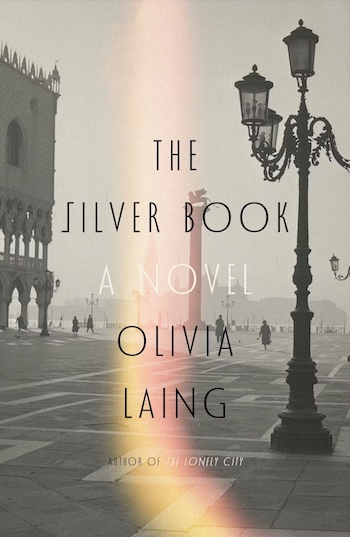

Book Review: Art, Desire, and Danger in Olivia Laing’s “The Silver Book”

By Peter Walsh

Olivia Laing’s hard-driven narrative, set mostly in 1975, combines a gay romance with a literary text about the dangers of resurfacing fascism, a discourse on 20th-century avant-garde film-making, and a political thriller.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 256 pages, $27

When E.L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime appeared in 1975, critics remarked on its “original” and “radical” device of mixing fictional characters with real historical celebrities— people like J. P. Morgan, Booker T. Washington, Henry Ford, Emma Goldman, Sigmund Freud, and Harry Houdini— and its fictional recreation of actual events. The book was adapted as a movie, directed by Milos Forman, and as a wildly successful, Tony Award-winning Broadway musical— one of those true classics of musical theatre that is always playing somewhere.

When E.L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime appeared in 1975, critics remarked on its “original” and “radical” device of mixing fictional characters with real historical celebrities— people like J. P. Morgan, Booker T. Washington, Henry Ford, Emma Goldman, Sigmund Freud, and Harry Houdini— and its fictional recreation of actual events. The book was adapted as a movie, directed by Milos Forman, and as a wildly successful, Tony Award-winning Broadway musical— one of those true classics of musical theatre that is always playing somewhere.

Since then, Doctorow’s innovation, sometimes cited as a precursor to postmodern historical fiction, has been taken up so persistently that has almost become a subgenre of its own. Sir Julian Fellowes’ scripts for the HBO series The Gilded Age, for example, appropriate some of the same famous figures as Ragtime. The 2025 top-ten movie release Hamnet, based on what little is known of William Shakespeare’s family life, is an adaptation of the best-selling novel by Maggie O’Farrell.

The fictionalized celebrities in Olivia Laing’s new novel, The Silver Book, include the great Italian film directors Federico Fellini and Pier Paolo Pasolini, the American actor Donald Sutherland, and the two-time Academy Award-winning Italian costume and production designer Danilo Donati, who plays a major role in the plot. All four of these are safely dead— “The dead cannot be libeled,” my attorney once explained to me. “They have no rights.”

The marketing advantages of including famous names in your work of fiction are fairly obvious. “You have built-in name recognition and interest,” a playwright, who had just cast me in his play about Lizzie Borden, once told me. “You don’t have to explain who these people are because readers already know.” It’s a publicity tactic even Shakespeare was known to exploit to his advantage.

Laing’s hard-driven narrative, set mostly in 1975, combines a gay romance (with Donati at its center), with a literary text about the dangers of resurfacing fascism, a discourse on 20th-century avant-garde film-making, and a political thriller. Not surprisingly, these threads do not cohabit the book entirely peacefully: there is a certain amount of jostling for space and attention. In particular, the complications of the romance tend to expand, particularly at the expense of the political thriller, which, despite its shocking climax (the brutal and still unsolved real life murder of Pasolini) gets mostly squeezed into the book’s final pages.

Laing’s prose style is clean, unaffected, and polished, well within modern realist traditions, written entirely in the present tense, without quotation marks, and mostly in short passages. All of these qualities combine to give her writing the kind of restless momentum that reviewers like to describe as “engaging” or “haunting.” They may also reflect the breakneck speed of Laing’s composition, as described in the accompanying publicity materials.

Pier Paolo Pasolini in 1964. Photo: Wiki Common

In the book’s opening pages, its 22-year-old protagonist, a red-haired English artist and recent Slade School graduate named Nicholas Wade, catches sight of a newspaper headline that induces nausea. Panicked by what he reads (the author does not immediately share it with the reader), Wade abruptly flees his London apartment, tossing the key into the Thames and traveling, on impulse, to Venice, where he has never been. There he is accosted by Donati while sketching at the church of San Vidal. Donati thinks of Vivaldi, the Venetian “red priest” and baroque composer. The reader is not told how it is accomplished, but Nicholas wakes up in Donati’s bed.

Wade and Donati (who call each other “Nico” and “Dani”) become serious lovers, in a relationship that remains passionate throughout its growing complications. Meanwhile, Donati is in the midst of research for the Fellini film, Casanova, then beginning pre-production at Rome’s legendary studio complex, Cinecitta. Conveniently for Nico, who is homeless and penniless, Dani appreciates not only his young body and flaming hair but his drafting talents. He quickly takes Nico to Rome as his assistant on Casanova and soon also on the notorious Pasolini film, Salo, the director’s notorious, anti-fascist last picture. These two, intensely involving projects run through most of the book like freight trains on parallel tracks, with the master and his fresh assistant hopping back and forth between them, like cinematic hoboes. As the spine of the plot, the unfolding of the two films in production is a brilliant choice. They make for a rich backdrop to the love affair.

Despite his central role, Nico is lightly sketched. At first we know almost nothing about him except that he is young, red-haired, very pale-skinned, talented, and irresistibly beautiful. Many pages pass before we learn what spooked him back in London. Laing dribbles out bits of his backstory throughout the first two thirds of the book. It’s a standard technique for keeping up the page-turning, much beloved by the “sensation” novelist Wilkie Collins, who is said to have advised would-be serial novelists “make ‘em laugh, make ‘em cry, make ‘em wait.” Laing handles the device well, without inducing overly much readerly frustration.

Author Olivia Laing. Photo: Johnny Ring

Nico, however, remains a bit smudged. His main function in the plot, as the character holding together its sometimes feuding parts, tends to cramp his fleshing out as a fully developed, though fictional, human being. Although most of the book is narrated through his eyes, Nico remains in the shadow of his celebrity associates, who, after all, have famous and fascinating lives of their own, well off the pages he inhabits.

Dipping into a historical novel is, for me, like wading into an unknown body of water: bare feet anxiously feeling for sharp rocks or mucky bits. There’s always the danger that a glaring anachronism or a serious clash between the factual characters and their fictional counterparts will surface the bloated corpse of the Willing Suspension of Disbelief. Laing, thankfully, avoids these pitfalls with aplomb. She says little about her presumably extensive sources. She thanks Luigi Piccolo, who heads the Roman costume workshop Sartorial Farani and assembled the historic costume collection there, “for talking to me about Donati” (he does the same for a general audience in a current YouTube video, where he shows off some costumes from Canova) and she dedicates the novel jointly to Donati (died in 2001) and to the memory of American artist Robert Indiana, who took a series of photographs on the set of Salo that were subsequently published. The careers of Fellini, Pasolini, and their films that Laing fictionalizes have been massively documented, of course. Yet heavy book research never seems to intrude into Laing’s prose as it too often does in historical fiction, and her evocations, especially of the loosely organized chaos that is the creation of a feature film, are completely convincing in their rich, almost documentary detail.

Laing’s writing style suggests to me the literary tone of the mid-’70s, which formed a bridge between the strict, minimalist realist styles of earlier in the century (think Hemingway and Fitzgerald) and the maximalist, post-modern tastes that were then emerging (think Pynchon and Barthleme). Her book particularly reminds me of John Fowles’ 1974 novella, The Ebony Tower, though the famous elderly artist in that book was as fictional as its young artist protagonist. The Silver Book also seems to fall into a long literary tradition of tales of outsider protagonists drawn into the unexpectedly mesmerizing, ambiguously mysterious and erotic worlds of Italy: Goethe’s Italian Journey, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun, Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, and Daphne du Maurier’s psychological horror story, “Don’t Look Now,” the latter adapted into the 1973 film of the same name starring (who else) Donald Sutherland, who returned to Italy soon after wrapping to play the title role in Casanova.

This book is also, inevitably, about sex: the kind of outsider sex that fascists like to condemn while indulging in it, as they do in Salo, on the down low. Sex pervades all the sub-themes and looms in the lives of its characters, fictional and historical alike, and lies at the core of the two classic films it invokes. The sex starts out obliquely but becomes increasingly graphic, especially in Nico and Dani’s affair. The queer eroticism of the book will undoubtedly be one of its main selling points. Yet Laing treats it matter-of-factly, with no sense that it belongs out of the frame. “What’s gotten into you?” Laing has Dani tell Nico at one point. “Who are you to judge what kind of sex someone has? Don’t do that again.”

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles, and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.