DocTalk: Wicked Queer Festival — Make Your Body Talk

By Peter Keough

The word made flesh at WQ: Docs

WQ: Docs. November 14-17 at the Brattle Theatre, Cambridge

Once again, the Wicked Queer Festival not only presents documentaries that explore the meaning of gender, sexuality, and identity, but also expand the conventions of nonfiction film. Here are two examples of works that focus on individuals who put their bodies and lives on the line to maintain their identity, desires, and ideals.

Brigitte Baptiste in Brigitte’s Planet B. Photo: Wicked Queer Festival

Brigitte Baptiste, the Colombian transgender ecologist who is the subject of Santiago Posada’s polymorphous, playful, and inspiring Brigitte’s Planet B (2025; November 15 at 2:30 p.m.), has said that “nothing is queerer than nature.” By that, she means that the constantly evolving panoply of life does not respect such rigid binary divisions as male and female, or nature and culture for that matter. If we are to survive as a species, then neither should we.

Posada elucidates Baptiste’s ideas and work in a career that has included serving as the director of Colombia’s Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Research on Biological Resources and of the Universidad EAN. It follows her as she appears on talk shows and travels to conferences. But it is also an intimate profile, chronicling her personal odyssey, which took a major turn in the ’90s when she decided to become a woman, taking as her new first name that of the actor and animal rights activist Brigitte Bardot. Adriana Vásquez, her wife and mother of her two children, understandably found this to be a challenging adjustment (she still calls her Luis). But they remained a couple and, with their daughters, make up the kind of evolved family unit that offers hope for our difficult times.

Posada intercuts these candid observational sequences and archival footage with disorienting imagery of sprouting mushrooms, colorful animal mating behavior, and swarming sea and avian life. The imagery astonishes and delights. It is sometimes optically altered and resembles melting, kaleidoscopic mandalas or AI-enhanced lava lamps. Baptiste herself mirrors this protean display of the biosphere by way of her elaborate, ever-changing wardrobe. A key element in the film and in Baptiste’s philosophy is irony and humor, which is established in Brigitte’s Planet B’s opening sequence, as she and her children are taking a quiz in which they are asked to define the word “nature,” with Baptiste suggesting that such definitions are what got us into this fix in the first place.

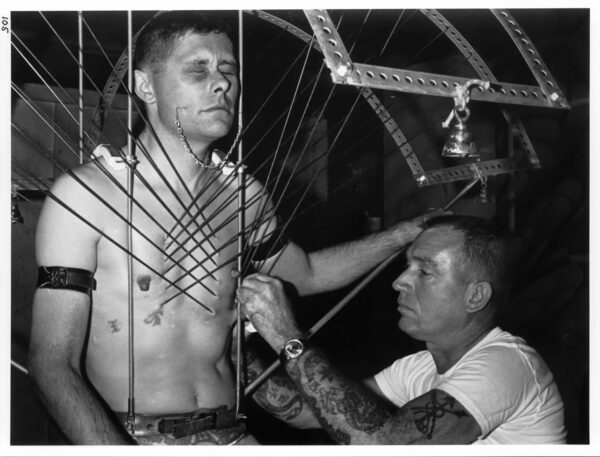

Archival photograph in the documentary A Body to Live In. Photo: Wicked Queer Festival

Fakir Musafar, subject of Angelo Madsen’s alternately startling and trancelike A Body to Live In (2025; screens November 15 at 8:30 p.m.), started life as Roland Loomis in 1930 in Aberdeen, South Dakota, on former Sioux tribal lands, an influence in his work that would later expose him to accusations of cultural appropriation. He was, in his own words “puny and effeminate,” with no friends and a fascination for the weird and arcane, like carnival freak shows, magic tricks, vaudeville acts, and images of exotic cultures in National Geographic. Though his strict Lutheran mother had hoped he might grow up to become a minister, he would seek transcendence in other, less orthodox ways, as demonstrated by the photographs at the beginning of the film of him at 14 with a rope coiled around his neck and a belt compressing his waist to Scarlett O’Hara dimensions.

The young Loomis was given a camera and asked his mother to use the fruit cellar (shades of Psycho) as a darkroom. There he would photograph himself in acts of self-bondage, with rows of clothespins attached to his flesh, lying on a bed of nails, or performing body piercings. When he was 17, his parents gone for a while, he took advantage of their absence to starve himself and chain his naked body for days to the cellar wall until he underwent a visionary experience. He led a secret life of transgressive ecstasy, but in South Dakota he had no one to share it with.

That changed when he moved to San Francisco and found a few like-minded people who would help him undertake his more elaborate endeavors. Among his new acquaintances were Anton LaVey, an organist who played in bars and would later found the Church of Satan (“We really hit it off,” he recalls) and a ventriloquist (“a real weirdo”) with whom he put on shows and had wild parties.

But it was his encounter with fellow piercing aficionados Doug Malloy and Jim Ward in the ’70s that encouraged Loomis to drop his straight persona, change his name to Fakir Musafar (taken from that of a 12th-century Sufi mystic), share his esoteric know-how, and show off in public his by then formidable array of piercings, tattoos, and other body art. Together they started the magazine Piercing Fans International Quarterly in 1977, appeared in the 1985 documentary Dances Sacred and Profane, and were featured in V. Vales and Andrea Juno’s book Modern Primitives in 1989. But it was Musafar who became an icon. No longer locked up in his family fruit cellar, he was an underground celebrity, a ubiquitous talk show guest, with his once taboo photos featured in the book Spirit + Flesh (2002) and shown in galleries.

Musafar gave hundreds of interviews, his last taking place on his deathbed (he died in 2018 at 88), many of which — especially the last — Madsen draws on in his film. He also interviews other significant people in Musafar’s life, especially his wife and performance partner Cléo Dubois. These interviews are intermixed in a nonchronological, collage-like structure, with images backed by disembodied voices and an incantatory soundtrack evocative of a Kenneth Anger film.

A Body to Live In recalls other documentaries about artists and visionaries driven to physical extremes, from Kirby Dick’s Sick: The Life and Death of Bob Flanagan, Supermasochist (1997) to David Charles Rodrigues’s S/He Is Still Her/e: The Official Genesis P-Orridge Documentary (2024). Though Musafar did not specifically identify as gay, queer, or transgender, he seemed driven to transcend the limitations of gender and the flesh by transforming the body itself.

Another Arts Fuse view of A Body to Live In.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, including Kathryn Bigelow: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2013) and For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: "A Body To Live In", "Brigitte’s Planet B", Angelo Madsen, Brigitte Baptiste, Santiago Posada