Book Review: “I Knew a Man Who Knew Brahms” — Nancy Shear’s Harmonious Life in Music

By Jonathan Blumhofer

How our memoirist and the man who shook Mickey Mouse’s hand crossed paths is characteristic of the author’s good fortune and perseverance.

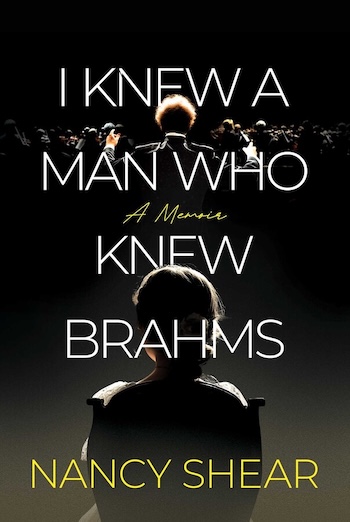

I Knew a Man Who Knew Brahms by Nancy Shear. Regalo Press, 338 pages, $32

“The key to the mystery of a great artist,” Leonard Bernstein once said, “is that, for reasons unknown, he will give away his energies and his life just to make sure that one note follows another … and leaves us with the feeling that something is right in the world.”

“The key to the mystery of a great artist,” Leonard Bernstein once said, “is that, for reasons unknown, he will give away his energies and his life just to make sure that one note follows another … and leaves us with the feeling that something is right in the world.”

Nancy Shear’s memoir, I Knew a Man Who Knew Brahms, doesn’t quite unravel that riddle as it pertains to conductor Leopold Stokowski. Then again, the Marylebone-born maestro, for whom Shear worked as an assistant during a spell in the 1960s, isn’t the main character in this tale. Neither is the figure referenced in the title — one Raoull Hellmer, who makes a cameo on page 62 and then recedes into the mists of history as discreetly as he’d emerged from them.

Rather, the book’s star is Shear herself. The product of an unhappy, abusive marriage, the author’s pluck, focus, and determination to rise above her situation are the traits that quietly tie this story together. That, and the personal foibles of some of the 20th-century’s great artists.

Stokowski certainly counted among them, though by the time he and Shear first crossed paths in the early ’60s, he was in the twilight of a very long and productive life. Born in England in 1892, the conductor had been music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1912 to 1936. Succeeded by Eugene Ormandy, whom Stokowski detested (the feeling was mutual), he furthered his legend with orchestras, recordings, and film appearances in England and the United States — not to mention a high-profile marriage to Gloria Vanderbilt. By the time Shear’s tale begins, in 1960, the great maestro, with his famous shock of white hair, was returning to his old Pennsylvania stomping grounds for the first time in decades.

How our memoirist and the man who shook Mickey Mouse’s hand crossed paths is characteristic of the author’s good fortune and perseverance. Unable to afford tickets to the Philadelphian’s performances, Shear started hanging out by the Academy of Music’s stage door until, one afternoon, the teenager caught Ormandy’s attention. He brusquely arranged for her to have a concert pass and, before long, she was treating the place like a second home.

A chance ramble backstage in 1963 brought Shear to the orchestra’s library, where she struck up enduring friendships with librarian Jesse Taynton and assistant conductor William Smith. Helping out in the library after school — as well as attending rehearsals and concerts — led, in February 1964, to her meeting Stokowski. The rest, as they say, is history.

Once she agreed to work for Stokowski, Shear commuted between Philadelphia and New York City, where the conductor lived, balancing part-time work in the orchestra’s library (and, later, college) with attending to the maestro’s various needs, from the musical to the gastronomic. Among her most significant roles in Stokowski’s life at this point seems to have been serving as a companion and sounding board: for all the bright stage lights and the paparazzi that had trailed his every move, Stokowski in his 80s comes across as, essentially, a lonely old man.

Not that his opinion of himself — or his libido — appeared to have slowed down. A notorious lothario, Stokowski was uncharacteristically paternalistic with Shear. Their relationship remained platonic, though there’s an undercurrent of attraction in several scenes and, near the end, an unfortunate blowup after the 93-year-old provocatively kissed Shear in front of his long-suffering live-in secretary, Natalie (who harbored feelings of her own for him).

Nevertheless, Shear’s experiences working with Stokowski seem to have been mostly pleasant. Despite her assignment, she managed to have an active social life and recounts several romances, though none of them possessed the passion and sweep of her relationships with Stokowski and, later, the cellist-conductor Mstislav Rostropovich.

At the same time, Shear is very alert to the challenges of a young woman navigating professional life on her own, whether 60 years ago or today. She writes knowingly about moments of abject sexism, like her interview for a position for which she was clearly qualified — but the manager had no interest in hiring a woman. She tells of members of the Philadelphia Orchestra actively shielding their 17-year-old colleague from lecherous visiting artists. And she meditates with the clarity and understanding of one who’s had time to ponder the ambiguities of her relationship with Stokowski.

At the same time, Shear’s memoir is about not being derailed by obstacles. Instead, her story is, partly, about boldly seizing the moment — sometimes recklessly grabbing hold of it (like when she jetted off to Moscow over New Year’s to check in on Rostropovich at the height of the Cold War) — and reaping the rewards. Though she doesn’t lavish details on her later professional successes, Shear paints a vivid picture of how well-directed grit, talent, and tenacity can be applied from youth and continue paying dividends as life proceeds.

There’s also a welcome reappraisal of Stokowski, whose star has dimmed somewhat since his death in 1977. Shear remains a fan, not just for the intensity and electricity of his music-making, but also for its breadth. Though aspects of his process remain controversial (not least the habit of reorchestrating passages the conductor didn’t think spoke with the right degree of clarity), his example of risk-taking in the name of musical excellence has a long pedigree — and his actions, as Shear notes, were often in response to what he gleaned from rehearsing with orchestras.

In these musical discussions, as well as the ins and outs of librarianship, Shear proves herself an able writer with a keen eye for detail and a too-rare ability to break down musical terms, concepts, and history into easily digestible morsels. Fear not, nonmusically-trained reader: Nancy Shear’s got your back. (And don’t worry, cognoscenti —you’ll find plenty of interest here, too.)

For all the joy, wonder, and excitement that pervades these pages, though, there’s a ruefulness that hovers over much of this book. The ’60s and ’70s remain very much a part of living memory, but the cultural world Shear relates — with its Old World giants, its deeply literate audiences, its attentive media — is, for better or worse, no longer with us. That so much can change in less than a lifetime is one of the hard, unspoken truths of this memoir.

A constructive corollary — and it’s demonstrated time and again in Shear’s biography — is the power and value of human agency. “Time, like an ever-moving stream,” as Isaac Watts once put it, “bears all its sons away.” Perhaps it’s best, then, to embrace the day like Shear did, unapologetically and proactively. After all, you never know what interesting characters you’re going to meet along the way.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: "I Knew a Man Who Knew Brahms", Leopold Stokowski