Visual Arts Review: Immersed in Memory and Flight: Andrae Green’s “Paradise/Mash-Up” at the BCA

By Jonathan Bonfiglio

For the artist Andrae Green, where land and sea meet is not a line, but an immersion.

Paradise/Mash-Up: Andrae Green at the Boston Center for the Arts, Mills Gallery, 551 Tremont St., Boston, through November 8.

Andrae Green, The Deal Behind Sunset, 2025. Photo: courtesy of the artist

There’s something about diving. The weightlessness, perhaps the fall, but not just a fall, more of a casting off, a liberation, an attempt at flight without wings.

And in that leap, a sense of losing the constraints of form. We are no longer rooted to the ground, or our physical selves. We jump off a solid object, out into thin air before crashing into water below, but above all we jump out of ourselves.

Way back, in our youth, we dove in brazen challenges, repeating irrepressible attempts to bend the laws of the universe to our will. Later, as the lights dim, we dive to remember who it was that we were, and to catch a glimpse of ourselves in that fleeting, weightless moment.

Plainly put, when we dive, we dive in time.

This loaded moment of midair capture is a recurring motif in the work of Jamaican-born Andrae Green, liberally featured in the exhibition Paradise/Mash-Up. That image is not alone; it exists alongside water, coastlines, and the assorted representations of the lived port cities of Green’s native Kingston, Jamaica, and Boston — the latter now his home. Often structurally painted to resemble collages — perhaps reflecting how memories reshape themselves over time (do we remember an act or do we remember the memory of the act?) — the works include beach balls, cargo ships, sailboats, and lighthouses, among others. Many are set at a border, often at the point where water meets land, serving as a reminder of English writer Geoff Dyer’s memorable line of how perhaps “all exiles are drawn to the sea, the ocean.”

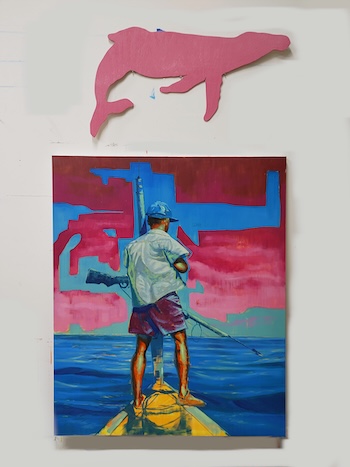

Andrae Green, Ode to Meta, 2024. Photo: courtesy of the artist

The depicted subjects are noteworthy in themselves, but they are transformed by Green’s distinctively characteristic use of color, which across much of his work achieves the feat of selecting the sepia tint of time-gone-by and deepening it to its essence. Not all Green’s work follows the same color scheme, though. A number of pieces, in particular the “Unrequited Love” and “View from Kingston Harbor” series, are depicted through an oceanic blue that is all-encompassing. The color dominates the view, which means, as with the water it emanates from, it fails to respect boundaries. For Green, where land and sea meet is not a line, but an immersion.

Andrae Green, Stories of My Father That I Never Heard But Believed, 2024. Photo: courtesy of the artist

There are two works within Paradise/Mash-up that feel especially emblematic. The first of these is Icarus 2 – Flight, a painting fractured into sections and layers, pieced together, in which we catch various moments of a young man stepping off a steep rock and entering into an aforementioned dive. The piece is all gravity, from the suspended crane hook at the top of the picture to the beach ball caught teetering on the edge of a pool. It is then later captured falling. And then, of course, there is the man himself. Off-center, we seem to see him in freeze-frame as he stretches into a jump, his arms yearning to transfigure into Icarus’s golden wings.

There are multiple other works in which Green envisions arms taking on the aesthetic of wings, in particular the LEEP series of paintings, where human forms are imbued with suggestions of a bird in full flight.

The other highlight is Stories of My Father That I Never Heard But Believed. This elusive, playful work presents a man standing precariously on the prow of a wooden skiff, his back to the viewer as he looks out ahead and into the water beyond the vessel. Partially obscured in his hands is a fishing rod that might also be a gun or a speargun. Above the painting is the stand-alone cutout of a whale. The piece clearly plays to the trope of the fisherman’s exaggerated size of catch but, in a curious sleight-of-hand, Green uses the title to encourage us yet again to think about the power of an imaginary lost time. “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there,” observed L.P. Hartley in 1953. The work of Andrae Green explores a similar premise, perceiving this twilight zone as a land of fables where we are perhaps the freest to live our best lives. Although — as with memories — it can only ever be a place we inhabit alone.

As well as writing about art in the American continents, Jonathan Bonfiglio covers Latin America for The Times in London and regularly broadcasts for the likes of LBC (UK), ABC (Australia) and TalkRadio (UK). His new podcast “Less Time Than Ideas – Art Across the Americas” is available across streaming platforms.