Film Review: “Sentimental Value” — The Art of Family Strife

By Peg Aloi

Director Joachim Trier is a masterful arbiter of storytelling conceits and tones: by turns subtle, ironic, melodramatic, cold, and, often, heartbreaking.

Sentimental Value, directed by Joachim Trier. Screening at AMC Boston Common, Landmark Kendall Square Cinema, Coolidge Corner Theatre

Renate Reinsve in a scene from Sentimental Value. Photo: NEON

An empty house, surrounded by trees, is being spoken about by a woman who may have lived there. She recalls how, as a child, she thought that the house was alive, wondering if it had feelings, if it enjoyed being filled with people, light, and noise. The opening scene of Sentimental Value establishes an elegiac, melancholy tone. Cut to: the opening night of an Anton Chekhov play. Things aren’t going well. Nora (Renata Reinsve) is shown preparing to go on stage in a voluminous black silk gown. She is suddenly overcome with extreme panic and anxiety.

There’s a suggestion that this is a major production, helmed by a well-known stage actress. The stage manager, director, and other crew members appear to recognize this behavior, as if they’ve dealt with it before. Still, the atmosphere is chaotic, as if anything might happen. Nora finds fellow actor Jakob (Anders Danielsen Lie, seen in Trier’s Oslo, August 31st and The Worst Person in the World) backstage and tries to initiate a quick sexual encounter, presumably to calm her nerves. He is briefly tempted, but refuses. We later find out the two have been having a clandestine affair. Eventually, Nora manages to pull herself together, and the film cuts to a standing ovation and the sight of her smiling, triumphant face. It gradually becomes clear that Nora, despite her success, lives her life in a way that courts disaster and sabotage, struggling with emotional stability.

Nora’s sister Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) has a lovely family with two children and a calm, devoted husband, and works as a therapist. The two sisters go to their childhood home to clear things out after the death of their mother. At the funeral, their father shows up, surprising them both. Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård) is cordial, even affectionate, with his daughters, but they’re noticeably guarded, especially Nora, who never forgave him for walking out on the family decades ago. Gustav is a filmmaker who enjoyed a high-profile early career; at this point, he is planning a comeback with a new project after a fallow period. He asks Nora to read the screenplay (which is apparently loosely autobiographical) and consider playing the lead role.

It’s a signature narcissistic move by a man who abandoned his family. He knows such a role would be a significant career move for Nora while also making it appear they’ve reconciled after years of estrangement. Nora argues with her father, accusing him of being insensitive and manipulative, and refuses to participate. Soon after, at a film festival where Gustav’s work is being showcased, we learn that his first film starred his daughter Agnes when she was a child. After seeing this movie, popular American actress Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning, in a brilliantly nuanced performance) fangirls over Gustav, takes selfies with him for Instagram, and invites him to dine with her entourage. Gustav asks if Kemp would like to play the lead in his new film. She is flattered, asks to read the script, and accepts — more evidence of Gustav’s selfishness and underlying cruelty, of which he seems blissfully unaware.

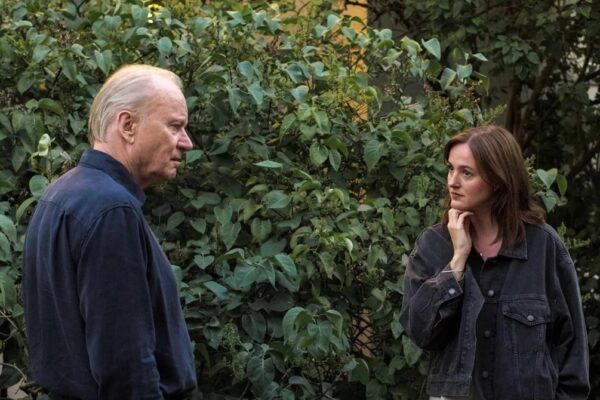

Stellan Skarsgård and Renate Reinsve in a scene from Sentimental Value. Photo: NEON

We learn that, after Gustav’s debut won accolades for both him and his daughter, Agnes never acted again, while Nora pursued performing from a young age. It’s a classic psychological setup, complete with doubling and barely concealed resentment, with shades of Chekhov, Ingmar Bergman, and Arthur Miller. This complex and volatile family dynamic feels poised to reignite after a long dormancy. Nora’s traumatic childhood experiences remain a formidable obstacle in her life. Gustav heaps more kindling on the psychic fire by announcing he will film on location at the family house and invites Kemp to Norway to shoot scenes there. Meanwhile, Agnes digs into the family history to learn more about her grandmother, who inspired the lead character. Nora is shocked to discover that her grandmother’s mental health struggles were not unlike her own.

Despite their tense relationship, there’s an uncanny similarity in the facial expressions, mannerisms, and personality traits of Gustav and Nora — feats of stunning acting prowess by Skarsgård and Reinsve. This sparks speculation: how might their lives have been different had they been a functional family and stayed in touch over the years? Agnes also seems to understand that her life would have turned out differently if she had chosen to continue acting. She’s acutely aware of her relative stability compared to Nora and accepts her role as her sister’s patient confidant and, sometimes, caregiver. It’s a somewhat thankless responsibility, and the character role might have been similarly rote, but Lilleaas’s performance is understated and calmly luminous. Nora’s chosen career path, despite its anxiety-inducing pressure, suggests she has a deep need for attention or approval — a fairly common trajectory shaped by childhood trauma and insufficient parenting (enter attachment disorder conversation).

It’s all too easy to psychologically analyze these characters, prejudging their actions and motivations, even though the film seems to demand that we do so at times. Director Joachim Trier is a masterful arbiter of storytelling conceits and tones: by turns subtle, ironic, melodramatic, cold, and, often, heartbreaking. Sentimental Value unfolds deftly through encounters between the characters, a journey whose way stations are often revelatory and unexpected. Fanning proves particularly adept at conveying her character’s subtle decision-making and all-in approach to acting. Rachel works hard to connect with the role but finally realizes that she may not be right for it. Nora’s realization that Gustav’s script could just as easily be about her as about her grandmother causes her to reconsider, and some form of détente appears on the horizon. The film’s final scenes are wordless, emotionally detailed, and breathtaking. It’s tempting to assign some significant message here: a hymn to art’s transformative power, its ultimate importance for some, its function as a refuge from life’s difficulties. But none of that matters when we see, hear, and feel the heart-shattering epiphany at the film’s end — a moment that brings past and present, life and art, full circle.

Peg Aloi is a former film critic for the Boston Phoenix and member of the Boston Society of Film Critics, the Critics Choice Awards, and the Alliance for Women Film Journalists. She taught film studies in Boston for over a decade. She has written on film, TV, and culture for web publications like Time, Vice, Polygon, Bustle, Dread Central, Mic, Orlando Weekly, Refinery29, and Bloody Disgusting. Her blog “The Witching Hour” can be found on substack.

Tagged: "Sentimental Value", Elle Fanning, Inga Ibsdotter Lillieaas, Joachim Trier, Renate Reinsve