Book Review: Writers on the Brink — “February 1933” and the Chilling Parallels to Trump’s America

By Douglas Kennedy

Reading February 1933, just 10 months into Trump’s second mandate, is nothing less than unnerving.

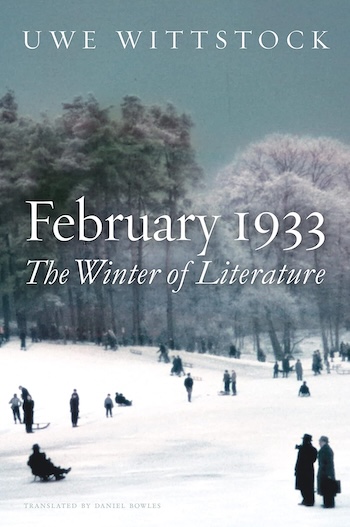

February 1933: The Winter of Literature by Uwe Wittstock. Translated by Daniel Bowles. 288 pages, Polity, $29.95

When considering our current geopolitical state of play — and the fact that there are now two Americas (and we truly hate each other) — I often find myself wondering if its Red versus Blue State origins began with the terrible Domino Theory logic that was held up as a rationale behind our military involvement in Vietnam. As a young adolescent in New York City at the end of the 1960s I remember vividly the construction worker protests against the antiwar movement: “hardhats rightfully beating the shit out of the longhairs” — as my Brooklyn-born, Marine Corps veteran father put it at the time. (Then again, my dad always veered to the hard right side of the street.) This was an era when Nixon’s Silent Majority rhetoric began to cleave the country in two (as brilliantly essayed in Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland) — and when the neoconservative moment began to gain traction.

When considering our current geopolitical state of play — and the fact that there are now two Americas (and we truly hate each other) — I often find myself wondering if its Red versus Blue State origins began with the terrible Domino Theory logic that was held up as a rationale behind our military involvement in Vietnam. As a young adolescent in New York City at the end of the 1960s I remember vividly the construction worker protests against the antiwar movement: “hardhats rightfully beating the shit out of the longhairs” — as my Brooklyn-born, Marine Corps veteran father put it at the time. (Then again, my dad always veered to the hard right side of the street.) This was an era when Nixon’s Silent Majority rhetoric began to cleave the country in two (as brilliantly essayed in Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland) — and when the neoconservative moment began to gain traction.

As such, can we trace the origins of Trumpism back to our Southeast Asian military folly … and the way it began fostering the divisions that are so omnipresent in our national life today?

Similarly, consider the Weimar Republic (1918-1933): a remarkable experiment in Social Democracy and heightened artistic output (which, regarded retrospectively, helped establish modernism in such diverse disciplines as literature, the theater, opera, classical music, and all manner of visual expression). Anyone considering its downfall and the totalitarian era it ushered in might ask some speculative questions:

Was it the 1000% inflation of the Weimar Republic that destabilized the German middle class? Did it make them drawn to a demigod named Adolf Hitler, whose then-nascent National Socialist Party was promising the end of inflation and the creation of a new German Übermensch national identity? Did Hitler’s Manichean rhetoric convince workers and mid-level functionaries (in all professional and public endeavors) to take a chance on a crazed orator who nonetheless seemed to have solutions to pressing quotidian problems? Did that moment in February 1933 — when the Nazis, having only won 40% of the seats in the Reichstag (thereby giving them no majority), nonetheless formed a government (after the elderly president of the republic, Paul von Hindenburg, was schmoozed by Hitler) — was that the moment when authoritarian havoc began? After all, within just a few weeks of gaining parliamentary power Hitler and his Nazis had ended all democratic rule and imposed an autocracy that immediately targeted all artists and writers (especially those without the now de rigueur Aryan DNA).

As the German historian and essayist Uwe Wittstock points out in the prologue to this book February 1933: The Winter of Literature,

“Everything happened in a frenzy. Four weeks and two days elapsed between Hitler’s accession to power and the Emergency Decree for the Protection of People and State, which abrogated all fundamental civil rights. It took only this one month to transform a state under the rule of law into a violent dictatorship without scruples. Killing on a grand scale did not begin until later. But in February ’33 it was decided who would be its target: who would fear for her life and be forced to flee and who would step forward to launch his career in the slipstream of the perpetrators. Never before have so many writers and artists fled their homeland in such a short time. The first exodus of escapees, lasting into mid-March, is also the subject of this story.”

The acclaimed (now largely forgotten) writer Carl Zuckmayer. Photo: WikiMedia

Exodus is, in fact, among the many themes that underscore this riveting narrative. (As well as Wittstock’s other remarkable book, Marseille 1940: The Flight of Literature — to be reviewed at a later date.) February 1933 is indeed about the Winter of Literature, a narrative panorama of what it meant to be a writer in Germany and Austria as Hitler assumed power and all previously held democratic certainties were detonated.

Wittstock is, first and foremost, an accomplished storyteller — and one who has a novelist’s eye for narrative pacing, the intricacies of character, the manifold subtexts lurking behind all interactions, and the fact that, when it comes to essaying the human condition (in all its manifestations) the devil is truly in the details. Consider this account of the friendship between the acclaimed (now largely forgotten) writer Carl Zuckmayer and the World War I fighter ace (turned Nazi) Ernst Udet.

“In 1936 Zuckmayer musters considerable courage and a pinch of recklessness to travel to Berlin from his home outside Salzburg. The Nazis haven’t forgotten how effectively he panned the military in ‘The Merry Vineyard’ and ‘The Captain of Köpenick’ and have long since listed his plays and books on their Index. Still, Zuckmayer cannot be dissuaded and travels anyway to meet actor friends Werner Krauß, Käthe Dorsch, and Ernst Udet, as well. The latter might always label himself an unpolitical person, but three months after the night of the Press Ball, he has joined the NSDAP and launched his career in the Ministry of Aviation under his old squadron commandant Göring. It turns into a somber final encounter in a small, unobtrusive restaurant. The two luxuriate one more time in reminiscences, but then Udet implores his friend to leave the country as soon as possible: ‘Go out into the world and never come back.’ When Zuckmayer questions why he is staying, Udet replies that flying simply means the world to him and talks about the tremendous opportunities as a pilot that his work for the Nazis provides him: ‘It’s too late for me to quit. But one day the devil will come for us all.’ In November 1941 Udet shoots himself in his Berlin apartment. Göring held him responsible for the failures of the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain. Someone has to be the scapegoat. Before Udet kills himself, he writes on the headboard of his bed in red chalk as a rebuke to Göring: ‘Iron One, you have forsaken me!’.”

This excerpt is a perfect example of Wittstock’s intense research. Where did he find that detail about Udet’s final red chalked words? … and the fact that Zuckmayer took his friend’s words seriously: he ended up a farmer in Vermont and had a remarkable postwar writerly resurgence on both sides of the Atlantic.

The great Berlin writer and journalist Joseph Roth. Photo: WikiMedia

February 1933 adopts a wide-screen approach to a moment when it became frantically clear that the new political order in Das Vaterland intended to impose a dictatorship in which writers not toeing the party line were to be proscribed, harassed, and (eventually) imprisoned. As such, the big question facing the cavalcade of personages on show here — from Joseph Roth to Thomas Mann (and his children Klaus and Erica) to Bertolt Brecht to the largely forgotten Kadidja Wedekind (an actress and daughter of Frank Wedekind, who found literary success in 1932 right before the Nazi boom was lowered) — was:

Should I stay or should I go?

Four months after the publication of his masterpiece, The Radetzky March, the great Berlin writer and journalist Joseph Roth wakes on the morning of 30 January 1933 and, in a chapter titled “Hell’s Reigns,” Wittstock delineates the moment when he heads toward the door marked “Exit.”

“Joseph Roth does not intend to wait for the news the day will bring. First thing in the morning he heads to the station and boards a train to Paris. Saying goodbye to Berlin comes easily to him. For years he has worked as a reporter for the Frankfurter Zeitung, and being on the road has become second nature for him. He has been living out of hotels and guesthouses for years. ‘I believe,’ he once claimed boastfully, ‘that I would be unable to write if I had a permanent residence.’”

And then, just as Roth hurries away from the Nazis, a celebrated Czech journalist, Egon Erwin Kisch, arrives in Berlin from China.

“He is a Jew from Prague who, like Rilke and Kafka, belongs to the city’s German-speaking minority. He enjoys making himself the central character of his stories and gives his readers the impression they are standing shoulder to shoulder with him at key venues around the globe. And he possesses great skill in styling himself the epitome of the journalist-as-adventurer and hardcore man: ever in transit to some hotspot or battlefield, ever chain-smoking, ever on the trail of some secret by semi-legal means.”

Again, note Wittstock’s novelistic approach. Kisch was arrested by the Nazis the day after the infamous Reichstag fire (started by Hitler’s supporters — but blamed on leftists), only to eventually be deported from Germany (after doing time in the notorious Spandau prison). February 1933 is brimming with such stories — but what strikes me most forcibly about the book’s quasi-documentary “you are there” approach is the way we are dropped into the center of a crisis where an existential dilemma looms large amidst encroaching fascism: the choice between exile or the near-certainty of persecution if one remains.

The immediacy of this chronicle — its propulsive tempo, the climate of impinging stormtrooper sturm und drang — augments the immensity of the dilemma faced by those writers who knew that to stay was to either enter a Faustian Bargain with Hitler and Co. or face persecution. Whereas to flee meant giving up the creative infrastructure — of theaters, newspapers, literary reviews, publishers, and colleagues — that not only sustained writerly careers but also created (especially in Berlin and Vienna) an atmosphere (prior to 1933) of immense artistic possibility.

German historian and essayist Uwe Wittstock. Photo: Christoph Mukherjee

And Wittstock captures, with chilling deftness, the manner in which the Nazis quickly upended all vestiges of Weimar democracy. A description of a “gargantuan propaganda production” in Berlin — orchestrated by Goebbels (of course) — is particularly telling.

“At Pariser Platz the line of marchers veers to the right down Wilhelmstrasse. The torches cast an uneasy light on the buildings and the people on the curb.… One building farther on, Hitler is standing in an open window of his new official seat. He is illuminated by spotlights from across the street and, surrounded by Rudolf Heß and his ministers Göring and Frick, salutes the crowd below again and again with his raised right arm. At one point, men break loose from their column, form a human ladder, and hand Hitler a rose through his window. Later he has to slip on a brown SA jacket because of the cold, but he is delighted by the hours-long parade review and by Goebbels, who organized it all: ‘Where in the world did he get ahold of so many torches in such a short time?'”

Throughout this exceptional historic chronicle, Wittstock maintains high dramatic tension. And the book doesn’t just deal with the great and the good of Germanic literature of the era. I knew nothing of Vicky Baum, the author of Grand Hotel (“Vicky Baum describes herself as an author in the front row of the second rater”). Or the now-forgotten dramatist Georg Kaiser, the premiere of whose play, Silver Lake, in Leipzig lands him and his creative collaborators in much jeopardy with the new regime.

“Although Kaiser is not Jewish, the Leipziger Tageszeitung refers to him as a “literary Hebrew” and the Altes Theater as a “hotbed of Jewish literati,” and is appalled Kurt Weill was “allowed as a Jew to use a German operatic stage to his sleazy ends.” Eventually, on March 4, brownshirts disrupt the performance with shouting and vulgar behavior until Gustav Brecher, subject to especially brutal attacks for being a Jew, is forced to quit the conductor’s podium and end the show. The artistic directors of all three theaters are dismissed over the following weeks. Georg Kaiser’s literary career is abruptly cut short. Until his death in 1945, no other plays by him will be performed on German stages. Kurt Weill is forced to flee to Paris. Detlef Sierck will leave for the United States with his wife, where he earns acclaim under the name Douglas Sirk as a director of mostly melodramas. Gustav Brecher takes a circuitous route in emigrating to the Netherlands. Fearing the German troops, he along with his wife take their own lives in May 1940.”

Reading February 1933 just 10 months into Trump’s second mandate is nothing less than unnerving. With authoritarian shadows darkening the American homeland, grappling with how previous democratic certainties came unstuck during that crucial moment in that German winter 92 years ago is a sharp reminder that it can indeed happen here.

But, back in the ‘’30s and ’40s, the United States was considered the haven from tyranny. The alarming question today: should a similar sort of fascism (already metastasizing like a virulent cancer) take hold of the United States — with so many other once-centrist democracies swaying to the hard right — where would a targeted writer flee today?

Douglas Kennedy is the author of 27 books, including such acclaimed novels as The Big Picture, The Pursuit of Happiness, and The Woman in the Fifth. He has had a pied à terre in Paris for 25 years. A Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et Lettres, and completely francophone, he is the most regarded of modern American writers in France today. He has also maintained an apartment in Berlin since 2007.