Book Review: A Life Condemned — and Reclaimed: Gary Tyler’s “Stitching Freedom”

By Bill Littlefield

Stitching Freedom sheds necessary and welcome light on the sick and damaging history and current state of incarceration in this country.

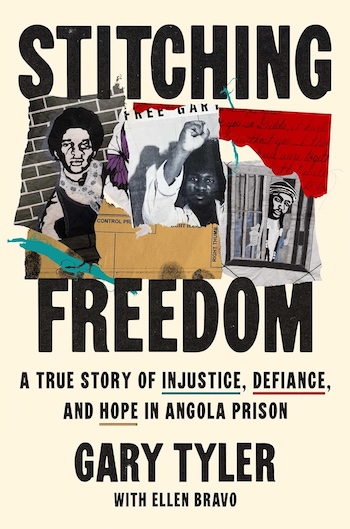

Stitching Freedom: A True Story of Injustice, Defiance, and Hope in Angola Prison by Gary Tyler (with Ellen Bravo), Atria, 272 pages, $29

The prologue of Stitching Freedom is titled “Man on Fire.” It presents the image of a man in flames, the victim of an attack by another man. The victim is burning and screaming on the tier above the one on which Gary Tyler is standing. Tyler can see the man. He can hear him. Tyler is in his fourth day on death row in Angola Prison in Louisiana. He is seventeen.

The image at the beginning of Gary Tyler’s story is powerful, certainly, and there is no question that prison can be a deadly place. But the image is also misleading, given the ultimate purpose and power of Stitching Time. Tyler’s intent is to provide readers with the understanding that he endured over forty years in Angola because he was befriended and mentored by wise and kind men who wanted to help him and knew how to do it.

Tyler, who is Black, was arrested for shooting a white child from the window of a school bus. Several students who were on the bus with Tyler testified that they’d seen him with a gun. But all of those students ended up recanting their testimony later, saying that the police had told them they’d go to prison if they didn’t say what they were told to say. One of the “witnesses” was a young woman with a child. She was told she’d never see her child grow up, because she’d be in prison for the rest of her life if she didn’t cooperate and lie.

Tyler’s trial was riddled with lies, contradictions, misapplications of the law, and various other outrageous flaws. No matter. At sixteen, Tyler was sentenced to death by electrocution. He avoided that fate because a series of court decisions eventually resulted in the recognition that sentencing someone who hasn’t yet reached adulthood to death is a spectacular violation of the U.S. Constitution.

But Stitching Freedom is less about injustice and violence than it is about Tyler’s determination to survive and even thrive. While incarcerated, he takes advantage of the tutoring and advice given by some of the older men he meets. He becomes not only literate but confident as a thinker and speaker. As Tyler writes, “In more ways than one, they saved my life.” He becomes active in the movement for justice for the incarcerated. He helps organize and expand the horizons of a drama group within the prison; eventually, he even takes some of their shows on the road. He describes the mission of that group as “a means of helping our fellow prisoners better themselves by letting their guard down, talking about their issues with people they could trust.” He develops a talent for quilt making that earns him recognition and awards for his artistry. The rank injustice of his conviction and incarceration earn the attention of all sorts of supporters, including various actors, musicians, and politicians. He so thoroughly earns the trust and respect of some of the corrections officers in the facility that they congratulate him and wish him well when he is finally released, more than forty years after his conviction.

The fact that Tyler was finally released from prison in 2016 should feel like a happy ending. But his release only came after a series of negotiations that left him feeling much less than satisfied. The district attorney’s plan was to reduce the murder charge to manslaughter, which has a maximum penalty of twenty-one years in prison. Having already served nearly twice that much time, Tyler would be released. As he writes, “I had been adamant to my attorneys that I would not get up in court and say I was guilty.” Though the state did not require this agreement, Tyler was compelled by authorities to “waive any rights to post-conviction relief and to pursue any compensation.” As he writes, “I had to give something up in order to get what I needed. I’m still disappointed by it – I should have been exonerated.”

Artist and spokesperson for justice, Gary Tyler. Photo: Dorian Hill

Fortunately, Tyler had earned considerable support among people of means. His case had been publicized. He’d become a representative for the fight against not only the death penalty and the injustice of the “justice” system, but the rise of racism and the injurious inclination to incarcerate poor and minority citizens in great and growing numbers. Tyler had a lot of help when he left prison. In that respect he was a great deal more fortunate than most men and women who’ve been incarcerated.

Stitching Freedom sheds necessary and welcome light on the sick and damaging history and current state of incarceration in this country. That Tyler found ways to surmount hideous, dehumanizing circumstances and went on to not only survive but inspire others is testimony to his own determination and the loyalty and energy of his many supporters. But nobody sheds forty years in prison without scars. As Tyler writes in the section of his book titled “Reflections,” “I’m still an individual walking around in daylight with a flashlight to find my way. I’m deeply aware of the four decades of freedom stolen from me, the limits on my life expectancy. I had my life condemned by a racist system. It’s outrageous that I still have to prove my innocence. I also know that the systemic injustice I faced decades ago continues to happen every day in this country.”

Bill Littlefield volunteers with the Emerson Prison Initiative. His most recent book is Who Taught That Mouse To Write? His most recent novel is Mercy (Black Rose Writing).

Tagged: "Stitching Freedom", American Prisons, Angola Prison, Gary Tyler