Visual Arts Review: Threads of Tradition — The Quiet Brilliance of “One Hundred Stitches, One Hundred Villages”

By Lauren Kaufmann

Although the work seems timeless, its modernity reflects a culture that reveres its age-old traditions and preserves them over many generations.

One Hundred Stitches, One Hundred Villages: The Beauty of Patchwork from Rural China, at the Boston MFA through May 3

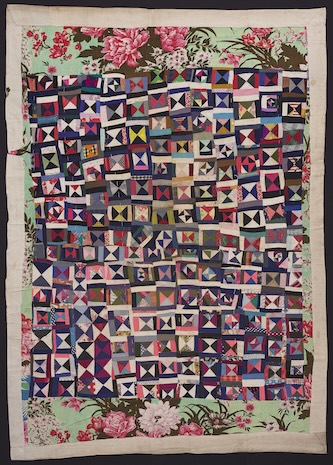

Sofa Cover, 2019. Zheng Yunyang (Chinese). Joel Alvord and Lisa Schmid Alvord Fund. Reproduced with permission. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

One Hundred Stitches, One Hundred Villages is a hidden gem. Tucked away in a small gallery in the Art of the Americas wing, this exhibition is a joyful ode to color, pattern, and creative ingenuity. Comprised of about 20 handmade patchworks by contemporary Chinese women, the show speaks to a simpler time and place. On the one hand, the work seems timeless; but it also reflects the modernity of a culture that reveres its age-old traditions and preserves them over many generations.

The term—one hundred villages—appears in literature and folklore to describe disparate communities that work together to preserve ancient traditions by collaborating and sharing resources. Thus, the exhibition title refers to the concept of a collective identity or shared heritage among rural populations.

Kang Cover, 1960s. Ms. Qin (Chinese). Joel Alvord and Lisa Schmid Alvord Fund. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

There’s a long tradition in China—dating from ancient Buddhist times—of using rags for clothing, curtains, and bed covers. For thousands of years, Buddhist monks have dressed in patchwork robes, and this practice has spread to everyday people. As a means of expressing humility and shunning materialism, Chinese women use everyday rags to create richly designed compositions. They don’t sell their patchworks, so the women are free to experiment with novel combinations and use whatever fabrics come their way.

The pieces on display are utilitarian—bedcovers, door curtains, sofa covers, and children’s clothing—but the selection and arrangement of fabrics reveal an innate sense of design. Although the makers are not trained artists, they piece together swatches of fabric as if they were seasoned quiltmakers, displaying a keen sense of color and composition. The women use whatever cloth is available, yet they come up with striking, and sometimes, intricate patterns. Some of the patchworks feel contemporary, while others strike a more traditional look, akin to conventional quilt patterns. Some are meticulously stitched and perfectly symmetrical: others appear more randomly assembled. While some of the women sewed their patchworks by hand, others used sewing machines.

Kang Cover (1960s) is a hand-stitched beauty by Mother Qin. Made up of many small squares, each comprised of four triangles, this patchwork is used as a cover for a kang, a large wooden sleeping platform common in Northern Chinese homes. The small squares are not perfectly aligned, but their off-kilter arrangement, combined with the repetition of colors and shapes, creates a pleasingly improvisatory rhythm. Mother Qin picked a peony-filled fabric for the border; peonies appear often in Chinese art and literature, and symbolize wealth, honor, and prosperity.

The colors and composition of Door Cover (1980s) evoke modern paintings from the ’60s and ‘70s. This work is composed of equally sized right triangles made of bright corduroy fabric. The triangles are neatly stitched together on a sewing machine. Although the maker repeated fabrics, she varied the color combinations throughout the piece. In some cases, triangles are made up of several small strips of fabric. The entire composition is bordered with a wide black fabric, which serves as a perfect frame for the colorful composition.

Door Cover, circa 1980s. Unidentified artist, Chinese. Joel Alvord and Lisa Schmid Alvord Fund. Photo: the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Bed Cover (1970s) is a dazzling display of 9,000 hand-stitched scraps of fabric. The unknown maker sewed together 690 squares, each made up of triangles, with a small square in the center. This remarkable work was discovered in a flea market stall run by a used-fabric vendor. The pattern remains consistent throughout, but the fabrics and colors are mixed in a way that produces a lively effect.

In Sofa Cover (2019), Zheng Yunyang used scraps from a local tailor to create an eye-popping composition. Made up of a series of octagons, with stars in the middle, this patchwork has a decidedly modern feeling. Employing just three colors—red, white, and blue—Yunyang varied the arrangement of the fabrics in a way that makes each square different from the others. The label explains how, in 1975, the maker and her husband borrowed money from friends, family, and neighbors to purchase a sewing machine. To pay them back, Yunyang made them clothing. She is now regarded as the best patchwork maker in her village.

Exhibition curator Nancy Berliner journeyed to northern China to select the work and meet with the artists. Photographer Lois Conner accompanied Berliner and brought back photos and some wonderful videos showing the women at work. There’s a lovely photo of Zheng Yunyang holding up one of her patchworks. The videos of the women at their sewing machines and cutting fabric provide you with vivid images of them at work. There is footage of them occupied at daily tasks; you can imagine them sewing in between their everyday chores and caring for their families.

The exhibition is an impressive display of everyday craft, serving as a window onto another culture—its lifestyle and enduring philosophy. In recent years, the MFA has mounted several shows that highlight the work of artists and craftspeople whose creations are not typically shown in major museums. To discover that women in rural Chinese villages are still making these beautiful, useful pieces gives one hope. Prioritizing simplicity and downplaying materialism are worthy goals. As you marvel at these eye-catching compositions, you can’t help but think about other parts of the world, where long-held craft traditions are still honored and respected. Our world-view is enriched by exhibitions like this one.

Given my sense of the value of One Hundred Stitches, One Hundred Villages, I found its location puzzling. As I meandered my way to the show, I wondered why an exhibit of work by contemporary Chinese women is mounted in the lower level of the Art of the Americas wing. I understand that the size and scope of the exhibit don’t necessarily call for a significant amount of space, but it did strike me as odd that it was placed where it was. The exhibit is well worth the search, offering a glimpse into a long-held tradition honoring simplicity, beauty, and human ingenuity.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions.

Tagged: "One Hundred Stitches One Hundred Villages", Chinese art, MFA Boston