Book Review: “Tech Agnostic” — Was the Creation of the Computer Chip our Original Sin?

By Preston Gralla

Although Greg Epstein’s analysis and critique of what he calls a tech religion are on target, his solutions for undoing its damage are bland, vague, and toothless.

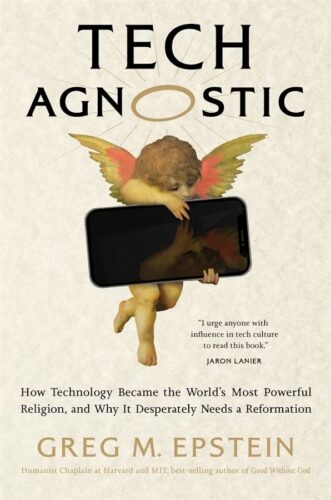

Tech Agnostic: How Technology Became the World’s Most Powerful Religion, and Why It Desperately Needs a Reformation by Greg M. Epstein. 368 pages. MIT Press, 368 pages, $29.95

It’s a timeworn cliché to say technology is our new religion, a quick, simplistic shorthand way of summarizing tech’s many excesses. In Tech Agnostic, Greg Epstein sets out to prove how true that cliché is, by performing a rigorous analysis of the way technology has the same kind of commandments, strictures, hierarchies, and hold on its believers that form the underpinning of traditional religions like Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

It’s a timeworn cliché to say technology is our new religion, a quick, simplistic shorthand way of summarizing tech’s many excesses. In Tech Agnostic, Greg Epstein sets out to prove how true that cliché is, by performing a rigorous analysis of the way technology has the same kind of commandments, strictures, hierarchies, and hold on its believers that form the underpinning of traditional religions like Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

You couldn’t find a better person to do the analysis than Epstein. He holds a master’s degree from the Harvard Divinity School, has been a humanist chaplain at Harvard University for more than 20 years, and served for a year-and-a-half as the Ethicist in Residence for TechCrunch, a popular website reporting on technology.

Epstein pursues his analysis with vigor, discipline, and a solid sense of history. He points out that, starting in the eighteenth century, Western society has been turning away from the belief that traditional religion has the best answer to humanity’s search for “meaning, purpose, and ethics.” Instead, he says, it has turned to technology and science “not just for solutions to specific problems like how to cross the Atlantic or defeat a harmful bacterium, but for solutions to the broader problems of being human.”

That leads him to tech today and the core of the book’s argument, that “tech possesses a theology, a set of moral messages, that dominate the way we think and feel…a doctrine, including concepts that have been core to the history of the world’s great religions up to now: heaven, hell, and afterlife.” Technology even has its own gods, he says, notably artificial intelligence. (His book is prescient about that. The New York Times recently reported, “On religious apps, tens of millions of people are confessing to spiritual chatbots their secrets.”)

He methodically analyzes all the structural ways in which tech meets the definition of what we think of as a traditional religion: Its rituals, hierarchies, apocalypses, congregations, apostates, and heretics. He doesn’t examine them in a purely dispassionate way, but instead with an eye towards the harm tech’s religion has done.

The chapter about hierarchies and castes is a particularly apt example. He points out that “tech’s hierarchies came to exist for similar reasons to those of religion: to make life easier for some by making it more difficult for others.” A look at the C-suite or boardroom of any tech company proves his point. White men are everywhere; anyone else is rarely seen. Epstein notes that more than 83% of tech executives are white and 80% are men, and that 93% of VC dollars are in the hands of white men. So, it’s no surprise that one section of his book calls tech “Utopia for white men.”

It wasn’t always this way, he reminds us. Before the PC revolution of the late 1970s and early 1980s, most coders were women, because coding jobs were seen as akin to secretarial work and paid accordingly. But once tech took off and tech multi-millionaires began to be minted, men took over coding jobs and were not just paid well but also lionized instead of devalued. Tech’s religion required it.

Although Epstein’s analysis and critique of what he calls a tech religion are on target, his solutions for undoing its damage are bland, vague, and toothless. He recommends we flatten tech companies’ hierarchies, without saying how that can be done. He suggests we turn away from our own focus on tech by concentrating on what our “positive and compassionate ideals and values require of us.” He urges us to “Be a human in a tech-first world.” I could list more of his bromides, but you get the point.

His ineffectual platitudes remind me of the movement in the Catholic Church in the 1960s that believed playing guitars at mass could be an important step towards reforming the church. But all the guitar-playing in the world didn’t make the church any less misogynist, didn’t stop it from fighting against birth control, against a woman’s right to have an abortion, against women being allowed to become priests. And the sweetest music played by the sweetest-sounding guitars didn’t stop the church from allowing its priests to rape children at will for decades, protect them from prosecution, and then cover it up.

Epstein’s solutions for reining in the tech industry’s avarice are just as feeble. Because tech isn’t a religion. It’s a hard-nosed business. And its excesses can only be reined in by strict government regulations and hard-charging prosecutors, not by milquetoast admonitions to be a human in a tech-first world.

Preston Gralla has won a Massachusetts Arts Council Fiction Fellowship and had his short stories published in a number of literary magazines, including Michigan Quarterly Review and Pangyrus. His journalism has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, USA Today, and Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, among others, and he’s published nearly 50 books of nonfiction which have been translated into 20 languages.

This review argues that Tech Agnostic accurately diagnoses how technology has assumed the trappings of religion—with commandments, rituals, apocalypses, and hierarchies—but criticizes its proposed remedies as vague, mild, and insufficient.

David: Yes, you’re right — the book is generally on target in the way it shows how we treat technology in ways that we traditionally treat religions. And as you say, the book’s remedies fall woefully short of solving the many problems technology creates.