Book Review: Canceling Equality — Julia Ioffe’s Personal and Political History of Russian Women

By Clea Simon

This heartbreaking book documents the history of contemporary Russia through its women, a perspective that highlights its dramatic and devastating slide from an idealistic egalitarian state into a repressive and sexist nation that leans heavily on fascist ideology.

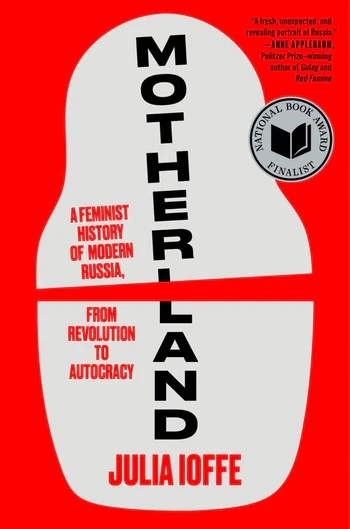

Motherland: A Feminist History of Modern Russia, from Revolution to Autocracy by Julia Ioffe. Ecco, 512 pp., $35

For Julia Ioffe, the personal is political. In her heartbreaking new book, Motherland, the political reporter (and Russian émigré) documents the history of contemporary Russia through its women, a perspective that highlights its dramatic and devastating slide from an idealistic egalitarian state into a repressive and sexist nation that leans heavily on fascist ideology.

For Julia Ioffe, the personal is political. In her heartbreaking new book, Motherland, the political reporter (and Russian émigré) documents the history of contemporary Russia through its women, a perspective that highlights its dramatic and devastating slide from an idealistic egalitarian state into a repressive and sexist nation that leans heavily on fascist ideology.

To do this, Ioffe takes a novelistic approach, juxtaposing brief profiles with historical milestones — including many that have customarily been seen from a male point of view. As she opens her history, the author presents the Russian stereotype, a woman who “could stop a galloping steed or enter a burning building if that was what their families and their country required,” and, rather than dispute this cliché, holds it up to the light to reveal not only what such women could but what, at one point, did accomplish.

Starting with the multiple revolutions of 1917 that created the Soviet state and moving up through the war on Ukraine, she highlights such thinkers, instigators, and heroines as Alexandra Kollontai, named in 1917 the first Soviet commissar for social welfare. Among them, Ioffe weaves her own foremothers, starting with her great-grandmother Rivka (Riva) Weisser, a Ukrainian Jew who in 1921 took advantage of the new freedoms granted to Jews by the Bolsheviks to leave her Pale of Settlement shtetl (fleeing pogroms that had killed her mother) to study in Odessa and Moscow.

In addition to tying her own history in with that of the country of her birth, Ioffe uses her foremother as an example of the great leaps being made — and great work being done — by women. Weisser, for example, volunteered as an adult literacy teacher with the Zhenotdel, the Women’s Section of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and a Kollontai brainchild, with long-lasting repercussions.

“When the Bolsheviks took over, out of the 17 million illiterate people in the Russian Empire, 14 million were women,” writes Ioffe in one of her succinct, and highly readable, data dumps. By 1926, 42 percent of Russian women could read; by 1939, more than 80 percent. “By the time my mother went to university in 1976,” she concludes, “virtually all women in the Soviet Union could read, the highest literacy rate in the world.”

Ioffe’s use of such profiles as Weisser and Kollontai gives faces to the numbers she lays out, the overall effect being both accessible and also intimate. And this is an intimate history: As much a social as political recounting, Motherland focuses on such issues as birth control, sexual mores, and marital law. These, Ioffe makes clear, are more than domestic issues. Although the male leaders of the Revolution, including Lenin, were “deeply ambivalent about birth control and family planning,” such issues would be key to building a new republic. As Inessa Armand, another of Ioffe’s profile subjects, wrote in 1919: “Until the old forms of life, education, and child-rearing are abolished, it is impossible to obliterate exploitation and enslavement, it is impossible to create the new person, impossible to build socialism.”

Thanks in large part to such early party powers as Kollontai, the constitution of 1919 guaranteed free maternity and child care, the legalization of abortion, the removal of all gender restrictions on education and employment, and the relaxation of divorce laws, “all part of a plan in which every citizen was required to work and receive the same minimum wage.”

These freedoms, Ioffe explains, created an empowered citizenry and a template for generations. For example, Ioffe’s sister, an oncologist, is the fourth generation of women in their family to practice medicine (two of their great-grandmothers were doctors). Such women were also crucial in building the martial strength of the new state: Nearly one million women fought in the Red Army in World War II, including such noted figures as sniper Lyudmila Pavlichenko and fighter pilot Marina Raskova.

But the egalitarian dream was short-lived, and the backlash against such women was relentless as male leaders, despite the law, sought to preserve the power and rights of traditional roles. Before the war had ended, Stalin had resegregated schools by gender; individual women were targeted, some combatants denigrated as promiscuous while others were simply sidelined. Despite her record, Pavlichenko, for example, was not allowed back into combat following a state-sponsored propaganda tour of the United States. Worse was to come.

Political reporter (and Russian émigré) Julia Ioffe. Photo: Max Avdeev

Ioffe illustrates the shift in her profiles. When Stalin, 38, married the teenage Nadzhda Alliluyeva, he wasn’t looking for the kind of partner or equal that Lenin arguably found in Nadezhda Krupskaya, his wife (who was better educated than her husband), or Armand, Lenin’s lover, relationships that have long overshadowed their very real contributions. As the author traces the sad decline of the ideal of the strong Soviet woman, Alliluyeva’s suicide, in 1932, leads to the long tragedy of her daughter, Svetlana. Other profiles include the women raped by Lavrenty Beria, the chief of Stalin’s secret police, and those condemned in Stalin’s purges because of the weakest of connections to so-called traitors. Under Khrushchev, Brezhnev, and Andropov, the segregation deepens, and, despite Gorbachev’s attempted reforms, the die is cast.

This reactionary pushback reaches a head in Putin’s Russia. The author voices her deepest distress when she begins recounting her return to the country she had left in 1990, as a seven-year-old. The year is 2009, and Ioffe, on a Fulbright scholarship, arrives expecting “to find a city full of women I recognized.” Instead, she discovers a world where old-school sexism rules, where women, hoping to snare rich husbands, attend classes at new institutions like the Life Academy, where they are taught tricks of flirtation and fellatio.

The regression runs deep: Nazi concepts, such as the idealization of the “hero mother” who has at least 10 children, have become enshrined in a newly conservative society, where “bearers of traditional values” are celebrated. The Orthodox Church has been reinstated as a full partner of the government, and Putin has squelched a popular attempt at recriminalizing domestic violence (personified in the story of the remarkably resilient Margarita Gracheva, whose hands were cut off by her jealous husband).

Although Ioffe drills down on factual detail, with extensive footnotes on her sources, this last segment of the book is its most personal. In it, Ioffe refers to her own relationship troubles, showcasing how she has internalized the contemporary Russian perspective even as she wrestles with a boyfriend who tells her, “You don’t know what you want… I do.” It’s unsettling after the cool-eyed history, and yet it gives body to the dilemma of the contemporary Russian woman, especially one who has just turned 30.

Rather than blaming the victims, however, she turns her attention to Russian men, exploring the historical bases for their misogyny, from unemployment to the rampant alcoholism that has drastically lowered the Russian male lifespan. Examining the rise and punishment of Pussy Riot and Yulia Navalnaya (née Navalny), she delves into the Ukraine war and the toll it has taken, not only on the men forced to fight, but on the women — mothers, wives, daughters — who, once again, struggle on against all odds. As the book ends, with the death of the author’s beloved grandmother Emma, the realization that Ioffe has lost her motherland once again sinks in. These pages revive it, briefly, letting us share her sadness about what once was and what could have been.

The Somerville-based Clea Simon’s next novel, The Cat’s Eye Charm, will be published Dec. 16.

Tagged: "Motherland: A Feminist History of Modern Russia, Julia Ioffe, Modern Russia, Russia, feminism, history

An excellent review of a sad history. Even today it seems that women are the bravest dissidents, and for some reason the pop artists, such as Diana Loginova and Nadya Tolokonnikova and friends, are the leaders. I often wonder at the silence of the Russian fine arts world — opera singers, dancers and choreographers, conductors and composers, musicians, painters and sculptors, to say nothing of the poets. Where are the Brodskys, the Mandelstams, the Solzhenitsyns? Easy for me to say, I know. Perhaps the best and brightest have already fled the country.