Visual Arts Review: Portia Zvavahera’s “Hidden Battles / Hondo dzakavanzika” — An Invitation into the Maze

By Jonathan Bonfiglio

Portia Zvavahera’s seven large paintings, including three new pieces, focus on the umbilical nature of her dreams, in particular those featuring imagery which reaches out across unusually linked cultural, historical and religious touchstones.

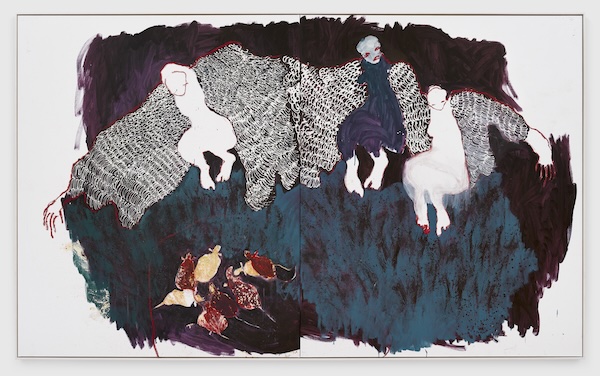

Portia Zvavahera, Tinosvetuka rusvingo, 2024. Oil based printing ink and oil bar on linen. Courtesy the artist, Stevenson and David Zwirner. Collection of Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, India. Photo: Portia Zvavahera

The uncontainable landscape of contemporary art is full of tensions. To some extent, in fact, the tensions are part of the allure, offering a parallel universe of thought, language and representation, one where the only intellectual shibboleth is that of fixed interpretation.

No surprise, then, that often it is life’s outsiders, its poets and vagabonds, who choose to inhabit its limitless corridors. They are not alone in embracing imaginative freedom: close behind them walk the art-market extractivists, hucksters and shysters recognizable by their swagger, akin to that of the real-estate agent who believes he’s won the only argument which ever mattered. Just because we’re used to it doesn’t make it normal. By any measure these are strange bedfellows, locked in an unholy embrace.

Curators, too, have it tough, especially so when charged with mediating amorphous work, as is evident in the case of Portia Zvavahera: Hidden Battles / Hondo dzakavanzika at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, through January 26, 2026. Zvavahera’s seven large paintings, including three new pieces, focus on the umbilical nature of her dreams, in particular those featuring imagery which reaches out across unusually linked cultural, historical and religious touchstones. It’s a tricky proposition for the curatorial eye, which understandably circles around the question of what to share (or not share) with the viewer. Rather than being a question, however, it is really best considered as a trap. Do you choose to share some information, thus allowing entry points to the work, but at the same time narrow the viewer’s agency in interpretation? Or do you say nothing at all, and leave the work to speak for itself, trusting the audience, but also running the risk of leaving them floundering in confusion? Contemporary art evangelizes the language of the visual, and how it should be allowed to speak for itself, unmediated, but these are high seas, and easy to drown in.

Portia Zvavahera, Ndirikumabvisa, 2024. Oil based

printing ink and oil bar on linen. Courtesy the ar

tist Stevenson and David Zwirner. Photo: Jack Hems

In Hidden Battles / Hondo dzakavanzika, curators Ruth Erickson and Meghan Clare Considine have chosen the former route. We are told that Zvavahera’s work lies somewhere between the figurative and abstract, that it merges painting and printmaking, that it uses imagery from both her Zimbabwean Shona heritage as well as the African Pentecostal tradition of her upbringing, that a major focus is on the animals which appear in her dreams, from eagles (of importance in Shona culture) to snakes (imagery from the ever-ubiquitous Christian Bible) to rats (cross-culturally ugh). All of this enhanced by the fact that the artist considers her practice to be akin to an act of worship.

The landscape of our subconscious has been fertile ground for cultural representation since as far back as far back goes, and in all likelihood it goes back even further than that. More recently, the likes of Salvador Dalí, Leonora Carrington, and Max Ernst have made dreams into compelling distorted mirrors, without any having ever been able to shake the specter of the question which dogs all such all surrealistic visions: what does it all mean? It’s a culturally unavoidable question, and addressing it by adding complementary information makes perfect sense.

Choosing an analytical entry point to a field of dreams is not without consequence, however, especially because the knowledge economy is a one-way street; once we know something it is almost impossible to forget. Whilst this undoubtedly makes the work more accessible, it also foists upon the viewer a sort of checklist of items. In this case, it runs the risk of inviting a neat breakdown of Zvavahera’s work into component parts. If Zvavahera was more reductive in style, there would be less risk of clinging to the handrails, but her work is just so goddamn enveloping it makes you want to forget everything you ever knew. It sucks you out of yourself to the point that you lose your own shape in the viewing. In part, it’s the scale of the paintings, but far from just that, it is because Zvavahera’s dream landscapes achieve art’s great intangible goal: they have a viscerally beating heart, and an accompanying soul.

It’s also a point of tension for the writer, because what can you possibly say (how can you possibly react) to work which denudes you, strips you to a point of absence.

Ultimately it’s a choice between interacting and inhabiting, both of course valid (no readings outlawed here). Sometimes curators fear allowing the public, untooled and unprepared, into an imaginative maze, and that is unfortunate. It is only by becoming lost in the labyrinth that viewers can start to work through the implications of the fact that the maze, rather than being an external construct, is in fact an essential part of us — and that all the art we will ever witness is a self-portrait.

As well as writing about art in the American continents, Jonathan Bonfiglio covers Latin America for The Times in London and regularly broadcasts for the likes of LBC (UK), ABC (Australia) and TalkRadio (UK). His new podcast “Less Time Than Ideas – Art Across the Americas” is available across streaming platforms.