Book Review: “Racebook” — Internetting While Black

By Preston Gralla

One of today’s most distinctive intellects wrestles with the internet and all its messy consequences.

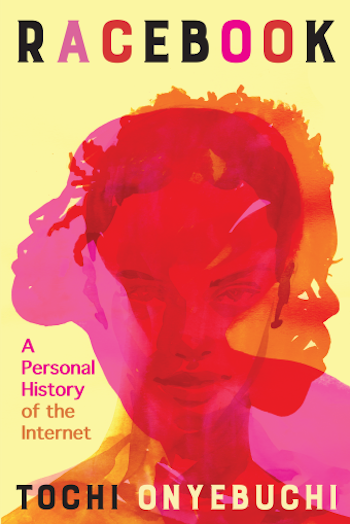

Racebook: A Personal History of the Internet by Tochi Onyebuchi. Grove Atlantic, 256 pp, $27

Tochi Onyebuchi doesn’t waste any time getting to the question at the core of this memoir about coming of age on the internet. On its very first page he asks in big, bold type: “Is this a race book?”

Tochi Onyebuchi doesn’t waste any time getting to the question at the core of this memoir about coming of age on the internet. On its very first page he asks in big, bold type: “Is this a race book?”

In large part, the answer is yes. It’s inescapable that the son of Nigerian immigrants would view the internet at least partially through the lens of race. America’s racism leaves no other choice.

Not that he started out looking at the online world that way. Initially, the internet was for him a place apart, an idealistic playground where one could follow one’s interests wherever they may lead and find others who share them. He recalls, “I raved online about the things I loved in the hopes that enough people would love them too…. We did, after all, flock to the early internet to make fan pages for the anime and musicians we loved.”

But the internet didn’t stay a place apart for him for long. Onyebuchi soon found that race is as inescapable there as it is in the real world. He remembers, “At some point during my time on the internet, the demographic markers I thought I’d shed whenever I logged on had latched back on to me. Gone was the faceless, skinless enjoyer of things, the amorphous yet singular netizen whose only color was that of the internet’s neon signs glowing on me.”

“Suddenly, it seemed tremendously important that I was Black.”

It became even more essential after George Zimmerman was found not guilty of killing the young Black man Trayvon Martin 2013. Onyebuchi writes that at that moment millions of Black people “were suddenly having to do battle in Facebook comments threads with people they’d known all their lives, people they’d assumed would know which side was right and which side was wrong, people they realized had never truly known them at all.”

From there, Onyebuchi traces the importance of race online through the Afrofuturism movement and up until today. He writes especially powerfully about how Black people have used the internet to fight for themselves, given that the government and other people won’t.

Onyebuchi writes, “An old African proverb states, ‘Until the lion learns how to write, every story will glorify the hunter.’ And here we are, finally, having snatched the pen, the tablet, the laptop from the hunter and typed out, with our claws, the true story of the savannah. Oppression seeks to pulverize the possible, to atomize hope, to granulate not only dreams but the very act of dreaming. What control does one have over the slave, the sharecropper, the convict in a capitalistic enterprise if they can imagine another Now, if they can build, in the cathedral of their mind, an After?”

The internet allows them, he says, to better imagine that Now and build that After.

But to call this book only a “race book” sells it short. Onyebuchi’s insights into the consequences of the internet for both bad and good transcend race. The volume isn’t a single unbroken narrative; instead, it is a series of essays that trace his online use and what that means to him from teen years through adulthood and today. Given that Onyebuchi has an undergraduate degree from Yale, an MFA in screenwriting from NYU, a law degree from Columbia, was a digital intern at Marvel Comics, became a lawyer specializing in civil rights law, and is now a science fiction and fantasy author, he has a lot to say about far more than race,

So don’t read this book only for Onyebuchi’s personal insights about the online world and race. Read it for a close-up look at one of today’s most distinctive intellects wrestling with the internet and all its messy consequences.

Preston Gralla has won a Massachusetts Arts Council Fiction Fellowship and had his short stories published in a number of literary magazines, including Michigan Quarterly Review and Pangyrus. His journalism has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, USA Today, and Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, among others, and he’s published nearly 50 books of nonfiction which have been translated into 20 languages