Book Review: “Pre-Code Essentials” — When Moviemakers Played the Game of Evade-The-Censor

By Betsy Sherman

Film fans who love the style and spirit of thirties Hollywood will have to control themselves from drooling happily all over this fabulously written, photo-filled volume.

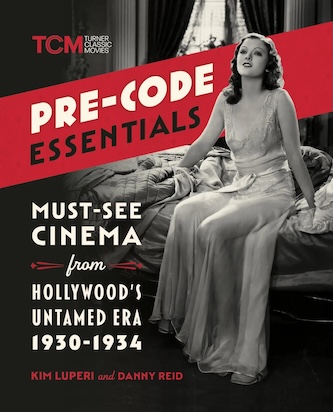

Pre-Code Essentials: Must-See Cinema from Hollywood’s Untamed Era, 1930-1934 by Kim Luperi & Danny Reid. Running Press, NY., 256 pages, $ 13.99

From the early days of cinema, there have been groups decrying a corrupting effect of the seventh art on the morals of its viewers. In the U.S., decisive action was taken in July of 1934 that divided Hollywood output into a “before” and “after.” As of that month, and stretching over more than three decades, movies had to earn a seal of approval from the Production Code Administration (PCA)—also known as the Hays Office—a group that had its roots in the movie business’s effort to police itself during the ’20s.

The Motion Picture Production Code, which had been introduced in 1930 but much flouted, began to be consistently enforced after that date. A fellow teeth-baring watchdog, the Catholic Legion of Decency, also came into being in 1934. It had the clout to keep picturegoers away from the movies the organization denounced—the penalty being the closure of the gates of heaven to anyone who had partaken, I guess. The dividing date created the categories of pre-Code-enforcement and post-Code-enforcement, which are easier to just call pre-Code and post-Code.

Fabulously written and designed, Pre-Code Essentials: Must-See Cinema from Hollywood’s Untamed Era, 1930-1934 is by Kim Luperi and Danny Reid. The latter founded the invaluable website pre-code.com and the volume bears the Turner Classic Movies imprint. Film fans who love the style and spirit of early-thirties Hollywood will have to control themselves from drooling happily all over the photo-filled volume (the trade paperback, that is—it’s also offered as an e-book and audiobook). It can serve as an enticing entryway for those new to that frisky period when moviemakers played the game of evade-the-censor.

The authors describe the 1930 Code—a version of which can be viewed here and in an appendix—as “a guiding document created as a philosophical treatise to rationalize film censorship.”

Reid and Luperi’s challenge was to choose 50 pre-Codes to celebrate and examine (a torturous task, to pick only 50!). Each movie’s section includes a review plus background information, and, in many cases, primary documents related to its censorship standing. There’s a glossary and cast of “characters” explaining groups like the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), its Studio Relations Committee (SRC), its Production Code Administration (PCA), and individuals such as former postmaster Will H. Hays (head of the MPPDA), Joseph Breen (from 1934-1954 the head of the PCA) and Colonel Jason Joy (head of the SRC until 1932).

The beloved TCM has introduced TV watchers to thousands of pre-Codes, down to the most obscure. The dominant impression from pre-Code marketing in recent decades (DVD boxed sets, for example) is that pre-Code’s attraction is about sex, adultery, and the showing of female flesh (with bits covered strategically by shiny lingerie). But it isn’t all about whether Betty Boop’s hemline landed above (pre-Code) or below (post-Code) her garter. During these years, which coincided with the worst of the Depression, films occasionally questioned political, social, economic, and gender norms. There were doubts expressed about religion, the sanctity of marriage, the nuclear family, and whether the American Dream was still possible. There was cynicism and a looser attitude towards crime (perhaps borne of copious drinking during Prohibition). All these nuances are covered in the book’s scrutiny of the period’s emblematic films.

Pre-Code Essentials is “Dedicated to Barbara Stanwyck and all the other dazzling, daring, no-nonsense dames of the world.” Be sure to check out the actress’s 1933 Baby Face, a storied pre-Code on which author Luperi wrote her thesis—but look for the restored version.

Barbara Stanwyck and Theresa Harris in 1933’s Baby Face.

On to the chosen movies (“the most representative and notable films of the early 1930s”). They’re presented in chronological order of release. While you can skip back and forth and use the volume as a reference, I recommend reading it cover to cover for a clear understanding of the timeline of this dramatic span of Hollywood and American history.

The Divorcee (released April 1930) is a splendid place to start. It’s the sassy drama that launched Reid’s pre-Code habit. Norma Shearer spearheads this last hurrah for the ’20s Jazz Age. Her husband, M-G-M mogul Irving Thalberg, didn’t think she could pull off the steamy role of a woman who turns the tables on her adulterous husband, later ex-, by dabbling in casual sex. Shearer pulls it off in spades. We see a letter in which SRC head Jason S. Joy bemoans a “cycle of sophistication” (another word for permissiveness). The authors salute the film as “a pivotal nod to women’s autonomy that’s just as timely a century later.”

The last film of the 50 is Murder at the Vanities (May 1934). By the time of its release, the fearsome Joseph Breen had taken over as head of the PCA. This musical, which included suspense elements, exploded censors’ heads with its number “Sweet Marijuana”. The offensive scene was suppressed at the time, but it may not have been cut from the original negative as promised by Paramount in a letter printed in the book. Luckily, it was restored, and became midnight movie fare in the ‘70s.

Kay Johnson vamping it up in 1930’s Madam Satan.

In between, the authors discuss the U.S.’s messy, decentralized censorship apparatus. A movie deemed problematic would be cut differently in different states and localities. One interesting example is Cecil B. DeMille’s racy Madam Satan (Sept. 1930), much of which is set at a spectacular masquerade ball held on a zeppelin. The title is the nom de guerre of a woman who’s using her masked character to win back her husband from his wild-thing girlfriend, Trixie (Lillian Roth). Some censor boards interpreted Madam Satan as a farce and hardly touched it. Chicago’s requested the removal of a quip that a man aims at Trixie: “I know you by your appendix scar.” Massachusetts threw out the scene where Trixie parachutes into a Turkish bath, along with her declaration: “Is a body made out of flesh and blood—is that what you mean? Well, I’m not ashamed of it—it got me where I am today.” By the way, Massachusetts restricted some movies so they couldn’t be viewed at all on Sundays.

Another target of the censor boards was the romanticizing of crime. The off-screen story of gangster classic Scarface (Aug. 1932), starring Paul Muni, is as tumultuous as the on-screen action. This cross between Al Capone and the decadent Borgia family is like an opera with machine guns. The battle to get it made, and keep it intact, was waged by two strong-willed men, director Howard Hawks and producer Howard Hughes. The authors write, “Hawks’s fusion of savagery and humor sets the picture apart from other pre-Code gangster entries.” They print a memo directing editors what to cut, so the film can be passed by the Pennsylvania censors. The movie pushed the envelope with its amoral attitude, stark violence, and the implication of incest between protagonist Tony and his sister. The controversy had a long life: Hughes pulled Scarface from circulation in 1947 and it wasn’t revived until 1979.

Warner Bros. was the studio most inclined to tackle political and social issues. The section on Heroes for Sale (June 1933) calls it “one of the most arresting and immediate documents of the Depression.” The protagonist, played by Richard Barthelmess, is a wounded World War I veteran who becomes dependent on morphine. At times, he experiences homelessness, unemployment, imprisonment, and police brutality. Still, it ends on an optimistic note with quotes from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s inaugural address (delivered in March 1933). Further relevant fare from Warners includes I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (Nov. 1932) and Wild Boys of the Road (Oct. 1933). Even the “Forgotten Man” number in Gold Diggers of 1933, staged by Busby Berkeley, identified a problem and saluted FDR’s solution, the National Recovery Act.

Richard Barthelmess, Aline MacMahon, and Loretta Young in a scene from 1933’s Heroes for Sale.

M-G-M released the uncategorizable, batty Gabriel Over the White House (March 1933), in which said angel transforms an ineffectual president (Walter Huston) of a crumbling U.S.A. into a fascistic autocrat who uses drastic means (such as dissolving Congress) to achieve his goals. This is shown to be a good thing! The authors posit, “Power didn’t necessarily corrupt in this movie, but it’s a reminder of just how much it can in the wrong hands—and that’s a message that still resounds incredibly loudly.”

The horror movie evolved during the early ‘30s. The best-known titles covered are Universal’s Frankenstein (Nov. 1931) and RKO’s King Kong (Apr. 1933). That the morality overseers would try to protect viewers from terror is understandable; they also took issue with Dr. F’s penchant for comparing himself to God. The authors enthuse over the technical innovations of Paramount’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Dec. 1931), starring Fredric March, and recount the perversions in Universal’s The Black Cat (Mar. 1934), directed by Edgar G. Ulmer.

Finally, the authors present the pre-Code era as one in which difference was more acceptable onscreen. There was stereotyping, yes, but minority ethnic and racial groups were more visible than post-1934. The write-up for Safe in Hell (Aug. 1931) includes a sidebar devoted to African-American supporting players Nina Mae McKinney and Clarence Muse. The Shanghai Express (Feb. 1932) section stresses the prominence of Anna May Wong.

Aline MacMahon and Ann Dvorak in 1934’s Heat Lightning.

Feminism can be in the eye of the beholder: sometimes women in non-traditional roles and garb is a win, such as Aline MacMahon in overalls running a gas station and restaurant with sister Ann Dvorak in Heat Lightning (Mar. 1934). Queer content came out of the closet when Greta Garbo, as 17th-century Sweden’s Queen Christina (Dec. 1933), kissed a lady-in-waiting and embarked on a love affair with John Gilbert while disguised as a man (predictably, there was a censorship battle).

Luperi and Reid handled their mission with affection, humor, and a frankness that does justice to the topic (I appreciated how they call a rape a rape, without using euphemisms). They did an abundance of archival research to dig deeply into each choice. Thanks to film preservation, it’s easier than ever to watch uncensored pre-Code films. Now there’s a swellegant companion for our binges.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.