Book Review: “Nobody’s Girl” — An Emotionally Wrenching Horror Story

By Helen Epstein

Virginia Roberts Giuffre’s memoir is a grim indictment of Jeffrey Epstein and the cruel and powerful men (most of them still unnamed in public) who were his clients.

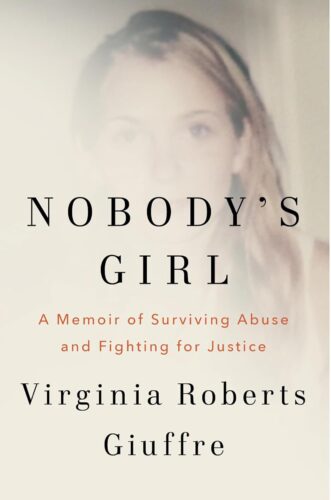

Nobody’s Girl: A Memoir of Surviving Abuse and Fighting for Justice by Virginia Roberts Giuffre. Knopf 2025, 400pp

How does a teenager get caught in the most notorious sex scandal in American history? Does she ever get out? Nobody’s Girl is a simple, earnest, often artless answer by one of the 1,000 girls and young women who were trafficked by Jeffrey Epstein. More than a memoir, it is a testimony to the shameful links between justice and social class, abusive parents, inadequate foster care, our police and legal institutions, and mass media. Excellently co-written with veteran journalist Amy Wallace, it is also a grim indictment of Epstein and the cruel and powerful men (most of them still unnamed in public) who were his clients.

How does a teenager get caught in the most notorious sex scandal in American history? Does she ever get out? Nobody’s Girl is a simple, earnest, often artless answer by one of the 1,000 girls and young women who were trafficked by Jeffrey Epstein. More than a memoir, it is a testimony to the shameful links between justice and social class, abusive parents, inadequate foster care, our police and legal institutions, and mass media. Excellently co-written with veteran journalist Amy Wallace, it is also a grim indictment of Epstein and the cruel and powerful men (most of them still unnamed in public) who were his clients.

Nobody’s Girl is painful to read and must have been excruciating to write. In addition to tracing her short life, Giuffre (1983-2025) asks: Was it my fault? My parents’ fault? Did I deserve it? Will I ever be free of it? As psychoanalyst Rachel Rosenblum wrote in Mourir d’écrire, many memoirists who survive trauma and write about it commit suicide. Virginia Roberts Giuffre became one of them at the age of 41. Three weeks before she killed herself, she had written to collaborator Amy Wallace: “In the event of my passing, I would like to ensure that Nobody’s Girl is still released. I believe it has the potential to impact many lives and foster necessary discussions about these grave injustices.”

Here’s the timeline:

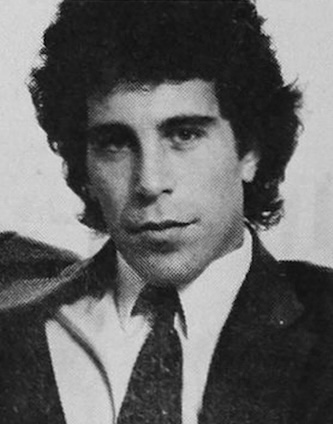

Jeffrey Epstein was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1953, dropped out of college, but charmed his way into a job at Manhattan’s Dalton School and then into an investment bank. By 1980, he was a familiar figure on the social scene, a Cosmopolitan Bachelor of the Month. In 1991, he met Ghislaine Maxwell, an Oxford graduate and daughter of UK media mogul Robert Maxwell.

After her father bought the New York Daily News, Ghislaine moved to NYC and began dating Epstein. By 2002, a Vanity Fair profile described her as his best friend. New York Magazine reported that Epstein employed over 150 people in various locations, including Palm Beach, Florida, where Maxwell recruited the girl who would become Virginia Roberts Giuffre to work for him.

Allegations of sexual assault against Epstein and Maxwell were first made in 1996 by then 25-year-old art student Maria Farmer. Epstein had bought one of her paintings and hired her as a renovation manager at his Manhattan townhouse, then offered her use of a studio in Ohio where his chief client, Leslie Wexner, lived. There, Farmer alleged, Epstein and Maxwell sexually assaulted her. Farmer managed to phone her father, who drove from Kentucky to rescue her. She reported them to the NYPD, then to the FBI. The NYPD told her it was out of their jurisdiction; she did not hear back from the FBI.

At the time, Virginia Roberts was a blonde, freckle-faced 12-year-old growing up in Loxahatchie, Florida. She describes it as a place of “renegade residents, loose land restrictions, and exotic animals” that was a world away from Palm Beach. Her father worked in construction and maintenance; her mother raised three children. Both parents were heavy drinkers. Dinner was “fishsticks, chicken tenders, anything that was on ‘special’ at the local Pantry Pride.” Jenna, as her family called her, packed her own school lunch: grape jelly on white bread.

In first grade, Jenna was a tomboy. When she was six, her father bought her a horse she named Alice after Alice in Wonderland. Around that time, her mother stopped putting her to bed and was replaced by her father. That was fine, she writes. “I loved my Dad. He’d taught me to ride Alice.”

Then her father began bathing Jenna. Then he began to visit her bedroom at night. “He told me I was his special girl, his favorite, and that this was his way of giving me extra love. He used his fingers at first. Then, his mouth. He called my private parts my ‘tee-tee’ and his penis his ‘pee-pee.’ It wasn’t long before he asked if I wanted to touch his genitals. I didn’t want to but he wanted me to. He was my father so I did.”

Jeffery Epstein in his late 20s. Photo: WikiMedia

Jenna soon developed severe urinary infections. When her doctor treated them and discovered her broken hymen, Mrs. Roberts explained that Jenna rode her horse bareback. The UTIs continued; it made it difficult for her to hold her urine in school, earning her the nickname “Pee Girl.” When Jenna came home with wet pants, her mother whipped her. Meanwhile, her father’s friend Forrest came up with the idea of swapping their daughters for sleepovers and they did. “Forrest was the first man to penetrate me with his penis,” she writes. “Not long after, my father did the same.” When she tried to tell her extended family, no one reacted.

Jenna’s refuge became the nearby Vinceremos Therapeutic Riding Center, where she mucked out stalls, shoveled hay, groomed horses, and helped disabled clients. She didn’t tell her motherly boss what was happening at home (“my dad had said if I ever told a soul, he would kill my little brother”). But when she was 11, Forrest’s wife discovered what the “sleepovers” entailed and told Mrs. Roberts. Her husband moved out and Jenna was sent to live with an aunt in California. But she ran away and was sent back to Florida. She ran away again, got into fistfights, cut class, smoked, and drank. After ninth grade, Jenna dropped out of high school and began having sex with a senior. “I thought I was taking back control of my life,” she writes, “trading on the only part of me that anyone seemed to care about — my body.”

Her mother committed her to a teen rehab center. In 1998, she ran away again and was picked up by a man in a limousine who owned an escort service. The man “gifted” her to a friend who, in 1999, was busted with Jenna in his bed. The police returned the now 16-year-old to her home. Mr. Roberts was then working at Donald Trump’s Mar-A-Lago, half an hour’s drive from Loxahatchie, maintaining the air conditioning units and tennis courts. In 2000, he got his daughter a $9-an-hour job as locker room attendant.

Jenna liked her white uniform and name tag and handing out towels in the quiet spa. She thought about becoming a massage therapist. She was at the front desk reading an anatomy book when a woman with a British accent asked, “Are you interested in massage?” A longtime club member needed one, Maxwell said, and if he liked her, he’d pay for her training. Jenna’s father drove her to Epstein’s mansion that evening and left. Maxwell led her up a spiral staircase whose walls “were crowded with photos and paintings of nude women” before entering a room with a massage table. A naked man lay face-down on top of it.

“Faced with Epstein’s bare backside, I looked to Maxwell for guidance,” Giuffre writes. “I had never gotten a massage before, let alone given one. But still I thought: isn’t he supposed to be under a sheet?” Maxwell instructed Jenna to wash her hands, then showed her how to warm lotion between her palms. She instructed Jenna to massage Epstein’s left foot, demonstrating on the right one. “I paid close attention, mimicking her as we moved higher, to Epstein’s thighs. When we got to his buttocks, I tried to glide past them, landing on his lower back. But Maxwell put her hands on top of mine and guided them to his rear. “‘It’s important that you don’t ignore any part of the body,’ she said. ‘If you skip around, the blood won’t flow right.’”

As the lesson continued, Giuffre writes, Epstein began to ask Jenna questions: Do you have siblings? Where do you go to high school? Do you have a boyfriend? Do you take birth control? When he asked about her first sexual experience, Jenna told him she had been abused by a family friend and spent time on the streets as a runaway. He said he liked naughty girls.

Mug shot of Jeffrey Epstein made available by the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Department, taken following his indictment for soliciting a prostitute in 2006. Photo: WikiMedia

“Then he rolled over on his back,” Giuffre writes, “and I was startled to see he had an erection. I’d seen men’s private parts before, obviously, but I hadn’t expected to see his.” Maxwell instructed Jenna to knead his pectoral muscles, “to push the blood away from his heart.” Then Epstein began masturbating. “This is the moment that something cracked inside me,” Giuffre writes. Maxwell peeled off her own clothes, undressed Jenna, and ordered her to fellate Epstein, then straddle him and clean him up. Afterwards, in his steam room, as she massaged his feet, Epstein lectured her about sweat lodges and the importance of making healthy decisions. “From that first meeting, Epstein wanted me to regard him as a mentor, not a predator,” she writes. Finally, Jenna was told to put her Mar-A-Lago uniform back on and was paid $200. “You did great,” Maxwell told her. Can you come back tomorrow?”

The butler drove her back to Loxahatchee in silence. Back home, she answered her parents’ questions briefly and spent an hour in the shower sobbing. “The worst things Epstein and Maxwell did to me weren’t physical but psychological,” she writes. “From the start I was groomed to be complicit in my own devastation. Of all the terrible wounds they inflicted, that forced complicity was the most destructive.”

By the time she began writing Nobody’s Girl, Virginia Roberts Giuffre had been interrogated by police, lawyers, other Epstein survivors, and the press. She had also had years of therapy that helped her understand trauma and PTSD. She and Wallace deliberately shaped her book, she writes, to help other victims get out of abusive situations and speak up. She also frames the dynamics of abuse by drawing a direct line between her childhood and Epstein-Maxwell. She is upfront about the allure of making good money, having a nice apartment, traveling to glamorous places, and being promised training in a career. But the most powerful lure, she writes, was the illusion of belonging to a family. “We were girls who no one cared about, and Epstein pretended to care.”

Maxwell taught her how to dress, behave, apply makeup, and observe table manners. Epstein often asked her to tuck him into bed at night, and gave her dating and dietary advice. “We’re proud of you,” he would say. And once in a while, he produced a photo of her beloved younger brother walking to school. He told her, “You must never tell a soul what goes on in this house.” And, “I own the Palm Beach Police Department, so they won’t do anything about it.”

Jenna turned 17 on August 9, 2000, and Epstein began to take her with him for trips on his private jet — to New York, London, Paris, California, New Mexico, and his private island. In nearby St. Thomas, Epstein suggested that she procure local girls. She warned each recruit what to expect, “but the fact that I issued warnings doesn’t diminish the ugly truth: when I targeted girls who were hungry or poor, I knew I was exploiting their vulnerabilities.… I know their pain and I will never get over playing a role in causing it.”

I had to take many breaks while reading Nobody’s Girl, which is filled with dozens of names, dates, and legal terms, in addition to being an emotionally wrenching horror story. I admired co-writer Wallace’s stamina and commitment and wondered who she was. Wallace, now 70, began her journalism career as assistant to New York Times columnist James Reston, then worked as an investigative reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the Los Angeles Times. Wallace not only interviewed Giuffre for four years, but read her notes and all court documents, interviewed key actors, fact-checked and organized the material, and created “breathers” that flash forward and back.

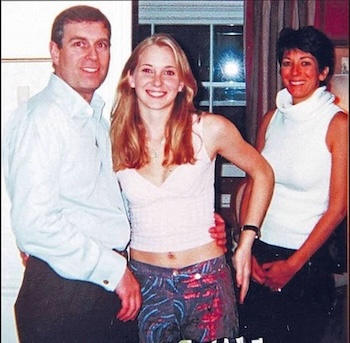

By 2000, she writes, Jenna was trafficked first to a man she calls Billionaire Number One and his pregnant wife, then to academics like the late Marvin Minsky of MIT and politicians like former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson. International clients included “a well-known former Prime Minister,” the French modeling agent Jean-Luc Brunel, and Prince Andrew. Epstein took the now-famous snapshot below with Jenna’s FunSaver camera. The photo was developed in West Palm Beach, the time stamp was later used as evidence in the legal proceedings.

Prince Andrew poses with Virginia Giuffre at the home of Ghislaine Maxwell (right), the now-convicted recruiter for Jeffrey Epstein’s sex-trafficking ring. Photo: courtesy of Giuffre

Before her 19th birthday in 2002, Epstein asked her to have a child for him and Maxwell — a demand that, she writes, made her determined to escape. She told them she would have the child after they delivered on their promise to pay for her to be trained as a massage therapist. They enrolled her at ITM, a massage school in Chiang Mai, Thailand, where she could be certified in eight weeks. Maxwell booked a flight and four-star hotel, and told Jenna to recruit and bring back a girl that Epstein had identified.

At this point, the narrative tone becomes upbeat: Jenna loved TMI, as well as the after-hours partying. After two weeks she dropped out to marry 26-year-old Australian and spiritual seeker Roberto Antonio Giuffre, who proposed after 10 days. “Robbie” was the son of Sicilian immigrants to Australia. When the couple arrived in Sydney, Jenna took her husband’s name and they got an unlisted phone number.

Once off the Epstein payroll, Jenna’s account of starting a normal life is forthright and sometimes funny. Her warm, welcoming in-laws ran a catering business; she was anorexic and had no idea how to cook, clean, shop, or manage a household. Robbie worked long hours and had a temper. Jenna had no work permit, was suspicious of everyone, and suffered from PTSD. With prior sexual partners she had been “a sort of zombie,” trained to perform while ignoring her own desires. The first time she slept with Robbie, Giuffre writes, she jumped out of bed immediately afterward to bring him a warm washcloth. Oral sex made her uneasy and triggered flashbacks that she tried to hide, but then her husband, learning new information in dribs and drabs, began to ask more and more questions. Fragments of her former life began turning up in Australian media: an actress on TV who was an Epstein girl; a Vanity Fair profile of Epstein.

After being told that she might never be able to have children, Giuffre gave birth to a son in 2006 and was pregnant with their second when the phone rang and a familiar voice said “Jeffrey’s being investigated. Have you been contacted?” (Reading this, I actually shuddered) “If you need legal help, we’re here to help you.” Then Epstein called up. Then the FBI. Although Jenna did not yet know the details, in 2005, a Palm Beach mother called the police after overhearing a 14-year-old talk about a man who paid her for sex. Detectives interviewed many more underage girls and a Palm Beach County grand jury indicted him on a charge of solicitation of prostitution, but, after a series of legal maneuvers and a light jail sentence, US attorney for the Southern District of Florida Alexander Acosta approved a plea deal granting Epstein immunity from all federal criminal charges.

In April 2007, at 24, Jenna gave birth to her second son, who was neurodivergent. Through counseling for him, she found a therapist for herself and, after being contacted by the US Department of Justice in May, 2009, she filed suit against Epstein as “Jane Doe 102.” The complaint read, “Plaintiff has suffered a loss of income, a loss of the capacity to earn income in the future, and a loss of the capacity to enjoy life. These injuries are permanent in nature.” That November, she signed a secret settlement with Epstein’s lawyers for $500,000, an amount based on the average price of homes in a suburb two hours from Sydney where she and Robbie wished to buy a house.

Virginia Giuffre holds a picture of her younger self. Photo: Wikimedia

In 2011, Sharon Churcher of the British tabloid the Daily Mail tracked her down and Giuffre told her about the snapshot of herself and Prince Andrew. The birth of her third child — a daughter — brought her closer to going public with her story. “I adored my sons, but their births hadn’t sent me on a trip down memory lane. Ellie’s did. Looking at her, I could picture myself as the vulnerable girl I’d once been.” Then, British News of the World had published a photo of Epstein and Prince Andrew walking in Central Park under the headline “Prince Andy and the Paedo.” Reprinted in Australia, it was the last straw. In March of 2011, at 26, Virginia Giuffre became the first Epstein victim to identify herself by her real name in the Sunday Mail.

In her first naïve encounter with tabloid journalism, she was paid $164,000 and reaped a whirlwind of more press, paparazzi, stalkers, and the FBI. Once again, she was interrogated and shown photographs of men who had abused her. Her husband was present and, hearing new details, lashed out at her and the agents. Over the next decade, Giuffre writes, the couple received millions of dollars from lawsuits against Maxwell, Andrew, the Epstein estate, and JPMorganChase. She established a nonprofit organization called Speak Out, Act, Reclaim (SOAR) to support victims of sex trafficking, but she was widely criticized for settling with Epstein. Going public strained the Giuffre marriage, as did media coverage calling Jenna a “whore,” death threats, and mysterious break-ins. She had been self-medicating since adolescence and she continued to do so with a variety of drugs.

The family moved several times. She found support in her trusted psychotherapist Judith Lightfoot, her growing group of “survivor sisters” like Annie and Maria Farmer; her lawyers David Boies, Brad Edwards, and Sigrid McCawley; and the #MeToo movement that gained strength in 2017, as hundreds of women, investigative journalists, lawyers, and judges addressed sexual abuse and initiated lawsuits at Fox News, Uber, in Hollywood, and in sports, especially the more than 500 girls and young women affiliated with USA Gymnastics, Michigan State University, and the United States Olympic Committee.

Even in a gated community in Cairns, Australia, she could not escape international news. In 2017, Donald Trump became President and appointed as his Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta, who had arranged Epstein’s Palm Beach plea deal when he was US attorney for the Southern District of Florida. At the same time, Giuffre learned that investigative journalist Julia K. Brown of the Miami Herald newspaper had uncovered 80 Epstein victims and written a multipart series accompanied by photos and videos, allowing them to speak directly to readers. Then, the Southern District of New York opened an investigation into Epstein and, in July of 2019, he was arrested on federal charges of sex trafficking. The next day, Acosta resigned from Trump’s cabinet.

On August 9, 2019, Giuffre turned 36. The following day, 66-year-old Epstein was found dead in his cell in Manhattan. New York’s chief medical examiner ruled the death a suicide by hanging. A “media frenzy” ensued in which her most important interview, Giuffre writes, was with 60 Minutes Australia, as part of an extensive segment that included several lawyers and survivors. She watched with her husband and two sons, then 12 and 13. She wanted to avoid their being “blindsided” by kids who might have heard she had been on TV and for them to understand what she had been fighting for. “They’ve known for a long time that something bad happened,” she told her husband. “I think they are old enough now to understand.”

Virginia Giuffre appearing in the 2020 Lifetime documentary series Surviving Jeffrey Epstein. Photo: YouTube

In November, Prince Andrew appeared in a disastrous interview on the BBC’s Newsnight. Circumstances of Epstein’s death led to numerous conspiracy theories.

Giuffre flew almost everywhere she was invited to testify and her husband could see the toll it was taking. “When someone comes home from fighting a war,” he told her, “they heal, they get therapy…. How are you supposed to get better if you never come home from the war?”

In spring of 2020, the entire family took a vacation in Butterfly Valley just as the Covid epidemic began. In a series of accidents, Giuffre developed meningitis, was hospitalized, and then broke her neck. Immobilized and taking heavy pain medication, she followed Netflix’s four-part version of the Epstein story and newspaper headlines such as “Prince Andrew’s Accuser Was a Prostitute Paid Off by Jeffrey Epstein.” Yet she continued her legal and media activities. In June 2021, she flew to Paris to give a deposition against modeling agent Jean-Luc Brunel, who had gone into hiding following Epstein’s death. When found, he was arrested, charged with the rape of minors, and jailed.

Virginia Giuffre continued to have serious health problems, but on August 9, 2021, her birthday, she sued Prince Andrew for violating New York’s Child Victims Act. “As I turned thirty-eight,” she writes, “I realized that I had spent the second half of my life recovering from the first … and I was still fighting for justice. I’d come a long way, but I had yet to feel anywhere near whole. I wondered if that feeling would ever come.”

That November, she did not fly to NYC for Ghislaine Maxwell’s trial there, but followed courtroom tweets from Australia. Maxwell, too, had gone into hiding after Epstein’s death but, when found, was convicted by a jury on five sex trafficking-related counts and was sentenced to 20 years in prison. One of the lead prosecutors was Maurene Comey.

In January 2022, Prince Andrew’s time was up. Queen Elizabeth stripped him of his royal and military titles. The next month, a settlement with Giuffre was announced, unleashing another media blitz. Three days later, in Paris, Jean-Luc Brunel was found dead by hanging in his jail cell.

Meanwhile, ordinary life in Australia went on for Giuiffre, especially with the parents of her children’s friends. When a mother dropping off her son at her door gasped, “Oh my God, it’s you! We don’t have to talk about it. It’s probably embarrassing.” Giuffre replied, “No it’s not embarrassing.”

Giuffre yearns, she writes in her last chapter, for a world in which “predators are punished, not protected; victims are treated with compassion, not shamed; and powerful people face the same consequences as anyone else…. I mean, seriously: Where are those videotapes the FBI confiscated from Epstein’s houses? And why haven’t they led to the prosecution of any more abusers? Imagining it is the first step … I picture a woman who — having come to terms with her childhood pain — feels that it’s within her power to take action against those who hurt her. If this book moves us even an inch closer to a reality like that — if it helps just one person — I will have achieved my goal.”

The investigation continues as you read. Rest in peace, Virginia Roberts Giuffre.

Helen Epstein is a veteran journalist who wrote about her own experience with childhood sexual abuse and its consequences in The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma. She is not related to Jeffrey.

Tagged: "Nobody's Girl", Amy Wallace, Ghislaine Maxwell, Jeffrey Epstein, Prince Andrew

This is a powerful and deeply moving review. The care taken to contextualize Virginia Giuffres story while honoring her voice and courage is remarkable. An essential difficult read that underscores how justice power and trauma intersect and why these stories must continue to be told.

Thank you.

Compassionate review of an all too frequent horror story.