Poetry Review: Askold Melnyczuk’s “The Venus of Odesa” — A Jukebox of One-Hit Wonders

By Michael Londra

Of special interest is Askold Melnyczuk’s treatment of objects. His imagination transforms curios into uncanny artefacts.

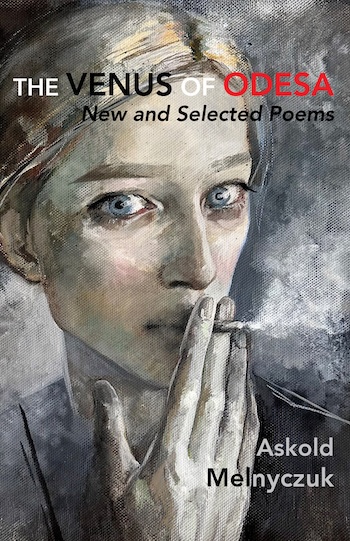

The Venus of Odesa: New and Selected Poems by Askold Melnyczuk. MadHat Press, 160pp. $21.95

Nobel laureate Derek Walcott once declared that “the fate of poetry is to fall in love with the world, in spite of History.” Akin to the Buddhist notion of “beginner’s mind,” Walcott encouraged literary artists to cultivate the “heart of an amateur,” and reject the “literature of recrimination and despair.” He called this activist method “Adamic.” He derived it from the biblical myth of Adam, who conjured the world of appearance into being by giving everything a name. In that way, Walcott sought to tap into the rejuvenating potential of visionary language. He used poetry to reassemble experience, twinning defiance with creativity. Confronting imperialism, atrocity, and ethnic identity erasure, Walcott renounced hopelessness. Opposed to cynicism—no matter how justified—Walcott defined his poetics as a counterweight to barbarity. Reveling in beauty, insisting on love’s capacity to transform the human heart from within, Walcott ceded no ground. In this sense, he seconded Bertolt Brecht’s 1939 poem “Motto.” Opposition to subjugation is sustained by the resilience of lyric utterance: “In the dark times, / will there also be singing? / Yes, there will also be singing. / About the dark times.”

This is also the stance of Askold Melnyczuk. Now seventy, Melnyczuk retains—despite dark times—the joie de vivre from his earliest writings. His debut poetry collection The Venus of Odesa: New and Selected Poems harvests stanzas from across the past half-century. In the opener, “Dance of the Tomahawks” (from The Village Voice in 1974), the themes animating his later work are present, though nascent: kinship, violence, gallows humor. A footnote explains that the Tomahawks were a “Brooklyn street gang active in the seventies.” Reminiscent of Walter Hill’s The Warriors, a movie exploiting the zeitgeist of that era (New York as “Fear City:” blackouts, abandoned buildings, and battles between outfits with names like Phantom Lords and Devil Rebels), Melnyczuk includes what Hill leaves out. Namely, the perspective of suffering (“The Tomahawks are pushing icepicks / Through my teeth”). As the Tomahawks’ leader prepares his violent coup de grậce, Melnyzcuk inverts his clichéd subject matter by infusing it with humanity: “Lying flat on this dark street / I watch the young chief…He is thinking of his mother / Whose hair he wears / Whose eyes he has.” Taking Walcott’s Adamic approach, he modifies the real: it is a process of rearrangement rooted in a radical sympathy that gestures at a burgeoning Buddhist sensibility: “We are brothers one / Soul continually searching / Each in his manner.”

In the best sense, The Venus of Odesa is a jukebox of one-hit wonders. An aesthetic nomad, Melnyzcuk does not privilege any single poetic style. Like a musician unwilling to repeat himself, these pages consist of discrete pieces that formally stand independent from each other. Yet, while each iteration finds its own configuration—metered quatrains jostle elbows with free verse and a prose poem—Melnyzcuk’s obsessions evolve but stay fixed. In childhood, his love of literature starts as a kid’s desire for attention (“I stand / on a dining-room table / like a lamp reciting / syllables of unbroken light // by a poet a century gone,” from “Forsythia”). As an adult, it morphs into a bulwark against political oppression (“tonight I’ll read poems / by Rudenko, who is in prison / for speaking out for the beaten,” from “The Way of the World”). First generation American, Melnyzcuk eulogizes the immigrant experience of his parents and grandparents (“He survived. / They survived…Made their way / out of the ghetto // into the burbs. / Children, money, sunflowers,” from “The Voyagers”). But assimilation is not a crystal stair. Especially given that Melnyzcuk is taught Ukrainian at home, instead of English, before attending kindergarten (“I think serce moyeh / but what I say / my pen won’t put / to paper in // this hostile tongue,” from “The Mouth Refuses to Translate”).

Despite that rough start, he would go on to do well in school, eventually becoming a professor of creative writing at UMass-Boston. These poems reflect Melnyzcuk’s erudition. References include Rilke, Descartes, Julius Caesar, Ukrainian graphic artist Edward Kozak, Catullus, Plato, Maud Gonne, Paul Celan, La Bohème, Goya, Alexis de Tocqueville, Liv Ullmann, among others. And, of course, The Venus of Odesa also elegizes the torments of failed love (“Oh troubled heart, beset…with volumes of regrets,” from “Geese in Winter, Medford”). However, that changes when he marries and engages with Buddhist texts of enlightenment that expand his consciousness, like The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

In fact, more than exhibiting any particular feature of a precursor poet (such as Robert Lowell’s formal rhetorical style on Derek Walcott’s early syntactical approach), Melnyczuk’s verses are instead acutely influenced by Buddhism’s four sublime states—kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. Buddhism’s impartial benevolence and generosity of spirit pervades lines such as these, demonstrating empathic understanding and fellow feeling for a stray cat: “Knowing by hurt what happens / when a creature crosses a road // at just the wrong moment” (“Alley Cat”). This profound concern even extends to the life of a moth: “I took out / a thermos and poured a cup of coffee. A moth fell in / and it was too late to save it” (“All Talk is Moths”).

Melnyzcuk’s father was perhaps his first Buddhist teacher: “My father dying, said: / I never willed / harm on a single soul” (“Geese in Winter, Medford”). This bond between them runs deep. So much so, Melnyzcuk is not disturbed by his father’s end-of-life hallucinations. He accepts his father’s impossible truth as real: “A cathedral rose / In a pint of yoghurt / You were spooning…It wasn’t the morphine. / You were dying of pain. You saw / What you saw” (“My Father Has a Vision”).

Of special interest is Melnyzcuk’s treatment of objects. His imagination transforms curios into uncanny artefacts. For example, The Venus of Odesa is a title derived from a clay figurine—the Polovtsian “Baba”—housed in the Odesa Archeological Museum. Melnyzcuk explains that it is a Ukrainian “pagan burial figure” that reminds him of “the Venus of Willendorf.” This association sparks his imagination to rechristen the statuette “Venus of Odesa.” Echoing Freud, Melnyczuk intuits that one person’s junk is another’s talisman. It’s all in how you use your eyes. Melnyzuck’s powers of perception can transform a lifetime’s detritus: “Suddenly the crap has meaning: / old wallets, scarves, the radio…batteries, blue shirt…sweaters, the scarred belts…Apocatastasis of objects” (“A Potato Reading Rilke”).

Among his poems in this regard, “The Enamel Box,” stands out. Born in New Jersey to émigré parents fleeing communist persecution, a “trinket” has been gifted by a “visitor from Ukraine.” This tchotchke triggers a fantasy. Melnyzcuk time-travels to the old country. It feels like his origin story: “I imagine / a mother, father, a child, a house: / external actors, paramours of joy and pain, / except the child, born all eyes, / who sits at the window.” Here it is: staring at the world became a conduit to a poetic personality. Appropriately, The Venus of Odesa’s cover image is an atmospheric self-portrait by Ukrainian artist Ksenia Datsiuk. Dragging on a cigarette—yellow hair pulled back—her self-possessed blue-gray eyes predominate. Datsiuk’s visage is very much “all eyes.”

In that vein, every poet is indeed “born all eyes”—an eyewitness. Carolyn Forché pioneered this notion in her anthologies Against Forgetting: Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness and Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English, 1500-2001(co-edited with Duncan Wu). Moreover, The Venus of Odesa epitomizes what Seamus Heaney called, in The Government of the Tongue, “radical witness.” Heaney believed the “truth-telling urge and the compulsion to identify with the oppressed becomes necessarily integral with the act of writing itself.”

Askold Melnyczuk — Now seventy, he retains—despite dark times—the joie de vivre from his earliest writings. Photo: Arrowsmith Press

Still, Melnyczuk remains troubled. Occasionally bitterness and disillusion overflows into self-loathing: “Once I would have done anything for you, / Poetry. Now….I say: fuck the work.” (“The Cost of Nothing”). To combat such self-indulgence, Melnyzcuk draws on caustic humor. This is especially apparent in “The Voyagers,” a comic tale of Melnyczuk’s grandfather losing his teeth in the Atlantic while he was escaping communism: “On the boat coming over…When his dentures / dropped out, / his wife screamed: / ‘Part of man // overboard.’ ” Utilizing irony to mock pretense, his snarky quips resonate with wit and wisdom: “There’s a con / In all concepts” (“In the Arms of the World”). Memorably updating Homer’s Odysseus in sitcom terms, “The Odyssey, Revised, Standard” is SNL-meets-David Sedaris. At other times, however, Melnyzcuk’s sardonic sting feels adolescent. Out of character with the rest of the volume, “Buddhist Diary 1954-2024” is a joke that falls flat—other than the title, the page is blank. Perhaps Melnyczuk articulates the Buddhist doctrine of no-self. The punchline is too on the nose.

Given Melnyczuk’s love of Ukraine, it’s no surprise he has introduced Ukrainian writers to Anglophone audiences. In the wake of Putin’s genocidal war, Melnyczuk’s translations in The Venus of Odesa take on greater import. Notably, five poems by Taras Shevchenko. Progenitor of modern Ukraine, poet and painter Shevchenko (1814-1861) was an instrumental figure who, à la Walcott, dreamed Ukraine’s national character into existence with his poems.

Adjusting your focus from what is to what isn’t seen is Buddhism par excellence. Following the Tibetan school, Melnyczuk groks the invisible soul is luminous: “the self walking alone / is a vulnerable radiance” (“After Snowfall”). Mortality is an incomplete endeavor: “Since you are a mental body / you cannot die…You / are…emptiness…there is no need to fear” (“Late”). Ditto for love: “a life-/ long, death- / long conversation” (“The Venus of Odesa”). What’s in him is in everything: “Admit to the stones they know / more than you, and are you” (“Melancholy Baby”).

The Venus of Odesa’s final poem is “Verses from Shantideva.” Referencing an 8th century Buddhist monk, Melnyzcuk brings it all back home: “We dwell / In the presence of / The Buddhas and Bodhisattvas / who see all.” Thus, it’s not just Melnyczuk who was “born all eyes.” Buddha and Adamic poets strive to expand acuity, to reconstitute experience from scratch. Melnyzcuk’s concluding lines convey this universality. Walcott would approve: “Give up frowning and anger. / Smile. / Be a friend and counsel to the world.”

Michael Londra talks New York writers in the YouTube indie doc Only the Dead Know Brooklyn (dir. Barbara Glasser, 2022). “Time is the Fire,” the prologue to his forthcoming Delmore&Lou: A Novel of Delmore Schwartz and Lou Reed is published in DarkWinter Literary Magazine. Other fiction, reviews, and poetry have appeared or soon will in Restless Messengers, Asian Review of Books, The Fortnightly Review, spoKe, The Blue Mountain Review, and Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, among others. He contributed the introduction and six essays to New Studies in Delmore Schwartz, out next year from MadHat Press. He lives in Manhattan.

Tagged: "The Venus of Odesa: New and Selected Poems", Askold Melnyczuk