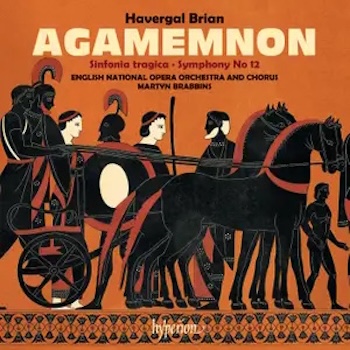

Classical Music Album Review: Composer Havergal Brian — A Less Than Robust Musical Harvest

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Across his career, British conductor Martyn Brabbins has used his bully pulpit to bring to light all sorts of deserving, unfamiliar repertoire, including the music of Havergal Brian.

Some composers are revered, it seems, from birth. Others only find critical and popular favor after they’ve died. For most, it’s some combination of those trends—or complete neglect.

Some composers are revered, it seems, from birth. Others only find critical and popular favor after they’ve died. For most, it’s some combination of those trends—or complete neglect.

Then there’s Havergal Brian. Born in 1876, he achieved a standard of success in the years leading up to World War 1. A domestic crisis presaged several fallow decades and it wasn’t until the ’50s that his reputation as a composer began to get reconsidered. As it happened, those years saw a prodigious outpouring of music: Brian wrote no less than four operas and twenty-seven symphonies between his retirement in 1940 and death in 1972.

Those reams of music didn’t exactly make him the second coming of Elgar, but they did gain the composer a devoted cult following which, mid-century, counted Leopold Stokowski and Sir Malcolm Sargent among their number. Today, Martyn Brabbins is chief among the elect.

Across his career, the British conductor has used his bully pulpit to bring to light all sorts of deserving, unfamiliar repertoire, much of it by his compatriots. His new recording of two of Brian’s symphonies (Nos. 6 and 12), as well as the opera Agamemnon, with the Chorus and Orchestra of the English National Opera, continues the tradition, though the musical harvest this time around is a bit less robust.

Among the primary issues, in the symphonies, is a mismatch between form and content. No. 6, subtitled “Sinfonia tragica,” certainly wears a spirit of grief on its sleeve: the high-tessitura brass writing wails, sometimes with uncomfortable urgency.

Yet the musical arguments often feel half-baked or ill-considered. Since this isn’t a long essay (the whole piece clocks in around twenty minutes), what it really needs are either concise or pithy motives or fewer ideas that are more thoroughly and richly developed. But Brian went for a middle ground and the results are choppy and expressively antiseptic. Of course, maybe that was his point and, if so, more power to him. But the fact remains that the score sounds like the uninspired noodlings of an amateur.

The Twelfth is even shorter, lasting only about twelve minutes, but hardly more satisfying for its concision. Again, a jumble of thematic and motivic ideas emerge. How they’re related is anyone’s guess. There seem to be echoes of Hollywood film music (good stuff, like Rosza and Hermann) though nothing quite sticks; even the best thing on the whole album—a slowish riff in the Lento that calls to mind Holst—gets blown up before it has a chance to fully mature.

Composer Havergal Brian.Photo: Wikimedia

Then we have Agamemnon. Being unfamiliar with Brian’s four other operas, I’m in the dark as to how representative this treatment of the great Greek tragedy is in relation to his other theater music. On the plus side, the score has a couple of things going for it, at least early on. The opening minutes are rhythmically taut and fairly tight, motivically. The vocal writing is angular and sometimes ungainly, but it’s largely idiomatic and, on this recording, is unfailingly well sung.

Where Agamemnon runs into trouble, though, is in its setting of John Stuart Blackie’s 1906 Everyman translation of Aeschylus. Too often, especially as it builds towards its denouement, the wordy libretto undercuts any sense of urgency the music might, on its own, create.

What’s more, Brian didn’t seem to care much for delineating his characters, musically. Accordingly, pretty much everybody—Clytemnestra, Cassandra, Agamemnon, the Watchman, the Herald—sings the same sort of blustery music, regardless of whether they’re supposed to be evoking wonder, anger, joy, fury, mystery. The results are dramatically flattening (and that’s without even getting into Brian’s most obnoxious pet: the overused combination of cymbals and snare drum).

Nevertheless, Brabbins and Co. deliver about as fine a performance of this neglected effort as you’re likely to hear. Eleanor Dennis’s Clytemnestra has no trouble holding her own with the orchestra—or blending well with John Findon’s swaggering Agamemnon. Stephanie Wake-Edwards’s Cassandra does admirably in the opera’s most interesting and satisfying aria (“Ha! The house of the Atridae!”), while Robert Murray’s Watchman and Clive Bayley’s Herald/Old Man are both strongly etched.

Oddly, the ENO Chorus’s contributions sound disembodied and distant. But that’s par for the course with the disc’s engineering, which doesn’t blend the orchestra particularly well in any selection—or take excessive care to balance Agamemnon’s cast of voices and instruments. As a result, climaxes often feel constrained and shrill, and smaller moments are boxy.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.