Film Review: Low-Budget Films Were Alive and Well at The Year’s New York Film Festival

By David D’Arcy

A joy ride in Medellin, a right-wing corporate giant scrutinized, and investigative journalist Seymour Hersh on camera

Three independent films got a bounce out of the New York Film Festival and could be coming to you soon.

A scene from Barrio Triste. Photo: NYFF

Barrio Triste by the Colombian-American director Stillz is set in 1980 Medellin, renowned and dreaded as the urban hub of a powerful drug cartel. Its characters are not international narco-dealers, but local teenagers from the hills above the city, opportunistic delinquents on their own turf.

The journey in this urban road movie begins when a local TV reporter prepares to go on the air with a story about some strange, unexplained happenings. The boys, all with shaved heads (“Clockwork Orange 10.0”), steal his camera and his car and drive away to film their own misdeeds. This is literally a bumpy ride, filmed by way of a gritty, shaky aesthetic that evokes — if not quite reproducing — sensurround effects from an earlier Hollywood era. We watch as the boys trash and rob a jewelry store, leaving one dead employee soaking in his own blood. No surprise, they have an excuse—they are not predators but victims, desperate to be loved and respected. That hard luck story is very hard to swallow and its absurdity is compounded by the end of the film. Some otherworldly creatures appear — deus ex machina? Or is it aliens ex machina?

Barrio Triste is more atmosphere than story. The film’s rough look at its adolescent protagonists involves pointing the camera downward much of the time, so we see rutted roads and narrow paths in favelas (“barrios”) where these kids from poor families roam free. Those long shots reminded me of The Blair Witch Project, an earlier walkathon filmed for nothing that looked like it was made for half of nothing. Still, Barrio Triste sustains a consistent look – grey and grim – that sustains a mood of hopelessness, unless you see making a movie in a stolen car with a stolen camera as a sign of hope. Plenty of American filmmakers have felt that way, from Badlands to Thelma and Louise. In this case, the atmospheric barrio context might have been more suited to multiple screens in an art gallery context, not to a linear tale on one screen. Don’t be surprised if you see a future Stillz project at a gallery.

Stillz is best known as a director of music videos and events featuring Bad Bunny and other stars. Exec producer Harmony Korine brought him aboard. IndieWire critic Eric Kohn, who has roots in Colombia, is another producer.

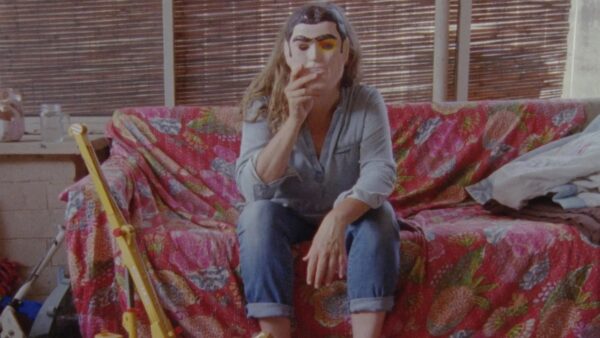

A scene from Lee Ann Schmitt’s Evidence. Photo: NYFF

Lee Anne Schmitt’s Evidence, another no-budget effort, scrutinizes the operations of the Olin Corporation, a U.S. manufacturer of armaments, chlorine, and sodium hydroxide. I say no-budget based on the film’s bare-boned austerity.

Schmitt’s father worked for Olin, traveling all over the world. In the first few minutes of the documentary, we see a series of Japanese dolls that he brought home for her. Elements of Schmitt’s story run parallel to the Olin story.

In a measured voice, which remains constant throughout the film, Schmitt tells us that John M. Olin, the second son of the firm’s founder, took the family’s fortune and dedicated it to the preservation of the system that made its success possible.

That money’s impact, some $370 million, she says, “can be seen on every level of the political landscape.” Her tour of the resulting landscape travels from sites made toxic through pollution to universities and institutions where the company funds programs that have promoted a right-wing agenda for generations – call it ‘poisonous philanthropy’? The firm’s tax-deductible donations are wide-ranging, and Schmitt stresses that dozens of companies invest the same way, to promote ideas that serve them well. So much for higher education’s domination by the left — that universities are now paying millions to expiate.

As Evidence lingers over still images and pans over mute landscapes – some verdant, some skeletal, bereft of nature – we learn that in Wilmington Massachusetts, where Olin made rubber and plastics, it was discovered that contaminants leached into the town’s water. Olin was forced by the government to provide drinking water for the town for over thirty years. Schmitt notes that the chemical giant eventually gave up on cleaning the place. She also adds that Olin’s polluted sites tend to be near communities of African-Americans or Latinos.

The film’s aesthetic is spare. Schmitt’s terse tour through the corruption of Olin-world is unsparing. Her voice makes Dragnet‘s Jack Webb (“Just the facts ma’am”) sound operatic by contrast. The film’s title suggests that there is no need for histrionics — just facts. There aren’t many laughs in the grim evidence she provides, except for the masks that she and her son wear in home scenes – an attempt to depersonalize a deeply personal film? There’s also the ludicrous smugness of the men at meetings of the Federalist Society, the powerful body of right-wing lawyers — funded by Olin and many other corporations — and the blithe gospel of raising kids kids through corporal punishment advocated by Olin beneficiary James Dobson, author of Dare to Discipline, a “spank-for-success” evangelical classic first published in 1971.

In her doc California Company Town (2008), Schmitt took a sober look at early industrial sites. These now-empty places were exploited, then abandoned after minerals, timber, and oil were extracted from the land. “Ghost town” is too gentle a term for what was left: think of areas robbed of their value, often rimmed by breathtaking scenery. In contrast, Evidence presents despoiled landscapes that no one would visit –unless they were ordered to

In today’s atmosphere of threats and fear in higher education, Schmitt’s account of the universities that take cash from Olin makes you wonder. We are told by the Trump administration that academic conservatives are being persecuted? Where would that be? The folks at Olin, the source of so much of the cash dedicated to funding right wing academia, might be praying that Evidence doesn’t find the audience it deserves. Look for it at festivals.

Seymour Hersh in Cover-Up. Photo: NYFF

Evidence might as well have been the title of Cover-Up, the new doc about the investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, still going strong at the age of 88.

Watergate is seen as the triumph of hard-edged reporting over political machinations, with Richard Nixon forced out of office and a star-studded film (featuring Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford) immortalizing his notoriety. But the 1968 massacres at My Lai in Vietnam — that Hersh revealed to the public — were a far greater horror. Only one man ended up being punished (belatedly and briefly) for those murders. We know about My Lai and the guilt of Lieutenant William Calley and many others thanks to Hersh’s dogged journalism, which unearthed the truth about the deaths of hundreds of civilian victims after the US military lied about what happened.

Laura Poitras teamed up with Mark Obenhaus (a former Hersh collaborator) on Cover-Up. Poitras said that it took her 20 years to convince Hersh to cooperate with the filming.

That’s a bit coy. Hersh has been nothing if not a public figure. He’s done endless hours of interviews about his stories and work methods, much of that available online. In Cover-Up, he still mostly avoids talking about his sources. One exception: a young marine whom Hersh visited on a farm in Indiana. Lieutenant Calley had ordered him to kill innocent Vietnamese, and he did. That same young marine had his legs blown off a few weeks after that massacre.

We also learn that Hersh, an AP veteran, reported on My Lai as a freelancer, although dozens of outlets ran the story when he gave it to them. Before My Lai, Hersh reported on atomic tests in the Nevada desert, another dangerous operation with deadly side-effects that the government kept secret

Usually engaging, he sometimes bristles when asked about his reporting methodology. Hersh has his critics. The establishment crowd trashed his book on John F. Kennedy and have attacked his stories about the Nordstream Pipeline bombing. Hersh has still had more than nine lives journalistically. He’s now writing on Substack, more recently about the death of Dick Cheney, for whom he grants no post-mortem reverence.

Cover-Up gets at Hersh’s fierce determination and reminds us that he has always been an odd fit with institutions. There is one aspect of the journalist’s long public life that the doc points to, but misses. When Hersh published a scoop, or a book, it was just the beginning of his campaign to get the word out. He seized the opportunity in interviews to retell whatever news he’d broken or scandal he had exhumed. The result was often a valuable crash course in investigative journalism, akin to a talk about film with director Martin Scorsese. Hersh, a natural storyteller like Scorsese, could turn a question in an interview into a probing hour-long seminar.

The doc, with so much to cover, tells its stories through careful short clips, with nothing approaching such a lecture. Still, Cover-Up is a welcome forum for Hersh, the public journalist. At his advanced age, he’s toned down a bit from the firebrand who once could recapitulate information at breakneck speed. For that, check out earlier interviews on the internet, which are essential for anyone seeking a sense of the man in his prime. As for Hersh today, there’s this film and Substack.

Cover-Up, which also showed at DOC NYC, plays at Film Forum in New York next month before it goes to Netflix.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: "Barrio Triste", "Cover-Up", "Evidence", Laura Poitras, Lee Ann Schmidt, Mark Obenhaus, New York Film Festival, Olin Corporation