Visual Arts Review: A Painter Among Poets — Grace Hartigan’s “Gift of Attention”

By Lauren Kaufmann

The exhibit highlights the interplay between Grace Hartigan and the circle of modern poets who became her friends, supporters, and in some cases, patrons.

Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention at The Portland Museum of Art, on view through January 11, 2026

Grace Hartigan, Barbara Guest Archaics, 1968. Digital image courtesy of the Estate of Grace Hartigan/ACA Galleries, New York.

When you think of Abstract Expressionists, chances are you think of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, or Mark Rothko. Grace Hartigan (1922-2008) probably doesn’t come to mind. Hartigan’s story embodies the struggle that so many women artists have endured as they have toiled to gain wider recognition for their work. Hartigan is given her due in a new exhibition, Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention.

The show focuses on work that Hartigan created between 1952 and 1968. For this artist, it was a period of tremendous personal and artistic growth. For the country, it was a time of postwar reckoning, followed by major social and cultural upheaval. While visual artists were creating a new vocabulary that became the Abstract Expressionist movement, poets were also pushing boundaries, dispensing with traditional rhyme and meter. The exhibit highlights the interplay between Hartigan and the circle of modern poets who became her friends, supporters, and in some cases, patrons.

Hartigan was born in Newark, New Jersey, where she was married when she was 17, and gave birth to a son nine months later. Although she couldn’t afford to attend art school, Hartigan took night classes at an engineering college while working as a mechanical draftswoman in an airplane factory. When a co-worker introduced her to the work of Henri Matisse, Hartigan was inspired to study painting. In 1945, she moved from New Jersey to New York City with painter Isaac Lane Muse and their young son.

In the ’50s, Hartigan fell in with Abstract Expressionists living in New York, including Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, and Helen Frankenthaler. When Hartigan saw Pollock’s early drip paintings, she was impressed not only by the work, but also by Pollock’s all-consuming approach to making art.

While influenced by her cohort, Hartigan developed her own style, melding abstraction with figures and faces. Hartigan’s choice to merge abstraction with recognizable figures was a notable departure for an artist working in the ’50s and ’60s. It took guts and vision to devise a visual language that was her own, and that’s probably why Hartigan’s work was prized. The Persian Jacket, 1952, is considered to be the work in which Hartigan departs from pure abstraction. The Museum of Modern Art acquired the painting in 1953, making it the first work in its collection that was made by a woman from the Abstract Expressionist school.

Grace Hartigan, Grand Street Brides, 1954. Digital image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In Grand Street Brides, 1954, Hartigan depicts a group of brides with mask-like faces. She paints bridal gowns as blocks of white, delineated with thick black streaks. The painting successfully merges realism and abstraction. In 1955, the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired Grand Street Brides, a sign that Hartigan’s career was really taking off. It’s important to know that poet James Merrill, a close friend of Hartigan’s, played a key role in the museum’s purchase of the painting.

Merrill was one of several poets whose support was critical to Hartigan’s success. He was also a man of considerable financial means; Merrill’s father was Charles Merrill, founding partner of Merrill Lynch. The writer’s support, both emotional and financial, helped move Hartigan’s work from obscurity to public attention.

Hartigan befriended and collaborated with several other poets, and the exhibit includes a few pairings of paintings and poems. In fact, this back-and-forth between the visual arts and the written word is a major theme in the exhibition. While Hartigan chose subject matter that coincided with verse, some of the poets whom she befriended wrote art criticism as a way to supplement their income. Clearly, the relationships were mutually beneficial.

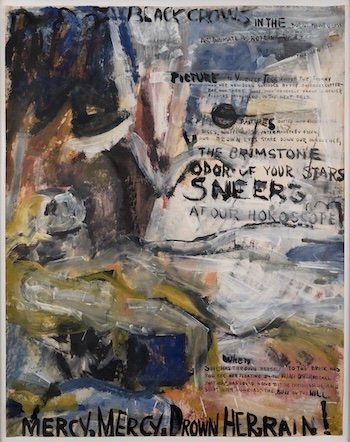

Grace Hartigan, Black Crows, 1952. Digital image courtesy of Nicholas Ostness.

Hartigan and poet Frank O’Hara became close friends, and the exhibit includes the coupling of O’Hara’s poem “Oranges I” with Hartigan’s painting, Black Crows (Oranges No. 1), 1952. The poem was one in a series that poked fun at the literary tradition of romanticizing rural life. Hartigan’s visual interpretation of the poem plucks phrases from O’Hara’s work, and she superimposes them on an abstract background that includes an emerging horizontal figure in the foreground.

The label for Black Crows includes a photograph of Hartigan and O’Hara at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, circa 1952. A handful of labels in the exhibit include black-and-white photographs of Hartigan with friends and fellow artists. The label for Masquerade, 1954, features a contact sheet of photos of Hartigan and her friends posing in her studio. The pictures inject a sense of whimsy, evoking the playful spirit of Hartigan’s fellow artists and poets. The snapshots add another dimension to the work because they attach faces to the abstract figures shown in the paintings. In Masquerade, Hartigan brings together her friends; she paints herself, wearing a hooded cloak and mask, into the group.

In addition to painting, Hartigan made collages and lithographs. The exhibit features a series of lithographs inspired by Barbara Guest’s poem “The Hero Leaves His Ship.” The work’s opening line — “I wonder if this new reality is going to destroy me” — had particular resonance for Hartigan, who was about to embark on a move from New York to Baltimore.

In addition to her creative collaborations with poets, Hartigan was intrigued and inspired by masks, and there are numerous paintings that allude to mask-wearing. The Masker, 1954, is a depiction of her friend, poet Frank O’Hara, a gay man whose identity, at that point in time, required masking. Several of the poets whom Hartigan befriended were gay: the ’50s were not an easy time for gays and lesbians. The trope of the mask has considerable significance given that this was a time of repression. Conventional societal norms had not been shattered, and the gay rights movement was still many years off.

As the title of the exhibit suggests, Hartigan’s place in the art world grew because her work increasingly drew attention — from fellow artists, poets, and people with influence. Her collaborations with poets speak to the richness that comes when a variety of artists strengthen their visions of the new by coming together. As a woman, living at a time when men’s work was more prized than women’s, Hartigan no doubt greatly benefited from the power and influence of friends like Merrill. Then, as now, people with money and power can open closed doors. Hartigan’s work certainly broke fresh ground, but her career also offers a lesson in how having friends and colleagues in high or notable places paves the path to success.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions.