Book Review: “Three Speeches That Saved the Union” — Truth, Powerful and Strange

By Tom Connolly

The political and moral consequences of the Compromise of 1850 continue to be debated, but Peter Charles Hoffer’s book offers valuable lessons on how concession and consensus once served as pillars of the Republic.

Three Speeches That Saved the Union: Clay, Calhoun, Webster, and the Crisis of 1850 by Peter Charles Hoffer. NYU Press, 248 pages, $32

Among the many betrayals of the sacred principles upon which our nation was founded, particularly those that afflict us today, is the casualness with which sectors of the left and right toss about the idea of secession, or even another civil war. A term such as “a great divorce” is used to describe the “inevitable” dissolution of the Union into red and blue states, or “soft secession” is urged upon the blue states (particularly galling because the “blue” states are the ones that fought to save the Union). Recently, President Trump’s wish that Canada will become the 51st state has inspired some Americans to want to become Canadians. The irony is breathtaking: 250 years after the Battle of Bunker Hill, some of our fellow citizens are eager to become subjects of the British Crown again.

Among the many betrayals of the sacred principles upon which our nation was founded, particularly those that afflict us today, is the casualness with which sectors of the left and right toss about the idea of secession, or even another civil war. A term such as “a great divorce” is used to describe the “inevitable” dissolution of the Union into red and blue states, or “soft secession” is urged upon the blue states (particularly galling because the “blue” states are the ones that fought to save the Union). Recently, President Trump’s wish that Canada will become the 51st state has inspired some Americans to want to become Canadians. The irony is breathtaking: 250 years after the Battle of Bunker Hill, some of our fellow citizens are eager to become subjects of the British Crown again.

In her newsletter, “Letters From an American,” historian Heather Cox Richardson frequently examines the historical legacy of Trumpism, tracing it to the white supremacist, antidemocratic legacy of slavery’s proponents. The contradictions inherent in the states’ rights argument, used to assert the legal basis of slavery, eluded then proponent John C. Calhoun, as it escapes the Heritage Foundation’s notice today in Project 2025. The notion is that the Federal government must enforce the will of the minority, whether that means enforcing the “rights” of slave owners then or ignoring legal precedent and the rule of law itself now.

Peter Charles Hoffer’s richly detailed and closely argued analysis of the three Senate speeches that secured the Compromise of 1850 transports us back to a time when oratory, not the 30-second sound bite, ruled. The rumor that Daniel Webster would address the Senate packed its galleries and every available space on its floor. The complexity of the legislative wrangling that led to the Compromise carries on in its historical legacy. Yes, it saved the Union; it delayed the Civil War by 10 years. Was this worth it? Was the Union’s preservation worth the horror of the Fugitive Slave Law and a decade of capturing enslaved people who managed to escape or hunting down freed men and women?

Often overlooked is that the Compromise did not create the Fugitive Slave Law — it only strengthened it. The upshot of the latter is that hundreds of enslaved people were dragged back into bondage. But it also galvanized the abolitionist movement, and thousands escaped captivity, led by Harriet Tubman and others along the invigorated Underground Railroad. Bostonians who had silently abhorred slavery were confronted by the sight of men and women in chains being led down State Street to Long Wharf. That galvanized active intervention. Daniel Webster, formerly known as “godlike Daniel,” was pilloried as “Ichabod” in a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier for his support of the Compromise and insistence that the Fugitive Slave Law must be obeyed:

So fallen! so lost! the light withdrawn

Which once he wore!

The glory from his gray hairs gone

Forevermore!

The other two senators who led the fight for the Compromise, Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, died shortly after it was approved. Webster lived long enough to be vilified but, on the eve of his death, there was a triumphant reconciliation with his constituents. I would argue that an unintended consequence of Webster’s dubious battle for the Compromise was that his idea of the Union was solidified in the minds of Northerners. This ideal would inspire them to fight and die 10 years after Webster breathed his last. The “Minutemen of ’61” had recited, since grade school, Webster’s ringing conclusion to his Second Reply to Hayne: “Liberty and Union now and forever, one and inseparable!”

The divisions bedeviling Americans today are shoals compared to the gulf of 1850. Westward expansion forced the issue of slavery’s expansion. Rather than withering away as the Founders had hoped, it burgeoned and, by 1850, Calhoun and his proslavery cohorts horrifically hailed it as an economic boon and a ribbon of honor to be pinned on the chest of the South.

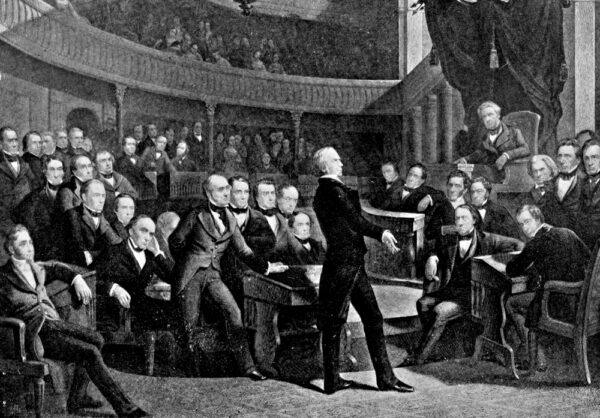

A 1900 illustration depicts the US Senate in 1850, as Senator Henry Clay delivers a speech. Seated in the second row behind him is Daniel Webster, and on the far right is John Calhoun. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Hoffer notes that Calhoun’s admonitory speech promoting the Compromise was prophetic; the South would take up arms to defend slavery. Calhoun’s words threatened. Clay spoke for the West and the “Great Compromiser” achieved his final victory. The speech of the latter set out to ameliorate. Webster was the voice of the North — opposing slavery, but fundamentally committed to binding the Union. Webster invoked the sanctity of the Republic.

Almost absent from the all-important debate: President Millard Fillmore. A sign of the gulf between the mid-19th century’s aegis of congressional authority and today’s imperial presidency. The political and moral consequences of the Compromise of 1850 will continue to be debated, but Hoffer’s book offers valuable lessons on how concession and consensus were once pillars of the Republic.

Tom Connolly is Professor Emeritus of of Humanities and Social Sciences at Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University. He recently edited a historical study (in English) of the 19th- and 20th-century Jewish community of Döbling for the Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Institut für Kulturwissenschaften. His book Goodbye, Good Ol’ USA. What America Lost in World War II: The Movies, The Home Front and Postwar Culture is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin/PMU Press.

Tagged: "Three Speeches that Saved the Union", Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun