Book Review: “Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What To Do About It” — Brushing Away Platform Decay

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

Journalist Cory Doctorow transforms what might be seen as a viral complaint into a theory of digital decay, tracing how the internet’s early architecture of openness curdled into a landscape of monopolized chokepoints.

Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What To Do About It by Cory Doctorow. MDC Books, 352 pages

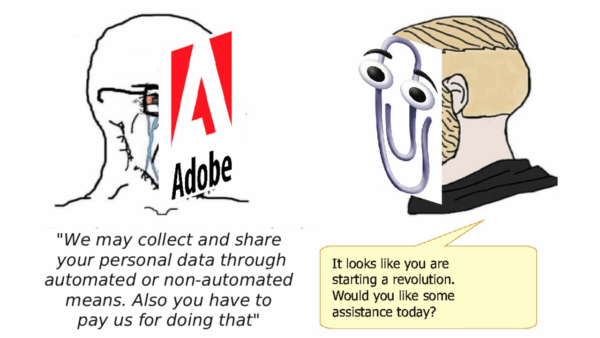

In August 2025, social media users began changing their profile pictures to Clippy—the animated paperclip assistant from Microsoft Office who first popped up in 1997. For many, the character evoked an idyllic technological past, a time of innocent collaboration that stands as a pointed counterpoint to today’s regime of manipulative extraction. The case for the avatar was made by YouTuber Louis Rossmann, who said, “Clippy never tried to sell your data—he just wanted to help.” In reaction to such hellacious news as Meta’s alleged tracking of teenage girls’ deleted selfies (the better to target them with beauty ads), Clippy serves as a symbol of a paradise lost: the early promise that the internet would be about connection, enhancement, and liberation.

In August 2025, social media users began changing their profile pictures to Clippy—the animated paperclip assistant from Microsoft Office who first popped up in 1997. For many, the character evoked an idyllic technological past, a time of innocent collaboration that stands as a pointed counterpoint to today’s regime of manipulative extraction. The case for the avatar was made by YouTuber Louis Rossmann, who said, “Clippy never tried to sell your data—he just wanted to help.” In reaction to such hellacious news as Meta’s alleged tracking of teenage girls’ deleted selfies (the better to target them with beauty ads), Clippy serves as a symbol of a paradise lost: the early promise that the internet would be about connection, enhancement, and liberation.

Rose-colored, to be sure. The cyberpunk dystopias of the ’90s-’00s (The Matrix, etc) had foretold that it was all a lie. But that remained the idyllic language of the pre–dot-com techno-sphere. For many it is a living memory, and it still carries a nostalgic whiff of web Kumbayah. Our present oligopolies no longer have any need for the illusion now that their rapacity has spread through every nook and cranny of human experience. And that is where we are now; our angst about the hollowing out of the internet experience has turned into a full-blown malaise, a product of what has become enshittification, the planned atrophying of just about everything except the commanding power of our tech-lords.

This debilitating fatigue—what Rossmann channels through irony and nostalgia—is what Canadian-British journalist Cory Doctorow examines with acuity in Enshittification. The word has already entered the vernacular— it was tagged the word of the year by the American Dialect Society in 2023 and by Australia’s Macquarie Dictionary in 2024. Doctorow supplies the term with structure, history, and political depth. His book transforms what might be seen to be a viral complaint into a theory of digital decay, tracing how the internet’s early architecture of openness curdled into a landscape of monopolized chokepoints.

For Doctorow, the problem with the “platform economy” is that it reintroduces the middleman, the very figure that the early internet — and even today’s “five giant websites” in their nascent phases — claimed to eliminate. The fundamental flaw of platforms lies in their inevitable compromised structure as two-sided markets, serving both users and businesses. The parity they pretend to maintain between these groups — the delicate division between users and customers — inevitably collapses. Users, the weaker party, are crushed by the massive consolidation of resources on the business side, groomed to manipulate and exploit. From the outset, this imbalance doomed the online ecosystem to oligopoly. Doctorow offers a Marxist-style history of the evolution of platform enshittification—pathological decay in users is empowered through the unleashed force of capital accumulation and extraction. Doctorow’s sense of humor only sharpens the depressing point: beneath the satire lies a moral economist asking whether a truly participatory, user-centered internet can survive within a system that rewards the strategies of total enclosure for the sake of unending profit.

Doctorow shows how Amazon, Facebook, Google, YouTube, TikTok, Spotify, and Twitter all follow the same bait-and-switch trajectory: initially serving users only to exploit them through engineered dependence. Each combines a vision of market dominance with up-to-the-minute psychological manipulation. Our most intimate data is being algorithmically supercharged so it can be maximally monetized. Or they take a momentary respite from that predatory model by turning to pay-to-play schemes. The result is a digital economy that is not from connection but profiting from captivity — one-stop shopping forever. Politically, it signals the perversion of the public sphere into rentable pipelines expressly tailored to manufacture consent.

Doctorow’s critique is more than nostalgia for the “open web,” where our dim awareness that something is awry is itself commodified into vibes. Nor is this a work of technical historiography. Greater technological-historical literacy has its revelatory value — for instance, it would be helpful to understand how frameworks like React helped enable the seamless, endless interfaces to shape the modern attention economy. But Doctorow explicitly rejects media literacy and consumer awareness as solutions. Instead, he argues, compellingly, that only a thorough redistribution of power will be able to produce meaningful choices for users: antitrust enforcement, interoperability mandates, and the rebuilding of public institutions and watchdogs capable of restraining overweening platform monopolies.

That is all to the good, but Doctorow’s most striking contribution lies in how he traces that enshittification is maintained through entrapment. Platforms don’t merely exploit users; they disable any convenient means of escape—by outlawing interoperability, walling off APIs, and punishing developers who attempt to rebuild lost connections. His call for “adversarial interoperability” takes a technical and political form — it is rooted in the right to rewire the digital world against the dominion of corporate consent. In Doctorow’s view, interoperability once functioned as the internet’s immune system—the ability for users and rival developers to connect services freely, to build alternative clients, and to be able to move their data between ecosystems. Its deliberate erosion — through DRM, legal threats, and proprietary standards — ensures user dependency: the more a platform enshittifies, the harder it becomes to leave. He also turns his attention to the engineers themselves. Once imbued with what he calls “vocational awe”—a belief in their world-saving mission—tech workers have become both instruments as well as victims of the system’s moral decay. Their disillusionment, reported here and elsewhere, mirrors our own.

To his credit, Doctorow doesn’t fold our angst about enshittification into commodified pop sociology. It is equally important that he doesn’t reduce the problem to a materialist critique of technology. In isolation, technology is neutral; ideology is what mediates and distorts material relations. It is our politics — rather than capital in the abstract — that drives enshittification. Ideology is how capital’s incentives are lived, rationalized, and enforced; it has the power to bend economic imperatives in welcome moral directions. This distinction is crucial in an age when, as the saying goes, “if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.” To that idea, we might add Marx’s old definition of commodity fetishism: the transformation of social relations between people into material relations between things—a sleight of hand that conceals the alienation at the heart of our economic order. Internet users are now being turned into virtual, commodified avatars. It is any surprise that the human beings trapped behind the algorithmic curtain feel—however dimly or painfully—the rupture in the material bonds between each other and the world around them.

Jeremy Ray Jewell writes on class and cultural transmission. He has an MA in history of ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.