Book Review: “Razzle Dazzle” Minus Some of the Sparkle — John Lahr Profiles the Stars, and Himself

By Robert Israel

If John Lahr could learn, even in his eighties, to cut back on his own self-adoration and stop being so damned starstruck, the razzle in his profiles would dazzle all the more.

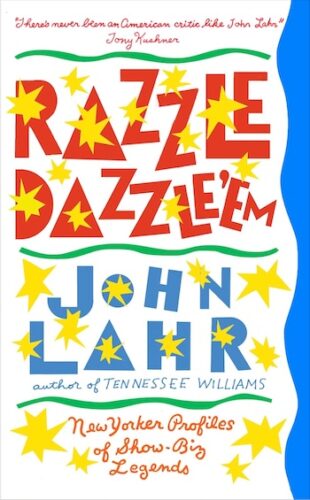

Razzle Dazzle ’Em: New Yorker Profiles of Show-Biz Legends by John Lahr. Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, 400 pages, $29.99

When I attended author and New Yorker theater critic John Lahr’s sold-out talk at Provincetown’s high school auditorium in 2014 – he was guest speaker at the 9th annual Ptown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival – I caught a glimpse of him onstage stifling a yawn. In that one instant, the resemblance to his late father Bert Lahr (the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz) was jolting. Instead of seeing a portly theater critic discuss his weighty biography on Tennessee Williams, what unspooled before me was a scene from the movie wherein his dad, the Cowardly Lion, yawns, rubs his eyes, and succumbs to the sleep of the poppies.

When I attended author and New Yorker theater critic John Lahr’s sold-out talk at Provincetown’s high school auditorium in 2014 – he was guest speaker at the 9th annual Ptown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival – I caught a glimpse of him onstage stifling a yawn. In that one instant, the resemblance to his late father Bert Lahr (the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz) was jolting. Instead of seeing a portly theater critic discuss his weighty biography on Tennessee Williams, what unspooled before me was a scene from the movie wherein his dad, the Cowardly Lion, yawns, rubs his eyes, and succumbs to the sleep of the poppies.

John Lahr, now aged 84, lives in London. He has inherited his father’s owlish face, puffy eyes, and heavy jowls. He’s only missing one essential element: humor. Bert Lahr was a professional funny man. Many considered him a comic genius. His son John — not so much. In person and in print, he comes off humorless, his writing a ponderous bore, heavily flavored with mordancy. Could that be because he’s so self-impressed? Consider this quote from his profile of playwright Wallace Shawn (from a New Yorker profile): “We both were sons of cultural royalty: his father [New Yorker editor William Shawn] was a king of high culture, mine of low culture. We’d lived on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, attended Ivy League colleges, done postgraduate work at Oxford, gone into theatre.” There is no touch of self-effacement there, nor even an attempt to deliver one.

Lahr was hired at the magazine by then-editor Tina Brown, in 1992, and given license to produce “a new kind of criticism, theater from the inside.” He has been recognized for producing outstanding work by being feted with not one but two George Jean Nathan awards. He also holds the dubious honor of being the only theater critic to have received a death threat for filing a negative review of a Stephen Sondheim musical.

Lahr defines a theater review as a work whose purpose is more than just a “consumer function.” It’s not enough to let readers know whether such-and-such shows are worth seeing or not. Lahr considers those reviews to be “shallow.” “I was critical, and remain critical, of the New York Times and how all it all hangs on them,” he has said. “It’s a corrupt system.” This propelled him on a crusade to change the nature of theater criticism, a quest from which he is now retired. (Helen Shaw, a Harvard grad who has more than once boasted about her pedigree in print, now serves as theater critic for The New Yorker).

This brings us to a consideration of his lengthy and intriguing show business profiles written for The New Yorker, which have been made available in several collections. The latest, Razzle Dazzle ’Em, takes its title from the musical Chicago, specifically the hotsy-totsy number performed by shyster lawyer Billy Flynn as he instructs inmate Roxie Hart on how to use her acting skills to convince a jury she’s not a murderer.

The book, despite my misgivings about the two-ton weight of Lahr’s ponderous prose, is well worth reading. The profiles, an assemblage of pieces that appeared from the early 2000s until 2022, include portraits of stage and film actors Helen Mirren, Sean Penn, and Viola Davis, as well as directors Mike Nichols and Sam Mendes, among others.

What makes Lahr’s work compelling is the sheer amount of man-hours that go into creating one. He’s a gold miner, sifting through tons of wet silt, searching for gems: “A profile nowadays is a sort of mini-biography of up to ten thousand words which takes three or more months to report and to write,” he tells us. Of course, he has the fact-checking and copy-editing staff of The New Yorker at his disposal, charged with culling through “about a thousand transcribed pages” of material. And, he notes, his chosen big name subjects “have to agree to the magazine’s unusual journalistic terms: a minimum of six hours of interviews, meet-ups in at least three different settings, and some psychological scrutiny.”

Among the best of these profiles is one devoid of egotistical pretension altogether. Its subject, actress Viola Davis, wouldn’t have it any other way. Davis, the daughter of a stableman and of mother who was beaten and battered at home, grew up not far from my hometown of Providence in Central Falls, Rhode Island. It was from there that Davis overcame her considerable hardships. She went on to succeed brilliantly, winning an Academy Award for her performance in the movie adaptation of August Wilson’s Fences (Arts Fuse review).

There is another reason that the Davis profile works so well: Lahr doesn’t wallow in his usual case of starstruck awe. In his profile of actor Al Pacino, for instance, he is overwhelmed by Pacino’s abundance of “razzle-dazzle,” and peppers his prose with mawkish and fawning praise. Not many words are spent on the fact that Pacino, like Viola Davis, came from impoverished roots in New York.

This said, the most compelling profiles in Razzle Dazzle ’Em reflect Lahr’s commitment to journalistic integrity. He exposes actors – who are adept at manipulating audiences to believe they are someone else—in ways that make it plain that, in some ways, they are just like us folks. Coming up with portraits like that is a Herculean task, and Lahr succeeds more often than he fails. If he could learn, even in his eighties, to cut back on his own self-adoration and stop being so damned starstruck, the razzle in his profiles would dazzle all the more.

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Back in the mid-’90s, John Lahr called me (he had been egged on by A.R.T. honcho Robert Brustein) and immediately launched into a tirade in which he castigated me about an article I had just written (for a now defunct New York theater magazine) that critiqued his and Tina Brown’s creation of the corrupt “review-profile” — the critic combined an inevitably all-praise review with a starry-eyed profile of the playwright (or performer) in the same piece.

I had called Lahr out and he was upset at being caught. He didn’t have much of a defense. I wish I had recorded the fulmination. I will never forget that, as Lahr rampaged, he kept saying “you had better not have cut any of my book sales!” I don’t think I had anything to do with it, but that bastardized form of journalism — critic and publicist lip-locked — died a well-deserved death when Brown left The New Yorker.

With champions of theater criticism like Lahr, who needs enemies?

His brilliant writing on Buster Keaton — who he knew– and how parental abuse generated his comic impassivity has stayed in my mind.

After criticizing John Lahr for inserting himself into his writing, such as comparing his own upbringing with Wallace Shawn’s, it’s odd that Israel produces this sentence towards this end of his review: “[Viola} Davis, the daughter of a stableman and of mother who was beaten and battered at home, grew up not far from my hometown of Providence in Central Falls, Rhode Island.”

And what about his stating that “The book, despite my misgivings about the two-ton weight of Lahr’s ponderous prose, is well worth reading.”

Whiplash.

Mr. Frassier, thanks for your note.

A reviewer should look for the positive and negative in a writer’s work.

BY inserting a mention of my hometown of Providence, a well-known city, in the sentence about Ms. Davis, I meant to help orient readers to the little known nearby town of Central Falls (literally the smallest city in the smallest state), and to say, I, too, lived with families like hers as neighbors whilst growing up there.

As for Lahr calling himself “cultural royalty,” well, that’s just plain snobbish. Maybe that’s why he prefrs to live in the U.K., since they seem to embrace royalty there on a daily basis.

There are excellent aspects to Lahr’s work, and I mention these, and there are some really heavy-handed aspects, too. It’s not black and white. His work is worth reading, even if he writes with a heavy hand. A reader has to sift through that, and if a reader wants to do the work required, they should know what they’re in for.

A fact-checker from The New Yorker once called me to confirm information about the Chicago try-out run of the original production of The Glass Menagerie. I was asked about critic George Jean Nathan’s alleged involvement with actor/director Eddie Dowling’s attempts to revise the play. Lahr had recently completed Lyle Leverich’s biography of Williams, and the questions the fact-checker asked me reminded me of dubious assertions about Nathan and Dowling that Lahr had made without any evidence. I asked the fact-checker if this was for an article by Lahr, he demurred. I mentioned that I believed Lahr to be somewhat unethical in his criticism, as he never wrote anything negative about the shows whose stars he’d profiled. I let slip that his bearing was insufferable. At which point the fact-checker groaned, “You don’t have to work for him.” And I swear he whispered something unprintable.