Book Review: Stephen Rebello’s “Criss-Cross”: A Vital Text for Decoding Hitchcock’s “Strangers on a Train”

By Gerald Peary

There’s no question that the author of Criss-Cross approaches Strangers on a Train from a gay-centric viewpoint.

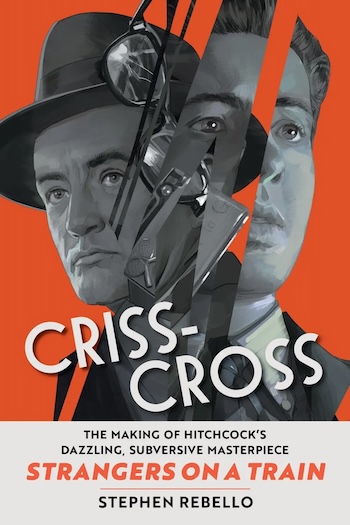

Criss-Cross: The Making of Hitchcock’s Dazzling, Subversive Masterpiece Strangers on a Train by Stephen Rebello. Running Press, 320 pages, $29

Stephen Rebello, the skilled author of Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, comes to Hitchcock’s cinema from an up-front queer perspective. In his newly published Criss-Cross, The Making of Hitchcock’s Dazzling, Subversive Masterpiece Strangers on a Train, he dangles before us a quote attributed to “gay actor/screenwriter Rodney Ackland” (there is no citation) that Hitch told Ackland that if he hadn’t married Alma Reville, “I could have been a poof.”

Rebello concedes that Hitchcock’s words might have been in jest. But there’s no question that the Criss-Cross author detects “poofery” within–Hitchcock’s phrase for his films–“the shadows of concealment,” and maybe nowhere more flagrantly than in 1950 with Strangers on a Train. Could the flamboyant villain, Bruno (Robert Walker), be anything but gay? In a prefatory Author’s Note, Rebello recalls seeing the film while in high school and being taken aback by a scene in which Bruno beckons Guy (Farley Granger) from the darkness “as if he’s inviting him into a seductive covert encounter…as though two attractive adult men might be about to indulge in… a bout of risky public sex.” That heated first viewing of Strangers inspired his tackling this new book. “So, why? Because I had to, Because the movie got under my skin decades ago and has stayed there ever since.”

It’s hard to imagine Hitchcock ever being under the gun. But following the acclaimed Notorious (1946), the box-office failures in a row of The Paradine Case (1947), Rope (1948), Under Capricorn (1949), and Stage Fright (1950), Hitchcock’s status in Hollywood was falling and he was desperate for a hit film. How fortuitous for him to be sent an advance copy of a riveting suspense novel by a first-time writer, Patricia Highsmith. He loved Strangers on a Train, his wife also loved it, so he bought screen rights for Strangers for the very reasonable price of $7,500. And, perfect for Rebello’s thesis about the project, Strangers was authored by someone who in her time would be famously “out,” responsible for, between chilly thrillers, the pioneering 1952 lesbian novel, The Price of Salt.

Much of Strangers on film comes from Highsmith’s book. Guy and Bruno meet for the first time on a train ride and fall into conversation about problematic people who are ruining each of their lives: Guy’s bitchy wife doesn’t want him to divorce so he can marry his true love; Bruno’s bullying powerful dad (read between the lines) is appalled by having an epicene son. Casually, Bruno makes a startling proposal to Guy: I’ll kill your wife, you kill my dad. Nobody will ever know because there’d be no motive connecting us to the murders. Highsmith goes darker than the eventual movie. In the book, nice Guy does exterminate Bruno’s old man. But the movie wisely alters the unpersuasive way Bruno dies in the novel, drowning as Guy tries to save him, and it does away with Highsmith’s clumsy denouement. A drunken Guy confesses aloud that he’s a murderer — and he’s overheard by a detective sitting at the next table. Hardly ever after does one of Highsmith’s criminals get caught.

I once interviewed Highsmith and she denied that her most infamous creation, Tom Ripley, was gay. Oh? If she was asked the question about Bruno, I imagine she’d have given the same evasive answer. Luckily, Hitchcock never inquired of the author, getting his cues straight from the book. According to Rebello, Bruno’s homosexuality was planted in the very detailed forty-five page treatment written by Hitchcock’s long-time friend, playwright-novelist Whitfield Cook. Says Rebello, “As the director anticipated, the purportedly bisexual Cook responded to the novel’s homoereotic undercurrents, perversity, and bleak humor.” Cook made Bruno “a dapper dresser…Bruno’s sartorial flair runs to the flamboyant and garish.” And taking off from Joseph Cotton’s nihilist lady-killer in Shadow of a Doubt,” Cook’s Bruno says things like, “What is a life or two? Some people are better off dead.”

It was Cook who changed Guy from an architect in Highsmith to a tennis pro, and he concocted the classic scene at the tennis tournament in which, following the bouncing ball, everyone’s head in the audience turns right and left except for Bruno, who stares eerily ahead. But it was Hitchcock who intervened about the treatment, ordering Cook to make a drastic alteration from the book. The movie’s Guy will not murder anyone. A Hitchcock cardinal rule is that the audience requires someone to root for. In the film version of Strangers, they would cheer for Guy.

More than in other Hitchcock studies, Rebello argues over many pages how essential Cook was to the final shape of Strangers. Rebello: “It is fascinating, if frustrating, to note how Cook’s importance to the creation of the project has been downplayed, when not ignored entirely. It would be heartbreaking and infuriating if Cook’s sexuality were part of the reason for his relative anonymity.” (Cook does get an adaptation credit on the release film. I don’t know why that doesn’t placate Rebello.)

Farley Granger and Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train.

After Cook left the film project, Hitchcock went through a group of screenwriters, each putting his/her mark on various iterations of a Strangers script. Among them was Raymond Chandler, who was brought in because he was a prestige literary name. He is called a “homophobe” by Rebello and got along as badly working alongside Hitchcock as he’d done collaborating with Billy Wilder on Double Indemnity. Chandler was fired at some point by Hitchcock, but Warner Brothers insisted that Chandler be the main credited screenwriter because of his mystery-writer fame. Because two writers were hired after Chandler left, it’s very hard to surmise what remains of his work in the final version. He did contribute the scene where Guy seems to be going to murder Bruno’s father at home, but actually is planning to warn the dad about having a psychotic son. It was Hitchcock himself who added a neat surprise to this scene — and made it explicitly homoerotic. When Guy ventures into a bedroom, it’s Bruno under the covers waiting to see him.

Hitchcock wanted Montgomery Clift to play Bruno, but Clift turned him down. Rebello speculates it was because Clift didn’t want to reveal his queerness. And this is wild: young Marlon Brando was considered for the role! Brando as Bruno! Instead, he opted to be Stanley in the movie version of A Streetcar Named Desire. As for Guy, the filmmaker hoped for a star like William Holden with whom the fans could empathize. But Jack Warner, head of Warner Brothers, was in a niggardly mood when considering Stranger’s budget. So Hitchcock had to settle for two less costly actors. Not that he finally objected. He liked working with Farley Granger on Rope so he was fairly okay having Granger as Guy. As for Robert Walker, he must have sensed he could tap into the dissatisfied, combustible personality hidden behind the actor’s affable romantic comedy roles. After being dumped by his wife, Jennifer Jones, a despairing Walker had bouts with alcoholism, fights with police, and time spent in the psychiatric ward at the Menninger Clinic. Hitch saw correctly that the actor’s estrangements could translate to a marvelously devious Bruno.

Because of Granger’s frank autobiography, today we know the real criss-cross. Granger played the straight Guy, but he was gay in real life, or marginally bisexual. (He slept with both Leonard Bernstein and Shelley Winters.) Walker, who portrayed the gay Bruno, was decidedly straight. But he told Granger he intended to play Bruno as homosexual. Says Rebello approvingly of Walker’s deliciously swishy performance, “By turns charming, dashing, awkward, vulnerable, chilling, barely suppressing rage, stalker-like, he bats his lashes and looks Granger up and down in about as queer-coded way as a Hollywood leading man could get away with on the screen in the 1950s.”

How Walker decided to do Bruno was A-OK with Hitchcock, who got on brilliantly with his two leads. Granger later said that Strangers was his happiest filmmaking experience. For a now-famous scene, Walker spent four obedient hours being photographed reaching through a storm drain for a dropped cigarette lighter. He later said of his demanding director, “If that’s being a taskmaster, I’ll happily work with such a taskmaster on every picture from here on in.” Rebello notes that Hitchcock personally chose the debris at the bottom of the storm drain: “an orange peel, a chewing-gum wrapper, wet leaves, and crumpled bits of paper.” As with every film he made, Hitchcock was control-freak prepared on Strangers, beginning with the drawings he brought to the set each day illustrating every upcoming shot.

The biggest Strangers catastrophe occurred after filming had ended. The tragic death of Walker at age 32, after a doctor wrongly treated him with sodium amytal. But Strangers was a smooth shoot. The challenges that arose were formidable technical ones, like how to film the climactic fight on a merry-go-round, rather than with the cast and crew. The only exception was Hitchcock’s tense relationship with Ruth Roman, the actress playing Guy’s society lady fiancé. She was foisted on the film by an adoring Jack Warner when Hitch wanted a very young Grace Kelly.

Leo G. Carroll, Ruth Roman, and Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train.

As Rebello explains, Roman was a proudly working-class girl from Lynn, Massachusetts, and Hitchcock could not make her into the Washington Brahmin demanded for the part. At one point, he threatened that she could say her lines whatever way and he would dub her in post-production. Apparently, Roman was gutsy enough not to be intimidated by her bullying director. And she was backed all the way by Warner, who insisted that the last scene of the movie—a silly one with she and Granger on a train on their honeymoon—be there because the audience “couldn’t get enough of Ruth Roman.” (It had been shot by Hitchcock only to appease his strong-armed studio employer, hoping it would not survive.)

It would be a few years, the mid-1950s, before the French film critics at Cahiers du Cinema would discover the Christian existential themes in Hitchcock’s oeuvre. At its 1950 release, Strangers got decent reviews, but it was judged to be nothing deeper than well-done entertainment, a good thriller. Only one critic noticed in his review that Bruno was gay and that was The Nation’s Manny Farber, who pointed to “the travestied homosexuality of the murderer.” The box office was far better than that of other recent Hitchcock films. Yet, according to The Motion Picture Herald, it was not quite up to the proceeds of Ma & Pa Kettle Back on the Farm or Bob Hope’s The Lemon Drop Kid.

Seemingly, Hitchcock’s deft helming of Strangers didn’t quite win over Jack Warner. In 1953, his studio in financial decline, he demanded Hitch take a 90% salary cut. This humiliation for the filmmaker ended in triumph. Hitchcock went over to Paramount Pictures, where he would happily make Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Trouble with Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Vertigo, and Psycho.

I am glad that Rebello acknowledged my name when he quoted the interview I did with Highsmith. But a serious problem with Criss-Cross is that the publisher did not insist on supplying footnotes and/or citations. It’s impossible to unravel what significant things Rebello discovered about Hitchcock and Strangers (I am certain there are many) and what he drew from other sources, such as respected director biographies by Donald Spoto and Patrick McGilligan. I would especially like to know how much he is indebted to Bill Krohn’s Hitchcock at Work (2003) and to David Greven’s Intimate Violence: Hitchcock, Sex, and Queer Theory (2017).

Gerald Peary is a professor emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His last documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, played at film festivals around the world, and is available for free on YouTube. His 2024 book Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, was published by the University Press of Kentucky. His newest book, A Reluctant Film Critic, a combined memoir and career interview, can be purchased here. With Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Tagged: "Strangers on a Train", Alfred-Hitchcock, Farley Granger, Patricia Highsmith, Robert Walker

A fine review, Gerry– sparks deep interest. Walker was a distraught soul. Knowing this makes his breezy, charming early screen persona seem like an acting triumph. Proof that he was headed for greater things before the incompetent doctor murdered him is his performance in My Son John. If one looks at that film’s red-baiting as a metaphor for American anti-intellectualism, there’s a lot more going on there than anti-Communism. (Despite Leo McCarey).