martha Swope. Photo: The George Balanchine Trust

In the last pages of that book, Homans added, “ballet has always been an art of order, hierarchy, and tradition. But rigor and discipline are the basis for all truly radical art, and the rules, limits, and rituals of ballet have been the point of departure for its most liberating and iconoclastic achievements.”

Kendall is interested in the roots of that liberation. She opens her book with Balanchine’s first day in America in 1933, imagining him peering down from his hotel window at Central Park. She glancingly refers to the 29-year-old’s prior achievements, particularly with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, but isn’t emphatic enough that if he had only created Apollo, to a score by his lifelong collaborator, Igor Stravinsky in 1928, he would already have shaped ballet’s direction towards modernity.

Balanchine Finds His America is written primarily in the present tense, so that reading the book is like watching a never-to-be-repeated dance performance. Kendall can turn a cogent phrase: the corps of women in Serenade, the first ballet Balanchine made for American dancers, is described as “new-world speed blended with old-world manners. They’re Giselle’s flock of Wilis, woken up.” Kendall is generous citing her sources (you never have to wonder where she came up with a piquant detail) and honest about her informed reconstructions of conversations that no one had documented. The tone is friendly: we may be entering rarefied cultural enclaves, but she is bringing the reader along for the ride. Psychoanalyzing Balanchine — suggesting his sex drive was in part an overcompensation for a desperately deprived childhood in post-Revolutionary Russia — however, should be above her pay grade.

Nonetheless, Kendall does justice to both Balanchine’s gifts and the women who entered his orbit, and more than occasionally his bed. Each of the ballerinas (they were all ballerinas) — from the 16-year old Heidi Vosseler (who later married the ballet-inspired tap dancer Paul Draper!), Holly Howard, and an unnamed “Radio City Music Hall chlorine”) — are described less as notches on his belt than inspirations for creative directions. It’s his affair, marriage, and finally rejection by Vera Zorina that brings the text together, not least because Kendall has ample documentation of their relationship and there are records of the work it engendered.

Zorina, nee Eva Brigitta Hartwig, began her career as a 12-year-old in Max Reinhardt’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (the Russified name was chosen because it was one of the few on a proffered list that she could pronounce). Balanchine’s love with her was bone-deep; as her star ascended in Hollywood and work separated them, his mournful, misspelled letters (“I am so lonsom”) tell of a real connection. And we have some of the work he made for her talents, the jazzy, glam-noir Slaughter on Tenth Avenue for 1939’s On Your Toes.

For a brief time, they’re a Hollywood and New York power couple. Late in their on-again-off-again relationship, in 1942, she will get to ride an elephant in Balanchine and Stravinsky’s Circus Polka for Barnum, Bailey and Ringling. (Kendall, delightfully, is able to tell us that the sawdust, laid in concentric circles, is pink and white. That’s the kind of researcher she is.)

Oddly enough, Kendall deducts, Zorina seemed to be one the few women who wasn’t particularly attracted to Balanchine sexually. He gets over it eventually, and becomes pragmatic. By the time he marries Maria Tallchief in 1946 (finding, Kendall says, she is “a devout Catholic where sex is concerned”), he tells her, “We can get married and work together, and if it lasts only for a few years, that’s fine. If it doesn’t work, well, that’s fine too.” A helluva proposal. It won’t last, of course. But from that union, audiences will get Firebird.

Unlike some other writers, Kendall is good on the roots of Balanchine’s institutionalization. She unravels the money woes, the deal-making, the relative satisfactions of Hollywood. Contrary to his own self-aggrandizement, it wasn’t only Boston philanthropist Lincoln Kirstein who created the conditions for creating a home-grown American ballet, but the dueling rivalries of various offshoots of the Ballets Russes (featuring a number of Balanchine’s frenemies and rivals), the up-and-comer studios of American dance teachers like the Littlefield sisters, Catherine and Dorothie, of Philadelphia, whose students would seed his ensemble’s farm team, and even showbiz images of skating star Sonja Henie.

If, by the end of Balanchine Finds His America, Kendall has been diverted from her investigation of how “Angel and Eros — divine spirit and sex — [were] completely intertwined,” those would surface again, later, in his explosive pursuit of young Suzanne Farrell in the ’60s. Perhaps, if books like this had been written by the time she left Ohio for New York, Farrell would have been forearmed.

Debra Cash is a founding Contributing Writer to the Arts Fuse and a member of its Board.

Tagged: "Balanchine Finds His America", "Balanchine Finds His America: A Tale of Love Lost and Ballet Reborn", Elizabeth Kendall

Such a nice piece of writing, Debra! So much fun to read.

thanks!

A really super interesting, thought provoking, beautifully written book review! Thank you very much. We all need stuff like this to keep our ballet/ dance love hungry enough for more ♥️

Thanks for including the clip of Bettijane Sills. (Being mostly dance-ignorant, I had never heard of her.) Even with her equivocations, it gives me a better picture of Balanchine’s company — and his relationships with women — than I think this book would. But I guess this was all pre-Farrell? Anyway, thanks for the excellent piece!

… and the clip from “On Your Toes”! …. with Eddie Albert tap dancing…. and the bartender from “Casablanca”!