Classical Album Review: Anna Clyne’s “Abstractions”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

That composer Anna Clyne is a gifted miniaturist is evident in Abstractions, a set of five movements offering musical commentary on the works of five contemporary visual artists.

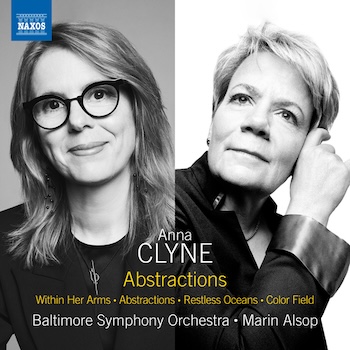

Anna Clyne is a composer with well-placed champions, both in the concert hall and the recording studio. Abstractions, her new release featuring the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and Marin Alsop, features three substantial numbers (two of them in their premiere recordings) and an engaging curtain-raiser. Running just 53 minutes, the album is a bit on the short side, though its brevity — nine of its 10 tracks last between just under three and just less than seven minutes — means that revisiting individual items is a cinch. In this fare, doing so is well worth the effort.

Anna Clyne is a composer with well-placed champions, both in the concert hall and the recording studio. Abstractions, her new release featuring the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and Marin Alsop, features three substantial numbers (two of them in their premiere recordings) and an engaging curtain-raiser. Running just 53 minutes, the album is a bit on the short side, though its brevity — nine of its 10 tracks last between just under three and just less than seven minutes — means that revisiting individual items is a cinch. In this fare, doing so is well worth the effort.

That Clyne is a gifted miniaturist is evident in Abstractions, a set of five movements offering musical commentary on the works of five contemporary visual artists. “Marble Moon,” after Sara VanDerBeek’s series of digital prints, provides an enchanting play of color and harmony, treating the orchestra like a giant organ (or is it an accordion?) along the way. The swashbuckling “Auguries” references Julie Mehretu’s eponymous etchings, while “Seascape” nods to Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Caribbean Sea, Jamaica and delivers an aura of delicate mystery — partly by way of a series of discrete dialogues between harp and piano.

The penultimate “River” (after panels by Ellsworth Kelly) is more vigorous; its coda is meant to suggest Tibetan singing bowls but also hints back at the haunting textures of “Marble Moon.” Philip Glass-like arpeggios morph into a subtle, alluring dance in the concluding “Three,” which takes its lead from Brice Marden’s painting 3.

Light and shadow also play decisive roles in Color Fields, which takes some of its inspiration from Mark Rothko’s 1961 Orange, Red, Yellow series. Here, too, Clyne traffics in slightly larger forms, though the results aren’t always so striking as those in Abstractions.

The main issue, such as it is, relates to repetition of gesture and harmony. To wit, parts of the opening two movements feel static. This is most pronounced in the second, “Red,” where iterations of rising, canonic figures sans modulation give the sense of spinning wheels.

True, part of Clyne’s aim in the music is to explore the phenomenon of synesthesia and orbiting around a D pitch-center — her chosen tonal area for that section pace Alexander Scriabin — accomplishes the goal. But the materials don’t quite support the mission. Rather, one is left wondering what more the composer might have accomplished had she not been hemmed in by these particular parameters.

And one needn’t wait long to find out: the finale, “Orange,” is, if anything, too short. But its shimmering, Holst-like textures and flexible allusions to previous movements are utterly entrancing. I’d love to hear Clyne spin this single movement into, say, a 20-minute canvas of its own.

After all, she’s perfectly adept in affecting, longform essays, as Within Her Arms, a tender memorial to the composer’s mother, attests. Something of a cross of Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen, Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, and Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Tallis Fantasia, it’s a beautiful threnody whose rhythmic and textural profile ebbs and flows with the unpredictability of grief — or waves lapping the shore.

The short Restless Ocean, on the other hand, is pulsing and seething. Its melodic writing boasts a vaguely Medieval quality, recollecting after a fashion Clyne’s woozy Masquerade. But the foot stomps, shouts, and orchestral singing that permeate the score locate it firmly in the present.

Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony deliver a rightly feisty account of the latter and knowing, fluent performances of the rest. One might quibble about a few little things — parts of Color Field would benefit from stronger contrasts of tone and dynamic range, the woodwind humming in Restless Ocean gets a bit lost in the mix — but all involved have Clyne’s style firmly in hand and mind. Together it makes for a fine release, one that’s accessible in all the right ways and should be of absorbing musical interest to newcomers and aficionados alike.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Anna Clyne, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Marin-Alsop