Book Review: Risk, Rebellion, and Regret — Larry Charles Tells All in “Comedy Samurai”

By Gerald Peary

Larry Charles is by every standard a seminal figure in contemporary humor, on the tube and in movie theaters. Why doesn’t everyone know his name?

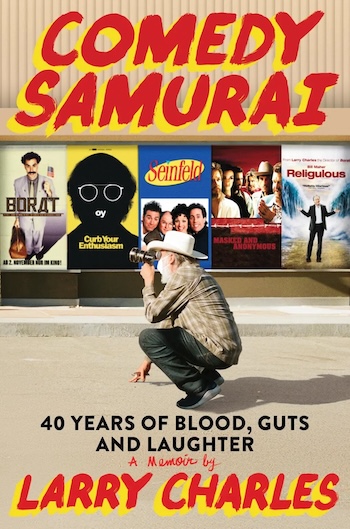

Comedy Samurai: 40 Years of Blood, Guts, and Laughter by Larry Charles. Hachette Book Group, 400 pages, $32.50

A lucky break for Larry Charles. In 1978, he was hired at 22 to write for an LA-based TV answer to Saturday Night Live called Fridays. Among the other writers was a guy from his Brooklyn neighborhood, Larry David, ten years older. David befriended him and, a few years later, hired Charles as a staff writer for Seinfeld. He brought on Charles a second time as a director-producer for Curb Your Enthusiasm. Among the guests on Fridays was Andy Kaufman. Kaufman’s fervent commitment to the most bizarre of characters, his uprooting and trashing of conventional comedy, his toying in his routines with physical danger, all affected Larry Charles for a lifetime.

A lucky break for Larry Charles. In 1978, he was hired at 22 to write for an LA-based TV answer to Saturday Night Live called Fridays. Among the other writers was a guy from his Brooklyn neighborhood, Larry David, ten years older. David befriended him and, a few years later, hired Charles as a staff writer for Seinfeld. He brought on Charles a second time as a director-producer for Curb Your Enthusiasm. Among the guests on Fridays was Andy Kaufman. Kaufman’s fervent commitment to the most bizarre of characters, his uprooting and trashing of conventional comedy, his toying in his routines with physical danger, all affected Larry Charles for a lifetime.

Push the limits, push the limits more, absolutely anything goes, the more lunatic the better, the more you alienate the better, even if your cast and crew could be physically harmed, that became Charles’s credo when directing perhaps the two funniest comedies of our new century, Borat (2006) and Bruno (2009). More insolence: with self-proclaimed atheist Bill Maher, Charles made a smarmy satiric attack on believers of every faith in the proudly secular Religulous (2008).

Add in Charles’ stellar work as the showrunner for the anarchic cable-TV testosterone explosion, Entourage, and his inspired stint, also as showrunner, moving what he calls the “feather witty romanticism” of NBC’s Mad About You into a deeper comedy of adultery, marital separation, and breakdown. Larry Charles is by every standard a seminal figure in contemporary humor, on the tube and in movie theaters. Why doesn’t everyone know his name? Is it because he’s been such a weirdo in an increasingly corporate Hollywood world, often dressing, he admits, like a homeless person, coming to work in pajamas and with the long beard of a rifle-toting hillbilly?

The hell if I know. But maybe his fame will increase with the publication of his lively and witty memoir, Comedy Samurai: 40 Years of Blood, Guts, and Laughter.

But hold the praise a minute. A fine book, but why doesn’t Charles offer some chapters about his Brooklyn childhood and the move of his Jewish parents to Florida? I wanted to know far more about his elusive father, who at some point got sick of being a parent and turned into an obsessive adulterer. This dad is a haunting figure. Unhappily, Charles would realize that he, the son, carried over this tainted legacy in his own shaky marital life.

Selfish me: I wanted to hear about Charles attending Livingston College, Rutgers University. That’s where, I learned in an email a few years ago, that he once took a class called “Hardboiled Films and Fiction” co-taught by yours truly. I have no memory of young Larry as a student in the mid-’70s, but he told me that my course was a big influence on his directing of Seinfeld. Was he bullshitting me? Sure enough, he speaks in his book of his “film noir”-driven Seinfeld episodes. Alas, there’s no mention therein of the humble academic behind it all!

I forgive thee, my ex-collegiate. And back to the book. Seinfeld was so unique because it was conceived, Charles says, by a bunch of people who hardly ever watched sitcoms, whose comic references more likely came from the movies, things like Abbott and Costello and The Three Stooges. (Additionally for Charles, Andy Kaufman and Lenny Bruce.) There was no writers room, so ideas floated about freely and informally. Fridays had been a cocaine zone. For Seinfeld, it wasn’t drugs, though unhealthy activities squeezed into the production schedule: Charles and Larry David became hooked gambling on football games, Charles and Jerry Seinfeld did perilous two-car drag races through the streets of Los Angeles.

Even though the TV series was a smash hit, NBC was all over Seinfeld trying to tone it down, even censoring programs that were “deemed too dark and brash and unsettling.” As an example, there was a dandy episode planned in which Elaine gets on the wrong express train and finds herself the only white person in the subway car at 125th Street Harlem. That was a no-go for the network. However innovative Seinfeld was, however the scripts were sprinkled with delectable “meta moments,” the program was ultimately too sedate for Charles, surely the wildest-thinking of its team of writers. He resigned to move onto other challenging projects.

Larry Charles — he directed what might be the two funniest comedies of our new century. Photo: Netflix

Like collaborating with the impossibly challenging Bob Dylan.

More luck for Larry Charles. He never knew it before, but he turned out to be the cousin of Dylan’s manager Jeff Rosen. They met, they bonded over the web of dysfunction in their Jewish Florida family tree. So who but Charles would be a natural to write and direct for Rosen’s royalty client? Apparently Dylan decided one day, after laughing through a bevy of Jerry Lewis movies, that he was ready to star in a TV sit-com series. What a dizzy, uproarious chapter in Comedy Samurai when Dylan and Charles come together for 12-hour powwows, Dylan chain-smoking in a tiny office behind an LA boxing arena. The climax was a meeting with HBO in which Charles pitched the series while Dylan sat quietly, passively, and it ended agreeably with the star-struck HBO executives greenlighting everything. Until Dylan in the elevator going down declared, “I don’t want to do it anymore,” labeling his foray into TV “too slapsticky.”

But there was more Bob Dylan for Larry Charles. Under pseudonyms, Rene Fontaine and Sergei Petrov, they were co-writers of a 2003 hippy sci-fi quasi-musical film called Masked and Anonymous, aptly described by Wikipedia: “An iconic rock legend, Jack Fate, is bailed out of prison to perform a one-man benefit concert for a decaying future North American society.” Dylan starred as Fate, and Charles directed. I love this story: on the set, Charles pleaded with his fickle, anti-social lead to please say “Hi!” to the cast and crew when he walked past them. I don’t think Dylan obeyed. Masked and Anonymous was released, a box-office flop, and panned by most critics as being formless, senseless, and indulgent. I gave the film one of its fairly respectful reviews, which was when Charles contacted me by email.

Anyway, that was it for Charles and Dylan working together or ever meeting again. Yet Charles is adamant in Comedy Samurai that he relished their time as a combo and has no regrets. Charles absorbed from Dylan an essential life lesson: Don’t look back. These are my favorite lines in Charles’ book: “So when people ask me if I’m still friends with Bob my answer is always, Bob has no friends but I amused him for a short time.”

I do believe it’s harder to write colorfully about toiling on a TV show than about employment on a movie. Charles’ chapters about Curb Your Enthusiasm are pretty perfunctory. And even thinking back to the Seinfeld chapters, I realize there’s an elephant in the room — how reticent Charles is about Jerry Seinfeld himself. He does note that Seinfeld and Larry David had some bitter disagreements, mentioning “Larry’s rising animus toward Jerry.” But what was that about? I’ll confess my private agenda: Several years ago, my wife and I paid more than $500 dollars between us to see Jerry in Boston doing stand-up. The show was a total rip-off with the so-called genius comedian reduced to the laziest, most bland and toothless jokes. So I wanted Larry Charles to lay into him! (It’s my intuition that Charles might share my disdain for the great Jerry Seinfeld. Am I right, Larry?)

Sacha Baron Cohen in Borat.

There’s no holding back about Sacha Baron Cohen in the multiple chapters concerning the star of Borat, Bruno, and the unfortunate follow-up The Dictator, all helmed by Charles. It’s the self-imploding saga of an actor of brilliance who Charles feels matched the heights of Brando and Olivier with his intense performances in Borat and Bruno. For these films, Cohen stayed immersed in his oddball roles for impossibly difficult 14-hour days. However, Charles witnessed Cohen becoming progressively meaner and more anti-social, transforming through the three films into a demanding control freak and megalomaniac. By the time of The Dictator, Cohen had acquired an entourage of “Yes” people, was hanging out with Hollywood’s “A” list, and barely remembered his lines or bothered to get into character. He arbitrarily fired crew, and he subverted Charles’s direction every which way.

But there had been earlier better times. It’s too in-the-weeds to detail them here, but Charles has eye-popping story after story of the treacherous situations that Cohen put himself into as Borat and Bruno always with Charles’s approval, i.e., when the Bruno crew were almost stoned to death as Cohen’s gay and swishy dandy sashayed in Hasidic-style hot pants through an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Jerusalem.

Charles says that these were emphatically not “director’s chair” movies. Most of the time, the filmmaker was crouching down, hidden in a corner, so that Borat’s and Bruno’s real-life victims would not notice that they were being filmed. And when threats came from enraged crowds and pissed-off police? “…I don’t fear as much for my safety, though perhaps I should. My primary concern is that the tapes are safe. I made sure I had possession of them as the mob and the police descended upon me.”

Brave on the job but — Charles writes about it with deep regret — cowardly in his personal life. He followed a trajectory of countless male artists: marriage and a flock of children then estrangement and long absences from home because of an obsession with work; then serial adultery but emptiness inside, ultimately the guts to divorce and a final marriage of safety and stability. Charles’s book dedication: “To my wife/rock Keely. It is not hyperbole to say I wouldn’t be here without her.”

A scene from Larry Charles’ Dicks: the Musical. Photo: A24

Charles’ career since 2010 has been downsized from the flourishing comedic years before. He had one very promising film, Army of One (2016), taken over, recut, and ruined by producer Bob Weinstein, Harvey’s almost equally evil and more philistine brother. He had another interesting project, a film based on Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods, taken away from him by its ever-cautious, up-tight star Robert Redford. Even Larry David turned on him, disallowing a long and revealing interview conducted by Charles from being shown on HBO. In his book, Charles is pretty sanguine about the situation: he and David no longer communicate, the same as with Cohen and Dylan.

Recently there was a wacky but not-quite-working indie feature, Dicks: the Musical (2023). But cheers for a spirited, heartfelt return to the top: a first-rate Netflix series, Larry Charles’ Dangerous World of Comedy, in which the filmmaker traveled to the most perilous countries on earth, in Africa and Asia, to meet with extraordinarily courageous, politically active local comedians. Charles, I believe, channeled Borat and Bruno in his on-camera hosting of this ever-dangerous series. “My fear drives me,” Charles, now 68, says on the last page of Comedy Samurai. “My hunger and desire drive me…I am the joker who desperately wants to believe life is not a joke… I live by a code. Or try to.”

By his own estimate, has Larry Charles made good on earth? He answers the philosophical question by referencing Some Like It Hot. Charles’s final words of his memoir are the famous concluding line of Billy Wilder: “Nobody’s perfect.”

Gerald Peary is a professor emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His last documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, played at film festivals around the world, and is available for free on YouTube. His latest book, Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, was published by the University Press of Kentucky. With Amy Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Tagged: "Comedy Samurai", "Curb Your Enthusiasm", "Larry Charles’ Dangerous World of Comedy", "Masked and Anonymous", "Seinfeld", Bob-Dylan