Book Review: “The Art and Life of Francesca Alexander” — One of a Kind

By Kathleen Stone

An illuminating book about the 19th-century American artist Francesca Alexander, a Bostonian who shaped a very different life for herself and for her art.

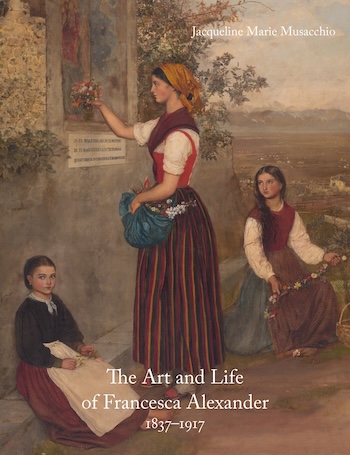

The Art and Life of Francesca Alexander: 1837-1917 by Jacqueline Marie Musacchio. Lund Humphries, 208 pages $44.99

Nineteenth century American artists, including a healthy dose of Bostonians, flocked to Italy to study art, absorb the culture, and widen their connections within the expat community. Upon their return to the U.S., many created highly acclaimed work. Thomas Ball’s equestrian sculpture of George Washington, for instance, stands at the Arlington Street entrance to the Public Garden. Martin Milmore’s Soldiers and Sailors Monument, commemorating Massachusetts fighters in the Civil War, graces a rise in the Boston Common. Celebrated painters Thomas Cole and John Singer Sargent are just two of the many who incorporated elements of Italian artistic legacy into their celebrated work. But one, Francesca Alexander, shaped a very different life for herself and for her art, as compellingly described in Jacqueline Marie Musacchio’s The Art and Life of Francesca Alexander, 1837-1917.

Nineteenth century American artists, including a healthy dose of Bostonians, flocked to Italy to study art, absorb the culture, and widen their connections within the expat community. Upon their return to the U.S., many created highly acclaimed work. Thomas Ball’s equestrian sculpture of George Washington, for instance, stands at the Arlington Street entrance to the Public Garden. Martin Milmore’s Soldiers and Sailors Monument, commemorating Massachusetts fighters in the Civil War, graces a rise in the Boston Common. Celebrated painters Thomas Cole and John Singer Sargent are just two of the many who incorporated elements of Italian artistic legacy into their celebrated work. But one, Francesca Alexander, shaped a very different life for herself and for her art, as compellingly described in Jacqueline Marie Musacchio’s The Art and Life of Francesca Alexander, 1837-1917.

Esther Frances Alexander, known as Fanny in her youth and later as Francesca, was born in Boston in 1837. Her father, an artist, spent two years as a young man in Italy doing what so many others did – studying ancient and Renaissance art, copying masterworks and mingling with other Americans. When he returned home, he exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum and private galleries, and painted portraits of elite Bostonians and visiting luminaries, such as Charles Dickens. The little girl Fanny was absorbed into this world and, with her father’s encouragement, developed her own interest in art. Among her earliest drawings were depictions of country woodlands, flowers, literary characters, and people who lived nearby. Notably, two of her portraits were of Black women who lived on Beacon Hill, part of that neighborhood’s free Black community.

When Fanny was 16, the family moved to Florence. Unlike many expats, they already knew some Italian words and soon all three were bilingual. They developed friendships with a wide range of Italians – writers, political activists, musicians, members of religious orders and noblewomen. Fanny’s gentle spirit and her interest in charity work caught the attention of adults around her, and many commented on those qualities. For her art, she added copies of Italian works to her repertoire.

One early work titled Charity, painted when Fanny was 24, shows a girl dressed in red and gold handing out food to barefooted children. Each girl is distinctive but, interestingly, none makes direct eye contact with another. Perhaps it was a first meeting and all were shy.

As she matured, Fanny’s attention to Italian life deepened and contadini, as peasants were called, became her friends and artistic subjects. If there was shyness in her earlier painting, there was none in her personal life. One contadina friend taught her popular songs and stories, and Fanny depicted her in paintings as a mother holding her baby, as a rustic woman in traditional dress and, in a religious moment, holding a rosary and a prayer book. She depicted another friend with a sickle and sheaves of wheat, evoking the Old Testament heroine Ruth. That friend, in another painting, is shown sewing in a comfortable room, probably one of Fanny’s friends who gathered at her residence to work on domestic tasks. In these, as in all Fanny’s portraits, the subjects look self-contained yet approachable, individuated by details such as the set of her eyes and the curvature of her mouth. Fanny honed her craft over a lifetime and aligned her art with her personal life in a unique way, often raising money for her peasant friends. Locally, she became known for her art and her charity. Friends back in Boston followed her progress and sought her out when they visited Florence.

Francesca Alexander, “Charity,” 1861, oil on canvas. Photo: courtesy of Sotheby’s Inc.

Beyond painting and drawing, she branched out into writing and music. One of her stories was about an Italian woman who died young after a life of hardship. She also created a folio of songs she learned from her Italian friends that included musical notation and her own illustrations.

When John Ruskin visited Florence in 1882, his final visit to that city, Francesca was given the opportunity to extend her reputation internationally. Ruskin was excited by her work, which accorded with his own interests in peasant life, religion, and naturalistic art. He asked for, and received, her permission to publish her book of songs and other writings in England, where his reputation would add luster to hers. In drumming up interest in one of the forthcoming publications, he described Francesca this way:

“. . . this American girl has lived – from her youth up, with her (now widowed) mother, who is as eagerly, and which is the chief matter, as sympathizingly benevolent as herself. The peculiar art gift of the younger lady is rooted in this sympathy, the gift of truest expression of feelings serene in their rightness; and a love of beauty – divided almost between the peasants and the flowers that live round Santa Maria del Fiore. . . She has thus drawn, in faithfullest portraiture of these peasant Florentines, the loveliness of the young and the majesty of the aged: she has listened to their legends, written down their sacred songs; and illustrated, with the sanctities of mortal life, their traditions of immortality.”

Being associated with Ruskin did indeed bolster Francesca’s reputation. After her work was published, ever more travelers sought her out, some just to watch her sketch or write. But other than trying to accommodate them, Francesca changed little about her life. Though she received almost no proceeds from Ruskin’s sales of her work, she continued to live comfortably on family funds and proceeds from direct painting sales. She also continued charitable work for her contadini friends. Her aging brought difficulties. She gradually lost her sight and was incapacitated by a bad fall. Her mother, with whom she lived, died at age 102, and Francesca died eight months later, at 79. Both were buried in a cemetery in Florence, next to their father and husband. Little publicity followed, and Francesca’s story has remained largely unknown until now.

Musacchio, a professor of art history at Wellesley College, brings a scholarly approach to telling Francesca’s story. Her research is deep and touches on artwork in small and private collections, as well as better-known holdings. Often, letters and journals are quoted, providing a perspective on the writer’s thoughts that otherwise would have been lost. Francesca lived most of her life in Italy, but because her family was well-connected in Boston and maintained their long-distance friendships, the book is peppered with well-known names, such as John Greenleaf Whittier, William Dean Howells, Lydia Maria Child, James Russell Lowell, Charles Bowditch and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Through them, we are given a picture of Bostonians of the time, including their European travels. We also get a glimpse into the Risorgimento, the 19th century political movement for Italian unification, with which Francesca and her family were in sympathy. It would have been interesting to read more about both the Italian political context and activities in Boston — to see how Francesca fit into her historical context. Essentially, though, she was one of a kind, both in her life and in her art, and followed her own heart, rather than the trends of the times.

Kathleen Stone is the author of They Called Us Girls: Stories of Female Ambition from Suffrage to Mad Men, an exploration of the lives and careers of women who defied narrow, gender-based expectations in the mid-20th century. Her website is kathleencstone.com.

Tagged: "The Art and Life of Francesca Alexander: 1837-1917", Francesca Alexander