Visual Arts Review: Enduring Abstraction — Indigenous Artists Reclaim the Present at the ICA

By Lauren Kaufmann

By engaging with this work, museum visitors are likely to gain a greater appreciation for — and understanding of — the wide-ranging talents of Indigenous artists.

An Indigenous Present at the ICA/Boston, through March 8, 2026

George Morrison, Evening Layer. Signs of the Jasper. Red Rock Variation: Lake Superior Landscape, 1995. Image courtesy of the ICA/Boston.

Through the unifying theme of abstraction, the ICA/Boston’s An Indigenous Present celebrates the work of 15 North American artists. Whether through geometric design, photographic collage, landscape, or serial composition, these Indigenous artists employ a variety of styles, display a sweeping palette of color, and draw on a surprising array of materials. While the work spans from the 1940s until the present-day, all of it speaks to the value of abstraction as a powerful means of expression.

Indigenous artist Jeffrey Gibson and independent curator Jenelle Porter organized the exhibition. The pair have worked together for many years, and they collaborated on a book, also called An Indigenous Present, that came out in 2023. The concept for this show derives from that volume.

While the book, nearly 450 pages long, provides an analysis of work by 60 contemporary Indigenous artists, the exhibition presents a more focused lens. By focusing on a smaller group of artists, the curators can display several pieces by each of the artists represented, providing visitors with a fuller look at the output and growth of each. Taken collectively, the works convey the many ways in which Indigenous artists use materials, techniques, and personal perspective to counter conventional views of Indigenous art.

In addition to paintings, sculptures, drawings, and photographs, An Indigenous Present includes a sound installation by composer Raven Chacon, who, in 2022, became the first Native person to win a Pulitzer Prize for music. The exhibition also features several photographs and a four-minute video by Sky Hopinka, recipient of the MacArthur Genius Fellowship and an assistant professor in the Department of Art, Film, and Visual Studies at Harvard University. There is also a 30-minute video installation by Audie Murray, Bear Smudge, documenting a ceremony at dusk.

Although the exhibition does not include work by Indigenous artists from New England, Robert Peters, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, will be on site on selected dates in the ICA Bank of America Art Lab. Peters will present an interactive, family-friendly art installation inspired by his retelling of the story of Maushop, the mythical giant who, according to Wampanoag legend, created Cape Cod and the Islands. Peters’s participation is noteworthy; his background will provide visitors with valuable information about one of the area’s most significant local tribes.

A brochure that accompanies the exhibition includes a conversation between Gibson and Porter. In it, Gibson discusses how abstraction has become an effective mode for Indigenous artists. He says, “The minute you put a recognizable image into a picture, everything else becomes secondary. The power in abstraction is that it’s never fixed. Questions remain open.”

Gibson also notes that he and Porter approached the exhibit with the assumption that museum visitors possess a basic knowledge of Indigenous art and art history. They decided not to provide historical context, and for me this is an incredible leap of faith. Curators shouldn’t have to provide a complete history lesson, but some background information would have enhanced museum goers’ experience of the exhibit.

Edward Curtis, White Duck, a Hidatsa Indian wearing a headdress, taken c. 1908.

Many of us are familiar with Edward Curtis’s turn-of-the-century photographs of Native people that make up his famous project “The Vanishing Race.” The premise of Curtis’s work was that Indigenous people as a culture were dying out; he embarked on a project to capture their vanishing presence and history before it was too late. For many years, the myth of the “vanishing Indian” was used to rationalize colonial expansion and forced removals.

Despite having lost much of their land and some of their rights, Native people are still here. The title of the exhibition, An Indigenous Present, embraces the endurance of these artists, an assertion of survival that is firmly planted in the here-and-now. That said, for many of these artists establishing a foothold in the art world is no easy feat. Until recently, many museums did not exhibit the work of Indigenous artists, so it is significant that the ICA is displaying the striking work of so many, many of whom are still actively making art.

The first gallery sets the stage with the work of two older artists: George Morrison and Mary Sully. Morrison (1919-2000) was an Ojibwe from Minnesota. After attending the Minneapolis School of Art, Morrison moved to New York City to study at the Art Students League. His work was influenced by early 20th-century art movements, including surrealism, Dadaism, and cubism, and later, abstract expressionism. Morrison spent 50 years as an abstract painter, and 11 of his paintings appear in the exhibit, the earliest dating from 1946 and the latest from 1995.

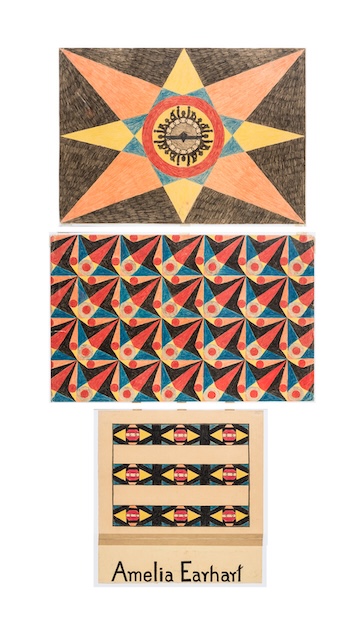

Mary Sully (1896-1963), a Dakota Sioux, is represented by nine of her “personality prints,” geometric triptychs of famous people made with colored pencil, graphite, and watercolor. In a portrait of Amelia Earhart, Sully fills the upper third with images of the single-engine propeller surrounded by silhouettes; the middle section features a series of spotlights, and the lower third contains an array of diamond shapes, similar to the patterns that Plains women added to rawhide containers. Sully worked in near obscurity and without patronage; her extraordinary work has only been exhibited in recent years.

Mary Sully, Amelia Earhart, c. late 1920s-early 1940s. Photo: courtesy of the ICA/Boston

The second gallery is thematically arranged around artists’ relationships with the ground, or landscape. This is a potent and complicated theme. Native people have always had a strong relationship with the earth; for thousands of years, they have endeavored to live in harmony with nature. Despite having lost much of their land to the US government, many Indigenous people maintain their traditional ways and continue to revere the land that they call home.

Teresa Baker’s Knife River, 2024, depicts a tributary of the Missouri River in North Dakota, a place rich with symbolism for Baker, a member of the Mandan/Hidatsa tribe. She uses buckskin, yarn, artificial sinew, and willow, and then places these materials onto artificial turf.

Sky Hopinka cuts up and rearranges landscape images to form luminescent compositions, adding a line of poetry to each image. Hopinka, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation in Washington state, explains that his method of creating photographic montages is similar to “the way a landscape can interact not only with the histories that are present, but the gestures that we make to beckon those histories. How can I construct these landscapes myself, and in some way obfuscate them, and protect them, in order to resist the idea of colonization through documentation.”

This gallery also contains a painting by George Longfish, Take Two Aspirins and Call Me in the Morning, You Are on Target, 1984. A blue and pink swirl of cloud hovers over the top of the composition, and a bright rectangle sits in the center, evoking a flag, or a stamp, or maybe a blanket. In the lower-right corner, there are two triangular shapes, perhaps suggestive of teepees.

The third gallery emphasizes seriality, work with repetitive colors and forms. Salmon Curl, 2023, and Salmon Curl II, 2025, by Sonya Kelliher-Combs lights up an entire wall with long rows of slender orange rectangular shapes. Kelliher-Combs, an Inupiaq and Koyukon Athabascan from Alaska, was inspired by sockeye salmon in the cold-drying process. Her work speaks to the central role that the salmon harvest plays in the lives of many Alaskans. Kelliher-Combs incorporates reindeer and caribou hair, everyday materials to a Native Alaskan.

The fourth gallery is graced by five works by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (1940-2025), considered to be the grandmother of modern Indigenous art. She was a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation in Montana. The five pieces represented here are painted in deep red, rust, and gold tones. Quick-to-See Smith called these works “inhabited landscapes.” She says that she intertwined her formalist training with abstract expressionism and her concern for things in the Indigenous world.

Kimowan Metchewais, Chief’s Blanket, 2002. Photo: courtesy of the ICA/Boston

Additional galleries showcase several works by the late Kimowan Metchewais (1963-2011), member of the Cree Nation, born in Saskatchewan. He made large works designed to be folded into portable pieces. In Chief’s Blanket, 2002, he combined ink, pigments, watercolor, and colored pencil to create an image that clearly evokes his Indigenous background.

There are several works by Kay WalkingStick, Cherokee and Anglo, who was influenced by the color field work of Helen Frankenthaler from the ’60s. The exhibition includes a wonderful piece, Apron Agitato, 1974, an image of her painting apron. The Italian word agitato means “moved” and in music, the term is used to denote a rapid tempo. The flecks of paint on WalkingStick’s apron look as if they were applied in quick, short strokes.

An Indigenous Present offers a lot to take in, and much of the work in this exhibition is revelatory in nature. By engaging with this work, museum visitors are likely to gain a greater appreciation for — and understanding of — the wide-ranging talents of Indigenous artists.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions.

Tagged: "An Indigenous Present", George Morrison, ICA/Boston, Jeffrey Gibson, Kay WalkingStick, Kimowan Metchewais, Mary Sully