Book Review: Rich Lives in the Musical Margins — “Dancing With Muddy” and “Before Elvis”

By Noah Schaffer

Two good reads: Boston harmonica player Jerry Portnoy’s memoir is an unflinching look at life as a sideman musician; the other is a history that shows how, without the Black stars he heard in Memphis, there would have been no Elvis or rock ’n’ roll as we know it.

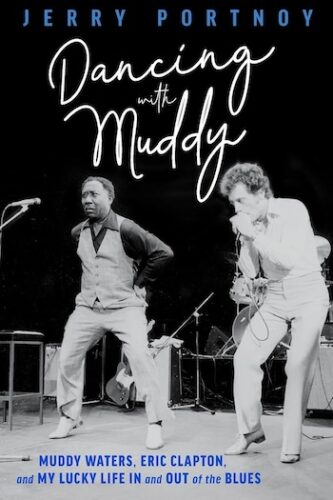

Dancing With Muddy: Muddy Waters, Eric Clapton, and My Lucky Life In and Out of the Blues by Jerry Portnoy. Chicago Review Press, 282 pages, $19.99

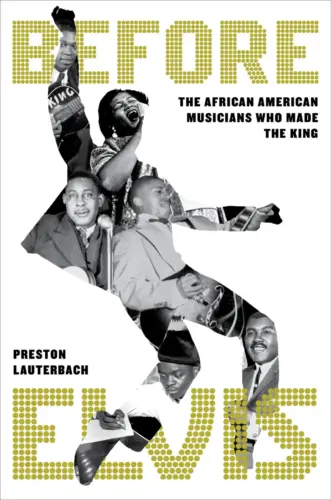

Before Elvis by Preston Lauterbach. Da Capo, 288 pages, $15.99

Most blues and pop music histories adopt “the great man theory” and focus on the biggest names in music. Two worthwhile new books take a refreshing departure from this approach. Boston harmonica player Jerry Portnoy’s Dancing with Muddy is an unflinching look at the life of a sideman musician who spent years with famous names, Muddy Waters and Eric Clapton among them Historian Preston Lauterbach’s Before Elvis examines the under-appreciated R&B, jazz ,and gospel artists who inspired the King.

Most blues and pop music histories adopt “the great man theory” and focus on the biggest names in music. Two worthwhile new books take a refreshing departure from this approach. Boston harmonica player Jerry Portnoy’s Dancing with Muddy is an unflinching look at the life of a sideman musician who spent years with famous names, Muddy Waters and Eric Clapton among them Historian Preston Lauterbach’s Before Elvis examines the under-appreciated R&B, jazz ,and gospel artists who inspired the King.

Portnoy penned his remarkably engrossing and well-written memoir without a ghost writer. An accomplishment befitting an artist who, despite growing up in the blues capital Chicago, was already 24 before he ever picked up the instrument that would take him around the world.

Even if he had never played music, Portnoy’s early years make an interesting read. He was raised in the hustle and bustle of Chicago’s Maxwell Street, where Jewish merchants and Black blues pioneers mingled. He bailed on college to shoot pool, spending his days in dark billiard halls frequented by the likes of Minnesota Fats.

Portnoy details how he would play Chicago’s Black juke joints at night while supporting himself with a day job as a jail counselor. A combination of talent and luck propelled the harmonica player into joining the Muddy Waters band in 1974. At that point, the legendary blues guitarist had successfully transitioned from juke joints to mainstream rock clubs. He carried a top-notch band that also included pianist Pinetop Perkins, guitarist (and Brookline native) Bob Margolin, Luther “Guitar Jr.” Johnson (who would go on to be based in New England for years) and drummer Willie “Big Eyes” Smith.

But, while life with Muddy allowed Portnoy to play to adoring audiences at home and abroad, it was far from a cushy gig. Some of the most revealing parts of Dancing with Muddy look closely at the business relationship that Waters, who was raised in poverty in Jim Crow Mississippi, and his hard-nosed manager Scott Cameron had with the backing band. Even as Muddy became an international cultural treasure, his musicians were paid a paltry amount, after their time and road expenses had been accounted for. Portnoy points out that the blues as a genre had long been defined as leader/sideperson arrangement. That dynamic led Cameron to view his star’s contracted employees as largely expendable. In a dramatic turn of events, Portnoy’s modest financial demands led to his firing from the unit after six years, and the rest of the band decided to quit in solidarity.

This departure led to a relocation to Boston, where Portnoy’s attempts at starting over as a leader of his own band were hampered by the backstabbing and double dealing that thrives in the insular blues world. The harmonica player fires off some especially unkind words for guitarist Ronnie Earl in the wake of a short-lived stint Portnoy had with the band Ronnie Earl and The Broadcasters. (He also engages in some score settling when describing a very brief and unhappy period with Cyndi Lauper.)

Professional and financial redemption comes with the arrival of Eric Clapton, who hired Portnoy for a string of blues-centered performances. In recent years, Clapton has come under fire for peddling anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, which in turn reminded many of racist positions he took in the ’70s. In his memoir, Portnoy (whose own social media presence is ceaselessly anti-MAGA) avoids talking about Clapton’s politics or those of any of his other bosses. To him, Clapton was a bandleader who played well, paid well, and treated his musicians with respect. (The two recently reunited when Clapton played Boston’s TD Garden.)

Portnoy’s unusual candor helps make his story of a life in the blues as honest as it is readable.

A decade before Woodstock-generation musicians like Portnoy started going deep into the blues, another white artist, Elvis Presley, changed the world by fusing the R&B he heard in Memphis with hillbilly music. Preston Lauterbach’s Before Elvis examines the careers of several of the Black artists whose songs Elvis took to the top of the charts, deftly weaving together how they influenced Elvis as well as how being covered by the King did – or didn’t – change their lives.

A decade before Woodstock-generation musicians like Portnoy started going deep into the blues, another white artist, Elvis Presley, changed the world by fusing the R&B he heard in Memphis with hillbilly music. Preston Lauterbach’s Before Elvis examines the careers of several of the Black artists whose songs Elvis took to the top of the charts, deftly weaving together how they influenced Elvis as well as how being covered by the King did – or didn’t – change their lives.

Perhaps the most well-known figure in Before Elvis would be Big Mama Thornton, the hard-living “Hound Dog” vocalist who got her start on the chitlin’ circuit but later became a mainstay of the college-centered blues revival in both Europe and the United States until her death in 1984.

Painting a more vivid picture of Thornton than what was supplied by a recent public television documentary about the singer, Lauterbach describes her start as a show-stopper of a performer with the influential Johnny Otis revue. He also goes into how she was an eyewitness to the death of singing sensation Johnny Ace by a self-inflicted gunshot wound on Christmas Day, 1954, a traumatic event that remains shrouded in mystery and conflicting reports to this day.

Thornton never enjoyed the kinds of riches that Presley garnered, although she did see some songwriting royalties after Janis Joplin covered her composition “Ball and Chain.” Watching the astronomical growth of Presley’s fame and wealth stung, but Thornton was determined to maintain her life and career — she went out on her own terms.

Thornton’s original recording of “Hound Dog” was cut for the notoriously ruthless Houston label owner Don Robey’s Duke/Peacock empire. (There’s an effort underway to rehabilitate the tarnished image of Robey. Yes, being a successful Black entrepreneur during Jim Crow was no small feat, but it came at great cost to many of the label’s artists, who insist they were never paid for their music.) Another Robey act, Little Junior Parker, contributed “Mystery Train” to the early Elvis repertoire.

Timing might be one reason Parker never reached the white college audiences that Thornton crossed over to – he died in 1971. Another reason is that his schedule was already full, thanks to his status as a major performing artist in Black venues. Now somewhat forgotten, Parker was the longtime touring partner of Bobby “Blue” Bland, and he was scoring R&B smashes like “Driving Wheel” years after he recorded “Mystery Train.” Flexible enough to change with the times, Parker made some great funk and soul records at the end of his life. (These are just a few of the excellent recordings that readers will learn about while reading Before Elvis.)

Another landmark early Elvis recording, “That’s All Right, Mama,” was originated by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, whose story is perhaps the saddest in the book. He was swindled out of his publishing rights and ended up dropping out of the public eye to become a flatbed truck driver. Time passed and he eventually benefitted from the recording and managerial expertise of Bob Koester of Delmark Records and Dick Waterman, the Cambridge-based promoter and manager.

Thornton, Parker, and Cruddup originated some of Elvis’ most famous early recordings. But Lauterbach also focuses on more obscure, but equally fascinating figures, like Reverend Dr. William Herbert Brewster, whose preaching so inspired Elvis that the young singer was one of the few white faces in Brewster’s Memphis congregation. Most jazz fans know of the brilliant-but-troubled pianist Phineas Newborn. Before Elvis chronicles both his story and that of his guitarist brother Calvin, who became a good friend of Lauterbach. Some readers may decide to take some of Calvin’s more outlandish Elvis-related claims with a grain of salt. but they make for a good read, as does this examination of how, without the Black stars he heard in Memphis, there would have been no Elvis or rock ‘n roll as we know it.

Noah Schaffer is a Boston-based journalist and the co-author of gospel singer Spencer Taylor Jr.’s autobiography A General Becomes a Legend. He also is a correspondent for the Boston Globe, and spent two decades as a reporter and editor at Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly and Worcester Magazine. He has produced a trio of documentaries for public radio’s Afropop Worldwide, and was the researcher and liner notes writer for Take Us Home – Boston Roots Reggae from 1979 to 1988. He is a two-time Boston Music Award nominee in the music journalism category. In 2022 he co-produced and wrote the liner notes for The Skippy White Story: Boston Soul 1961-1967, which was named one of the top boxed sets of the year by The New York Times.

Tagged: "Before Elvis", "Dancing with Muddy", Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, Big Mama Thornton, Elvis Presley, Jerry Portnoy, Little Junior Parker, Muddy Waters, Preston Lauterbach, blues