Poetry Review: The Devil’s Sonnets — John Berryman’s “Only Sing”

By Michael Londra

Poet John Berryman’s choice of minstrelsy in his Dream Songs is not just a distraction that can be explained away by aficionados — it is impossible to excuse or forgive.

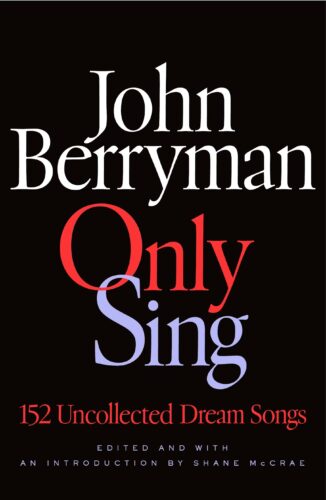

Only Sing: 152 Uncollected Dream Songs by John Berryman. Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 192pp, $28.00

Sigmund Freud posited a mysterious connection between sex, love, and death in his 1920 book Beyond the Pleasure Principle. He saw an obscure subterranean nexus in the human psyche that consciously rejects—yet counterintuitively remains attracted to—the inevitability of mortality, generating positive creative energy from thoughts of our inexorable extinction.

Sigmund Freud posited a mysterious connection between sex, love, and death in his 1920 book Beyond the Pleasure Principle. He saw an obscure subterranean nexus in the human psyche that consciously rejects—yet counterintuitively remains attracted to—the inevitability of mortality, generating positive creative energy from thoughts of our inexorable extinction.

Freud called this impulse “death drive.” Famously, the Viennese inventor of psychoanalysis believed that literary artists were especially dialed into this particular vibe. In fact, he confessed that his research into various psychoanalytic concepts (such as the Oedipus complex) led him to realize that poets had “been there before me.” This was never truer than in the instance of John Keats. Anticipating Freud by a hundred years or so, it could be argued that Keats—along with his confrère Shelley—found poetic inspiration in death. When he declares in “Ode to a Nightingale” that “I have been half in love with easeful Death, / Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme …Now more than ever it seems rich to die …In such an ecstasy!” Keats is eroticizing mortality, domesticating fear by sublimating it into a lush lyric idiom. He instinctively grasped Freud’s idea of the paradoxical, life‑enhancing nature of the death drive.

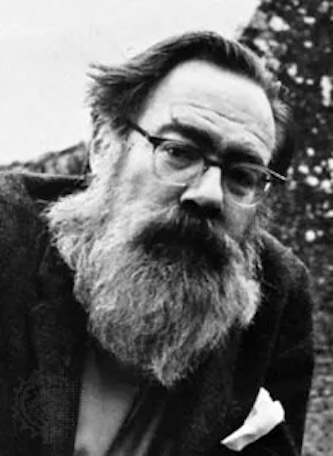

John Berryman (1914-1972), who is sometimes compared to Keats, was also half in love with death. He is usually associated with a clutch of midcentury writers lumped together in a poetic movement labeled the Confessional School—Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, W.D. Snodgrass, and Anne Sexton, among others. Amalgamating highly-charged emotional content with an uncompromisingly rigorous approach to technique, the Confessionals changed the course of American poetry. Over a short span of time—beginning with Heart’s Needle (1959) by Snodgrass, Lowell’s Life Studies (1959), Sexton’s To Bedlam and Part Way Back (1960), and Plath’s Ariel (1965)—there emerged a series of canonical volumes, books that earned critical plaudits for their honest and straightforward evocation of shockingly taboo subject matter.

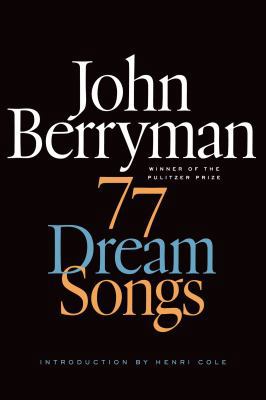

Arguably, however, Berryman’ s 77 Dream Songs (1964) epitomizes the Confessional style. Indeed, he outdoes himself — perhaps to top his contemporaries — and inundates the reader with a surfeit of paranoid psychosis, eclectic cultural allusions, and idiosyncratic preoccupations, all emanating from a fractured, unstable POV that, without warning or explanation, wildly jumps from one pronoun to another. “He,” “you,” and “I” are swapped around interchangeably — it is like watching a veteran street hustler working a game of three-card monte. Berryman smushed everything he could imagine into this syntactically chaotic format.

Because he never specifies where his chosen narrative voice is located, it is plausible that Berryman conceived these poems to radiate from some sort of an afterlife—Catholicism’s purgatory or Buddhism’s Bardo. Perhaps a region outside of normal time, in poetry’s eternal present. 77 Dream Songs reads like a demented Cubist painting, filled with shattered shards of reality. The space-time continuum has imploded, and the visual field has dissolved — everything everywhere has collapsed in on itself, perhaps to finally arrive at a zero point. Who sits at the centrifugal axis of the maelstrom? Berryman’s alter-ego anti-hero Henry, who, unlike Walt Whitman in “Song of Myself,” contains multitudes and profoundly suffers because of it.

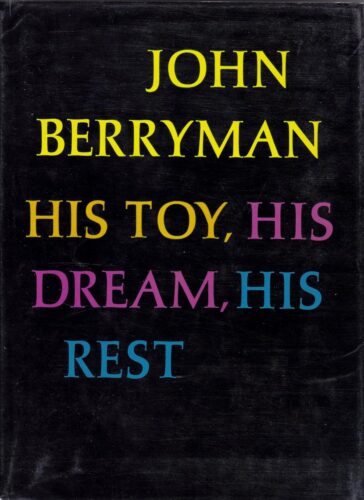

Henry, therefore, is the reader’s connection to Berryman. He is our Charon, the mythical boatman who ferries us across the River Styx, into the Hades of Berryman’s heart. Just as you might expect, there is a devil in this particular underworld. Given that Berryman’s lyrics are modified sonnets — extending the traditional structure from fourteen to eighteen lines—composed of (more or less) rhymed or slant rhymed free verse, arranged in sets of three stanzas, six lines each (6-6-6), it is no surprise that The New Yorker’s poetry editor Kevin Young calls these Songs “devil’s sonnets.” And, for almost sixty years, the only new Songs added to that initial collection in Berryman’s lifetime was 1967’s His Toy, His Dream, His Rest.

Twenty-four months after that, FSG fused them into a combined deluxe edition entitled The Dream Songs. Generations of devotees have come to this synthesized version to kneel at Berryman’s satanic altar. Word of mouth among believers has maintained a grassroots cult for The Dream Songs, an adoration that has not weakened, unlike the enthusiasm for other leading lights of the Confessional firmament, like Robert Lowell. Berryman’s passionate disciples continue to proselytize for their man, such as musician Nick Cave, who described Berryman as “an integral part of my world”. Cave went on to proclaim that The Dream Songs have “given me more pleasure than any other poems I have ever read.” Until now, there was no reason to believe that The Dream Songs wasn’t Berryman’s definitive last word on what was the essential poem of his life.

Twenty-four months after that, FSG fused them into a combined deluxe edition entitled The Dream Songs. Generations of devotees have come to this synthesized version to kneel at Berryman’s satanic altar. Word of mouth among believers has maintained a grassroots cult for The Dream Songs, an adoration that has not weakened, unlike the enthusiasm for other leading lights of the Confessional firmament, like Robert Lowell. Berryman’s passionate disciples continue to proselytize for their man, such as musician Nick Cave, who described Berryman as “an integral part of my world”. Cave went on to proclaim that The Dream Songs have “given me more pleasure than any other poems I have ever read.” Until now, there was no reason to believe that The Dream Songs wasn’t Berryman’s definitive last word on what was the essential poem of his life.

Until now, that is. The posthumous publication of Only Sing: 152 Uncollected Dream Songs proves that Berryman, even in death, remains a devil whose hands have not remained idle. Reminiscent of a compilation of studio outtakes, unearthed from deep in cobwebbed corporate archives, Only Sing feels as if it is a forget-me-not for the fans. These new Songs, uneven and repetitive, will disappoint, even mystify, discerning readers, particularly those who have been wavering on the fence. Several puzzling selections have been included here, even though they are missing a line or two. That brings them short of the minimum length required to qualify as a Dream Song. All in all, when taken together, the volume’s inconsistencies may confuse those who have yet to be introduced to Berryman’s distinctive voice. Newbies will wonder what all the fuss is about. And that will be a shame.

Only Sing’s editor, Shane McCrae, author of the poetry collection New and Collected Hell, clearly disagrees that harm will be done. This dedicated scholar lovingly excavated these previously unseen stanzas from storage boxes of Berryman’s papers, currently housed at the University of Minnesota, where he taught poetry for seventeen years until Berryman’s tragic suicide by jumping from a bridge into the Mississippi River in 1972. In his introduction, McCrae details the long process of selecting these one hundred and fifty-two specimens. For him, Berryman the poet is very much a Cause. Maybe this is part of the problem. Another pair of eyes — less star-struck perhaps — might have adjudicated the value of these verses differently. Yes, everything by a major writer deserves to be seen at some point. But, if the newly unearthed pages fall way short of the standard attained by what was published earlier, the proper thing to do is to place these “found” texts into an appendix at the end of a substantial anniversary edition, one replete with footnotes and the other required critical trimmings.

Here’s a hint of the missing perspective in Only Sing. An excerpt from Berryman’s very first Song: “All the world like a woolen lover / once did seem like on Henry’s side. / Then came a departure. / Thereafter nothing fell out as it might or ought. / I don’t see how Henry, pried / open for all the world to see, survived.” And these lines are from the 29th Song: “There sat down, once, a thing on Henry’s heart / só heavy, if he had a hundred years / & more, & weeping, sleepless, in all them time / Henry could not make good. / Starts again always in Henry’s ears / the little cough somewhere, an odour, a chime, // And there is another thing he has in mind / like a grave…All the bells say: too late.”

These pieces gleam with the fine-grained texture of burnished lines that have been diligently polished and meticulously cared for. There is nothing slapdash about them. We are directly confronted with Berryman’s great subject—death. And Freud couldn’t have tailored it any better than this pair of bespoke lines from Only Sing: “Death, however, my live friends, is the word; / death & sex.” He is more than a little in love with extinction. In truth, it would be difficult to find another modern writer who is more ruthlessly focused on the void that waits for us all — and who offers so little consolation. This insistence on facing finality manifests itself throughout The Dream Songs. It is what evokes considerable pain and yearning in the reader, lending these poems their ghostly grandeur.

Only Sing makes numerous other contributions to this obsession with mortality. To wit: “Death is a history / instead of an event.” And this: “It hardly matters but it has me sore. / Paler the dead grow, who had paled before. / It hardly seems fair. / Vaults are, are graves. I see it in your eyes” Again: “Crony Henry found a friend in Death: / the loss of consciousness;” “Feast on me, Death, if you like;” and “In time, in time, Henry will be towed away.” The latter is a bleak sentence. Its dark comedy deepens the pathos—we’re all just junkmobiles waiting for our turn to be hauled to the nearest chop shop, then crushed into a Rubik’s Cube. There are also memorable instances of Berryman’s vaunted linguistic sorcery: “Stood up like sins thin nerves, fled asleep, / followed it out of the language the word safe, / like peace gone Red. / Flickered along the floor reflected enigmatic sails. / Something cold dry vigorous, like coils, / is on its way to Henry’s only life.”

Only Sing, however, rarely sustains this level of concentration. It could be asserted that the process of diminishing returns had already begun with His Toy, His Dream, His Rest. Like a Hollywood franchise, Berryman followed what is demanded of a pop culture phenomenon — answering the call for sequels. The ultra-slim Only Sing feels like a serving of odds and sods. Despite the freshness of the initial 77 verses, by the time Berryman choogles on to the 380th Song, the old magic has waned. Did he drop the bucket down the same well too many times? Berryman knew it better than anyone else. Only Sing offers this clue: “Lying there…when he saw he had wild songs / further to utter, he wonders what belongs / afresh to these here gears // stuck in reverse.”

While each of The Dream Songs are numbered, and some have formal titles, none of the poems in Only Sing follow the same numerical precedent. According to McCrae, this change was an intentional editorial decision to not interfere with Berryman’s authorship. Complete hands-off neutrality, however, is not necessarily a good thing. Simply alphabetizing the order of these disparate remnants by first lines, for example, misses an opportunity to mold a random group of haphazard sketches into an elegant, harmonious, and infinitely more pleasurable reading experience. Indeed, things can get bumpy. Many of these stanzas have conventional titles (“Times, Fires, Gardens;” “Holyday I;” “To Phil”), while others are named after the poem’s first line. Adding to this melange is a suite of verses redundantly labelled “Four Dream Songs.” The arbitrary nature of this miscellany reinforces the provisional nature of the volume. What was the Master’s intent? The question haunts every page.

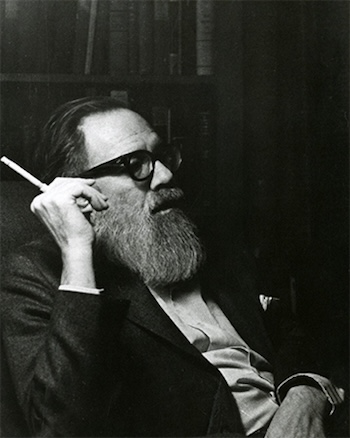

Poet John Berryman. Photo: courtesy of the University of Minnesota

Never fear, though, Berryman’s overdetermined idées fixes are present and fully accounted for. Nothing new or fresh comes along. Only Sing is filled with more of the same. There is divorce: “Could, who done always done nothing, God / persuade my ex-, once a month or so, / to toss me word of Poukie, / who is so little he can’t write one word.” Existential despair: “do you get the blues / and wonder what Life’s for” and “The happier you get the worse you feel.” Tributes and elegies for friends and others: “For Louis MacNeice;” “To Robert Lowell:” “To Dr. Carl Caspers.” And adultery: “Maris, my honey-love…Your husband is my doctor.”

There is a touch of the unexpected: Berryman’s exploration of gender fluidity. This macho womanizer surprises himself in the Songs by channeling the voice of a decidedly non-male presence: “Where does this other voice come from? Is a woman among us?” At one point, the poet articulates a powerful argument against non-binary prejudice: “In a concave dream Henry became a lady: / ‘Lady Henry’ everyone agreed / ‘is the best of ladies all.’ / Couvade & all that. Make-up’s tracery. / If you cut us, do we not bleed?”

Physical suffering triggers morbid self-reflection: “My fingers hurt, my feet are swollen, & I / am certainly to die.” Professionally despondent, Henry is trapped on the academic merry-go-round. Berryman is soullessly going through the motions: “teaching everybody in this State, / twice, many, they shift their asses fifteen feet / and Henry on Joyce becomes Henry on Dante.” God makes a predictable cameo, but He isn’t of much assistance: “Repeating his Semi-prayer to helpless God.” What used to mitigate the poet’s depression, “the devil’s drop”, the nineteenth century pejorative for hard liquor, is pitilessly undercut via terms from Alcoholics Anonymous, a program Berryman attended and wrote about in his uncompleted novel, 1973’s Recovery. He is well aware of other American writers who were corroded by the same addictive substance. The struggle for sobriety produces hallucinations in the midst of detoxing. What is worse—the disease or the cure: “Reduce booze. Reduce…booze? Reduce…booze…Frequent’ they mention / walls made of spiders, fights you cannot lose, / campaigns gainless & horrid, Scott Fitzgerald / and Edgar Poe.”

Berryman also delivers memorable put-downs; in particular, this high-hat dismissal: “My friend, you are a blowhard, one tires of you.” On the other hand, the needle on the creepy dirty old man meter goes into the red, now and then: “There’s a well-wisher in the bathroom now. Young. / She’s had all kinds of men, her roommate says, / But she’s never had a poet. Get ready. / You could maybe cement your fly shut.” But wholesome love gets a test run too: “Sing on, green love, whom harm had missed, moreless, / lost amongst buds & shoots, an inebriation of nature / came up, my dear, with You.” Nodding toward Berryman’s greatest soul mate, Shakespeare, there are stealthy riffs on the Bard of Avon and the Wars of the Roses: “My king-beam, carved, is older than the wars / upstaged in after time by turbulent Will / for the orange and nut crowd, / rosy wars.”

Then we come to Berryman’s Great Mistake. Infamously, after 77 Dream Songs was published, Berryman explicated his methodology. The poet speaks the plain truth on a scratchy recording that can be found on YouTube: “It’s about a man named Henry, an imaginary character, a white American, in blackface, namely a minstrel…in early middle age, who has suffered an irreversible loss, and enjoys many other difficulties…the cast of characters is large, but the most important one is an interlocutor of Henry’s, who calls him Mr. Bones,” which is a stereotypical role in minstrel shows. According to Berryman, then, he has, more or less, conceived of The Dream Songs as one big lexical minstrel entertainment. Picking a poem at random, here is some of the 60th Song: “After eight years, be less dan eight percent, / distinguish’ friend, of coloured wif de whites, / in de School, in de Souf. / —Is coloured gobs, is colored officers, / Mr. Bones. Dat’s nuffin? —Uncle Tom, / sweep shut your mouf.”

Then we come to Berryman’s Great Mistake. Infamously, after 77 Dream Songs was published, Berryman explicated his methodology. The poet speaks the plain truth on a scratchy recording that can be found on YouTube: “It’s about a man named Henry, an imaginary character, a white American, in blackface, namely a minstrel…in early middle age, who has suffered an irreversible loss, and enjoys many other difficulties…the cast of characters is large, but the most important one is an interlocutor of Henry’s, who calls him Mr. Bones,” which is a stereotypical role in minstrel shows. According to Berryman, then, he has, more or less, conceived of The Dream Songs as one big lexical minstrel entertainment. Picking a poem at random, here is some of the 60th Song: “After eight years, be less dan eight percent, / distinguish’ friend, of coloured wif de whites, / in de School, in de Souf. / —Is coloured gobs, is colored officers, / Mr. Bones. Dat’s nuffin? —Uncle Tom, / sweep shut your mouf.”

In 2017, Kevin Young and Paul Muldoon on The New Yorker: Poetry podcast discussed Berryman’s problematic use of blackface. Young characterized it as a “perverse reaction” to the Civil Rights movement of the ’50s and ’60s, which was taking place while Berryman was working on the Songs. “He seems to think,” Young explains, “that he’s getting actual Black vernacular language, which he’s not. He’s doing this, you know, mimicked dialect that was really a white invention of stage and screen. You had people like Hattie McDaniel, who is a wonderful actor, have to ‘learn’ black dialect in order to play a maid” in Gone With The Wind.

Why did Berryman do this? Zachary Leader, Saul Bellow’s recent biographer, writes that Berryman and Bellow collaborated on refining the blackface portions of Bellow’s 1959 novel Henderson the Rain King (“Nobody have evah see such a ahnimal”). Both authors were close friends, meeting during teaching gigs at the University of Minnesota. Berryman, in fact, co-dedicated 77 Dream Songs to Bellow. In addition, Berryman’s invention of Henry, so critics have suggested, was dependent on Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March (1953). Augie’s zany hijinks were not only an inspiration for the myriad unhinged exploits of the Songs, but Bellow’s use of Yiddish words along with the slangy lingo of Chicago’s streets. Dialect-wise, Bellow’s Augie came up with a successful literary strategy; Berryman’s blackface is troubling because it reeks of white privilege.

In the podcast, Muldoon proffers the excuse that this is “Henry saying these things, not Berryman.” However, at no moment in the Songs is there an attempt to critique the blackface persona, to condemn it as illegitimate. In fact, Berryman is proud of his blackface masquerade. As Young asserts, Berryman pats himself on the back for cracking the racial code. As a result, Henry is prohibited from saying nothing — he is a windbag Id. Except for interrogating the Songs’ use of blackface. Minstrelsy, a part of the history of American racism, remains untouched. These verses are filled with self-reproach, -hatred, and -recrimination. But no self-condemnation for using blackface. It just never occurred to Berryman.

What McCrae terms “verbal blackface” continues in Only Sing. The editor offers up a defensive exculpation of Berryman: “To contemporary readers, Henry’s use of verbal blackface might be off-putting, but it is essential.” Really? Blackface is never essential. Berryman, according to McCrae, “refused academic jobs in the South because he didn’t like how black [sic] people were treated there. I do not here suggest that Berryman was perfectly enlightened with regard to issues of race, but I do believe he recognized race relations as a…central problem for white Americans, the obstacle [Berryman’s]…hero must think his way through, and I believe he worked his way through toward justice.” McCrae does not offer any evidence to back up his argument. Given the seriousness of the issue, that is telling. McCrae’s decision to call this collection Only Sing is an aptly ironic choice. Berryman’s idea that we must sing through our suffering — it is a way to preserve our humanity — is inevitably compromised by his exploitation of blackface. The title is taken from a sequence that includes the offensive “Ise” minstrel locution for “I”—“Well, how we work it out? Don’t. Mr. Bones, Ise / prepared to come on heavy and strong / on your side. Only: sing.”

Poet John Berryman. Photo: courtesy of the University of Minnesota

Some readers have fallen in love with The Dream Songs. It is an achievement to be admired: there is nothing like them in American letters. But, for others, Only Sing is symptomatic of a corruption that runs throughout Berryman’s epic project. The choice of minstrelsy is not just a distraction that can be explained away by aficionados — it is impossible to excuse or forgive.

We need to reckon with the racism that contributed to the founding of the United States. Berryman’s lyrics surely represent America, but not how Shane McCrae thinks. Some of us continue to profess that, in our lifetimes, we have finally conquered racism. But The Dream Songs suggest that there is still reckoning to be done. Berryman was narcissistic (or myopically innocent) enough — during the civil rights era — to believe that blackface could serve as an aesthetic device. He articulated no doubt about that. He was in denial; and that is why The Dream Songs is a failure. And one with alarming significance today, given the rise of white Christian nationalism.

Damn you, Berryman. You are the devil. You could have been sublime. If only the poet had the courage to question his disastrous affinity for minstrelsy. These lines from Only Sing mourn his unfulfilled genius, what might have been: “Henry, running / with all his cunning / wither to hide / sprang to his side / himself, wearied & eyed / and tried to rest. // Henry at rest / tuckt up his legs / oval as eggs / poor Henry lay / some to this day / shake heads & say. // Down beat the sun / not on many but one / simplified, wretched / with hands outstretchèd/ begging them to hold / Henry’s place in the field of the Cloth of Gold.”

Michael Londra—poet, fiction writer, critic — talks New York writers in the YouTube indie doc Only the Dead Know Brooklyn (dir. Barbara Glasser, 2022). His poetry has been translated into Chinese by poet-scholar Yongbo Ma. “Time is the Fire,” published in DarkWinter Literary Magazine, is the prologue to his forthcoming Delmore&Lou: A Novel of Delmore Schwartz and Lou Reed. His review for The Arts Fuse, “Life in a State of Sparkle—The Writings of David Shapiro,” was selected for the Best American Poetry blog. He has appeared in Restless Messengers, spoKe, Asian Review of Books, The Blue Mountain Review, The Fortnightly Review, and Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, among others; and he also contributed the introduction and six essays to New Studies in Delmore Schwartz, coming next year from MadHat Press. Born in New York City, he lives in Manhattan.

“Uneven and repetitive” is exactly right. And I am not a “newbie” but I too “wonder what all the fuss is about.” I keeping hoping to find a good poem and am invariably disappointed. Berryman kept these out of the Dreams Songs for a reason. He knew he was singing off key. I consider myself a Berryman fan, but these poems should not have been published. Yet you wouldn’t know it from reading some of the positive reviews. So I was grateful for this one.

It’s worth noting that the aforementioned Berryman apologist Kevin Young is Black, and that, as editor of John Berryman: Selected Poems, for the Library of America’s American Poets Project, he makes mention, in passing, of Ralph Ellison, as “a friend of Berryman’s,” and quotes Ellison, in another context, on the meaning of blackface…. Young’s collection for LOA, with his introduction, is probably a better introduction to Berryman’s work than either The Dream Songs or Only Sing. Good luck!