Book Review: “Lion Hearts” — Dan Jones Brings His Essex Dogs Saga to a Stirring Close

By Clea Simon

Novelist Dan Jones excels in reimagining the life of common people in wartime, in particular a small group of English fighters embroiled in the so-called Hundred Years War (1337–1453) between England and France.

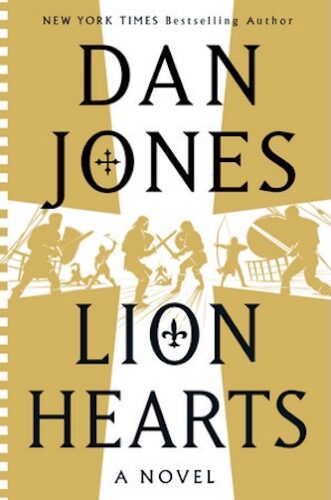

Lion Hearts by Dan Jones. Viking, 384 pp., $30

Historical fiction is one of those catch-all genres, encompassing works by multiple Booker winner Hilary Mantel and the romance-oriented retellings of Diana Gabaldon. As a genre author, I’ll defend them all as serving different purposes for different readers, as proved by the number of authors — James McBride, Chris Bohjalian, Daniel Mason, Barbara Kingsolver — who have chosen to set an engaging story in a well-researched past.

Historical fiction is one of those catch-all genres, encompassing works by multiple Booker winner Hilary Mantel and the romance-oriented retellings of Diana Gabaldon. As a genre author, I’ll defend them all as serving different purposes for different readers, as proved by the number of authors — James McBride, Chris Bohjalian, Daniel Mason, Barbara Kingsolver — who have chosen to set an engaging story in a well-researched past.

What Dan Jones does, however, is excel in a very specific subgenre of the field. Working in roughly the same format as Bernard Cornwell (The Last Kingdom), Jones vividly reimagines the life of common people in wartime, in particular a small group of English fighters embroiled in the so-called Hundred Years War (1337–1453) between England and France, a saga that has played out in a trilogy that concludes with the new, and quite wonderful, Lion Hearts.

We first met Jones’s fighters in the opening of the first book in the trilogy, 2023’s Essex Dogs, as they landed in Normandy in 1346 as part of the English King Edward III’s invasion of France. More or less led by Loveday FitzTalbot, an older soldier who serves as the heart of the series, the Dogs are a motley crew of misfits, mercenaries, one priest, and two trained archers, united primarily by the desire to survive the 40 days of service for which they’ve enlisted under the noble Sir Robert le Straunge and then collect their pay.

Needless to say, the English invasion doesn’t go as planned and, as the Dogs hack and hide their way through the battle of Crécy, we come to know their idiosyncrasies and quirks, as well as the personal histories that brought them to this bloody battlefield.

The second in the trilogy, 2024’s Wolves of Winter, opens in 1347 with a much-depleted crew of Dogs at the infamous Siege of Calais, a nearly year-long blockade most notably evoked by Rodin’s sculpture of “The Burghers of Calais,” the municipal leaders who sacrificed themselves in the hope of saving their port city. Of course, in Jones’s take, nobody acts from truly noble motives, As King Edward strangles the French holdout, hoping for an end to the larger war, the Dogs are separated, at various times outside and inside the besieged and starving city.

Lion Hearts, pitched as the final Essex Dogs book, brings the war home, both literally and in its fighters’ minds. It’s 1350, and Loveday has retired and is running a pub in the English port town of Winchelsea. The land of his youth has changed, however. The Black Death has killed roughly half the English population, and although the scarred and traumatized veteran has survived the plague, he is suffering from its economic aftershock. The tavern he has purchased with his long-overdue battle pay is in lousy shape, and the post-plague lack of workers and wobbly economy has placed the Green Lion, where he lives with his new love Gilda and her young son, on the brink of ruin, its rotten thatch roof leaking and a wealthy competitor threatening to take over. To make matters worse, Castilian pirates are raiding English ships, disrupting the trade that keeps Winchelsea alive.

After his mounting debts suck him into a smuggling ring, the old soldier is desperate — and when some of the surviving Dogs show up, he sees a way out. Until, that is, Rigby, the simple-minded nephew of one of the Dogs, is kidnapped by the pirates, drawing the remnants of the ragtag unit back into battle.

Not all the Dogs are in such desperate straits as Loveday, however. In a parallel plot line, Romford, a sad youth at the series’ start, has — against all odds — become a squire in the king’s court, a position he hopes to use to locate and then aid his old comrades. As he becomes involved in the political machinations of his heavily indebted master (a historically accurate Sir Thomas Holand), however, he finds he must utilize the cunning he learned from the older Dogs to survive. Meanwhile, another of the crew, believed dead by the end of Wolves, resurfaces in an unlikely place, a little crazier and thirstier for blood than before.

Does that sound dark? It is, but also vibrantly alive and realistic, peopled with characters who care more about their bellies and their lusts (or, as they’d put it, their “pintles”) than the politics of those who command them this way and that.

A Cambridge-educated historian and author of such popular histories as The Plantagenets: The Kings Who Made England, (a New York Times bestseller), Jones is a lovely writer, adept at conveying the inner lives of the men (and the occasional woman) living in such turbulent times by way of simple yet evocative language in a tight third-person voice. The latter is generally centered, in this book, on Loveday and Romford. “He made his voice gruff to try and cover its wobble,” he says of Loveday at one point, while at another, the veteran notes to himself: “Loveday reminded himself he no longer cared about such things. About ships and fighting and king’s armies and missions here or there or anywhere else. Yet he stood and watched the ship for a long time.”

Although such quiet insights have powered both of the earlier books in the trilogy, in Lion Hearts, Jones explores new depths in his characters. For example, Loveday repeatedly avoids conflict, telling himself he’s doing it for Gilda, even as he mentally plots out how a fight would go:

“He knew that in the next few heartbeats he would step his left foot as close to the boy’s as possible, feint to clip him around the ear with his left hand, and then, using the heel of his right hand, throw a full-strength blow …” He pulls himself back, but the impulse lingers: “He felt something dripping on his arm and looked down, expecting to see blood. But it was only rainwater coming through the roof.”

Largely because of such concrete and realistic emotional detail, Jones’s work is infinitely superior to the massive sagas penned by Ken Follett (The Pillars of the Earth), despite their common medieval setting. His characters are not only better drawn, but their private battles — from Romford’s early struggle with addiction to Loveday’s PTSD — are far more specific and convincing.

A better comparison would be Barbara Tuchman, if the author of A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century had turned her hand to fiction. Characters like Holand, Joan (“the Fair Maid of Kent”), and Richard Large (the sergeant-at-arms who serves as Loveday’s dubious savior) are based on historical figures (in the case of Large, the name of an actual Winchelsea resident, Hugh de Lavenham, whom Jones describes as “a gang leader who went into royal service”), and Jones includes a bibliography for those who wish to delve further.

As for Loveday, his fighting days appear to have truly ended with Lion Hearts. And the rest of his crew? Although this book has been pitched as the last in a trilogy, the final scene hints at adventures to come, as does a note in the epilogue about yet another problematic encounter “as the Essex Dogs may in time discover.” As horrible as war is in any era, this reader would gladly venture forth again with these Dogs.

Clea Simon is the Somerville-based author most recently of the novel The Butterfly Trap.